Scientist of the Day - Giuseppe Cocconi

Giuseppe Cocconi, an Italian physicist, was born in 1914, in Como. He studied physics in Milan, and then was invited to come to Rome to join a small group that included Enrico Fermi, where Cocconi became interested in cosmic rays, and constructed a cloud-chamber particle detector for Fermi. His studies were derailed by the War, but in 1947, he was invited by Hans Bethe to come to Cornell University and pursue his cosmic ray research there (and in the Rockies). He accepted, and ended up spending 15 years at Cornell, before moving on to CERN, the international physics laboratory in Geneva. Eventually he would become Director of Research at CERN and make many important contributions to cosmic ray studies.

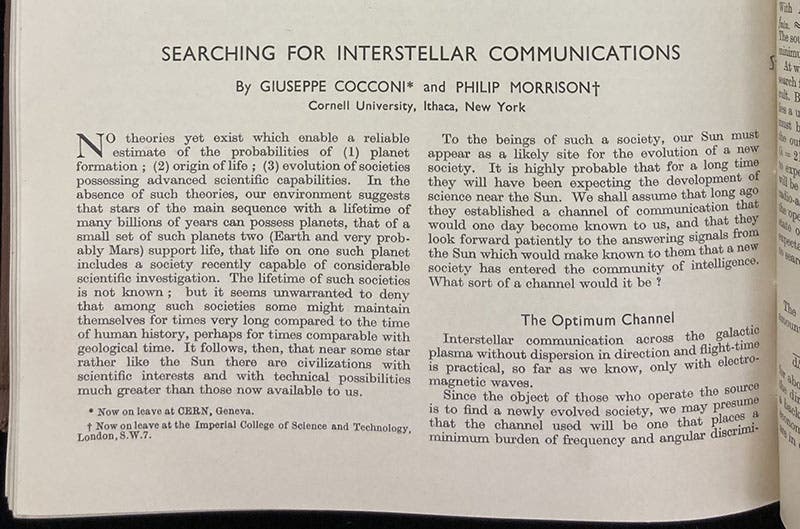

But Cocconi is best known for a short paper published in Nature on today's date, Sep. l9, 1959, that he co-wrote with Philip Morrison, a physicist from the Manhattan Project whom Bethe also invited to Cornell after the War. The paper was called "Searching for interstellar communications," and it constituted a first attack on a considerable problem: how do we go about looking for extraterrestrial life, especially intelligent life? Humankind had been in the radio age for just over 50 years, so it seemed natural to assume that extraterrestrials, at least the advanced ones, would have radio as well, and might use it to communicate. But radio receivers must be tuned to specific frequencies, of which there are an almost infinite number. So at what frequencies should we listen?

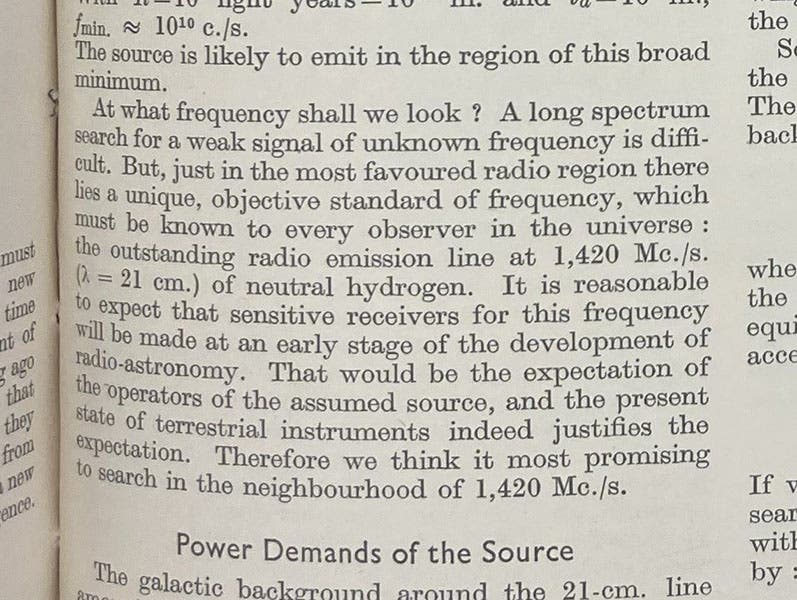

Cocconi and Morrison considered the problem, and concluded that extraterrestrials would probably communicate at a frequency that other civilizations might be monitoring for other reasons. The most logical communications frequency would be that at which interstellar hydrogen radiates, which happens to be 1420 megacycles (MHz in modern units). Every frequency in the electromagnetic spectrum corresponds to a wavelength, and for 1420 MHz, that wavelength is 21 cm. Since that is much easier to say, and forms a tidier mental image, Cocconi and Morrison concluded in their paper that we should tune our radio telescopes to the 21-cm band, and see if anyone is talking.

