Scientist of the Day - Girolamo Cardano

Girolamo Cardano, an Italian physician, astrologer, and autobiographer, died Sept. 21, 1576, just shy of his 75th birthday. We wrote a post 7 years ago on Cardano, where we discussed his extraordinarily colorful life, and focused on a book, Libri quinque, the Five Books, a compendium on astrology that included 100 horoscopes of a variety of figures from antiquity to his present day. We showed the genitures (horoscopes for the moment of birth) of Albrecht Dürer, Johannes Regiomontanus, and Andreas Vesalius, without attempting to explain how the genitures were to be read and interpreted, since that is far outside of whatever spheres of expertise I have.

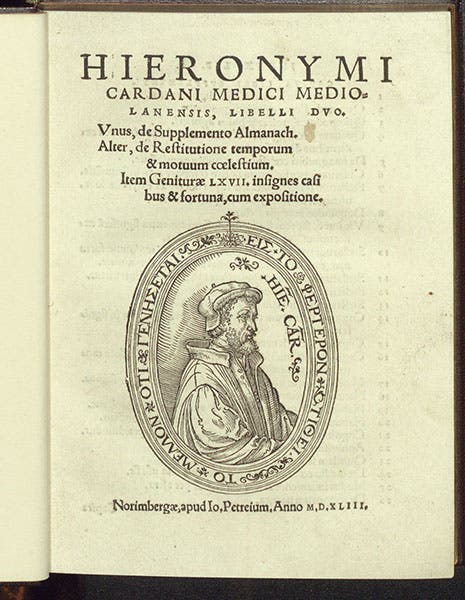

Today we are going to enrich the story, or try to, by introducing another of Cardano's books on astrology, which was actually published first, in 1543, and was called Libelli duo – the Two Books. We have a handsome copy in our collections. This volume was the response to a request from Johannes Petreius, a printer in Nuremberg, who in 1542 was busy setting type for Nicolaus Copernicus’s milestone book, De revolutionibus (1543), when he invited Cardano to send him a manuscript for Petreius to print. Cardano was happy to do so, as Petreius was one of the respected scientific printers in southern Europe, and Cardano just happened to have been compiling horoscopes for years. The Libelli duo is a beautiful publication, as are most Petreius books. It has 67 genitures of emperors, popes, religious figures like Martin Luther, and a few scientists and artists. In his analyses, Cardano used the positions and alignment of zodiacal constellations and planets at birth to try to predict the major events of the individual's life. In the case of subjects long dead, this was not so hard; for living subjects it was not only more difficult, but riskier.

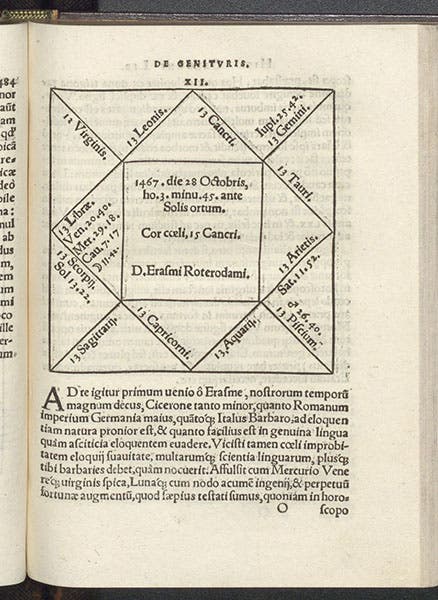

Some of the people chosen for horoscopes might seen odd for an Italian Catholic astrologer. Martin Luther, for example, would not seem appropriate for a Catholic, unless one is going to predict bad things, which Cardano did, even changing the year of Luther’s birth (which even Luther was not sure about). Desiderius Erasmus was a liberal reform-minded Catholic, but so was Cardano, which got him in hot water with the Inquisition late in life. And Giovanni Pico della Mirandola wrote a fierce denunciation of judicial astrology that was published after his early death and widely read. But perhaps Cardano himself had some doubts about his profession of the moment.