Paragraph on second page of “Searching for interstellar communications,” by Giuseppe Cocconi and Philip Morrison, suggesting that the search for radio waves should begin at the emitting frequency of neutral hydrogen, 1420 MHz, corresponding to a wavelength of 21 cm, Nature, vol. 184, p. 845, Sep. 19, 1959 (Linda Hall Library)

At the time their paper was published, there were very few operating radio telescopes in the world, but one of them was in Green Bank, West Virginia, where Frank Drake had already started a secret search for extraterrestrial intelligence, with a program called Project Ozma. He had figured out the 21-cm target band himself (that was the whole idea – it should be any smart person’s first choice for sending and for searching), but Drake wasn’t going to tell anyone about his work, since searching for ET was tantamount to professional death for an astronomer in those days. When Cocconi and Morrison let the whole world know about the 21-cm band, Drake went public as well, and organized a conference at Green Bank in 1961 – the world’s first SETI conference – that we discussed in our post on Drake. Both Cocconi and Morrison were invited; Cocconi declined, and Morrison attended. SETI was underway. And the official sanction was a paper in Nature, the most respected science journal in the world

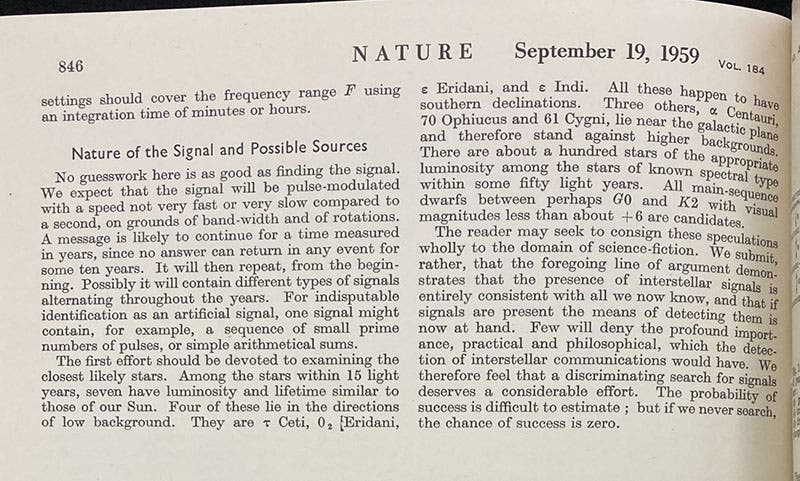

Last paragraph of “Searching for interstellar communications,” by Giuseppe Cocconi and Philip Morrison, where they conclude by saying: “The probability of success is difficult to estimate; but if we never search, the chance of success is zero,” in Nature, vol. 184, p. 846, Sep. 19, 1959 (Linda Hall Library)

The Cocconi-Morrison paper is discussed in every study of the origins of SETI, but I have never seen any part of that paper reproduced as accompanying illustrations. So we include three here; the opening paragraph (third image); the paragraph on the second page that proposes the 21-cm band as the best target for a radio search (fourth image); and the final paragraph, which concludes with a sentence often repeated: “The probability of success is difficult to estimate; but if we never search, the chance of success is zero” (fifth image).

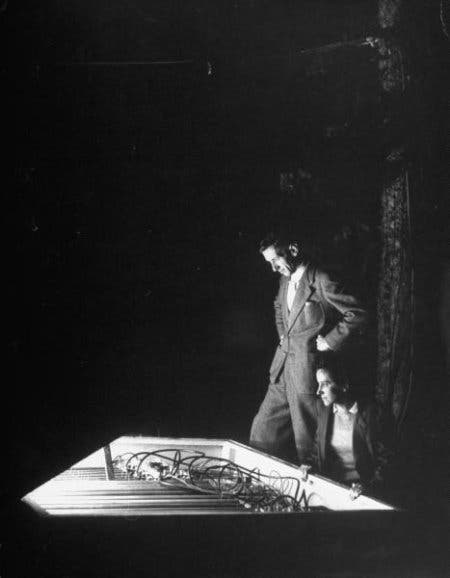

Cocconi was a fairly private person (which is why, I suppose, he declined Drake’s invitation to West Virginia), and not eager, apparently, to pose for photographs, so there aren’t many, especially of him in 1959. The one we open with was taken much later and survives only in a low-resolution format. But I do like the photo of Giuseppe and his wife Vanna, also an astrophysicist, inspecting some cosmic ray detectors, and taken before the 21-cm paper was published (sixth image). It does not provide much detail. But it does show style.

Cocconi died on Nov. 9, 2008, at the age of 94. If there is a gravesite, it has not been publicly revealed.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.