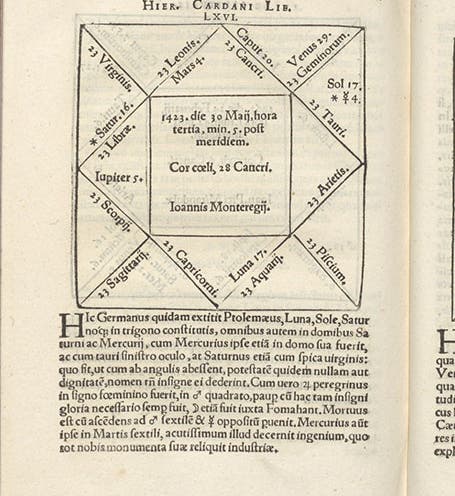

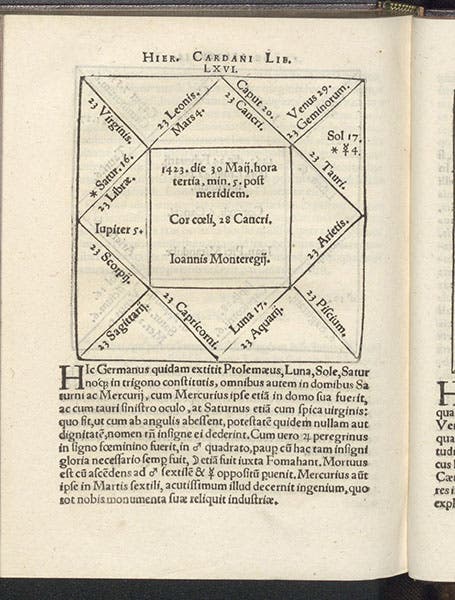

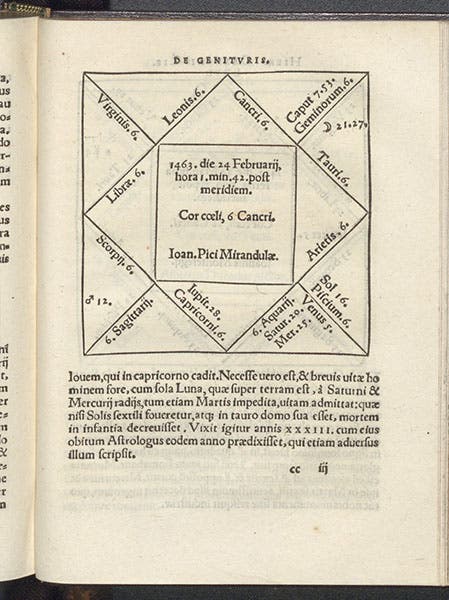

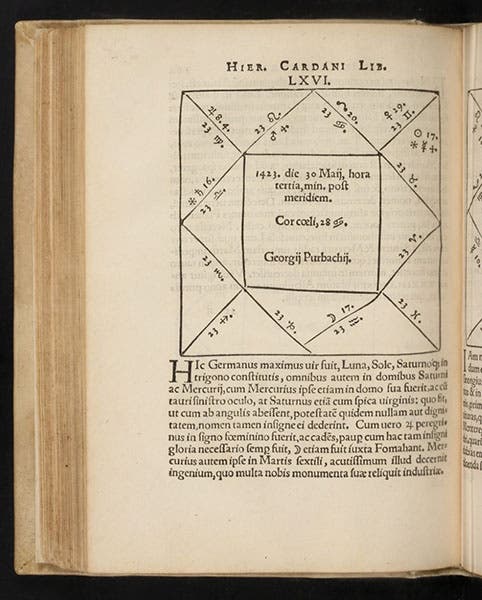

Interestingly, one of the horoscopes in the Libelli duo, that of Johannes Regiomontanus (first image), was sent to Cardano by Georg Joachim Rheticus, a friend of Petreius, and like Petreius, a Protestant, and an ardent Copernican. Actually, Rheticus sent four horoscopes to Cardano; in addition to the one for Regiomontanus, there was another for an older colleague of Regiomontanus, Georg Peurbach. We have written posts on both men, as they were the two most prominent Renaissance astronomers before Copernicus.

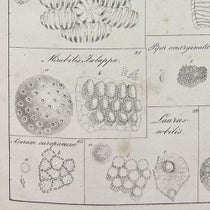

Cardano included the geniture for Regiomontanus in Libelli duo, but he got the horoscopes for Regiomontanus and Peurbach mixed up, so the printed horoscope is actually that of Peurbach, under the name of Regiomontanus. In 1545, Rheticus showed up on Cardano's doorstep in Milan, with a handful of additional horoscopes, including that of Andreas Vesalius, the Paduan physician whose 1543 book on anatomy was now quite the sensation, and Rheticus must have straightened Cardano out on Regiomontanus, because when Cardano and Petreius published the expanded Libelli quinque in 1547, the Peurbach horoscope was properly identified and included, and the real horoscope of Regiomontanus was added (shown in our first post on Cardano). If you compare the 1543 geniture for Regiomontanus (first image here) with the 1547 one for Peurbach (fifth image here), you will see that they are exactly the same, except for the names.

Unfortunately, in his analysis of the geniture of Regiomontanus, the Italian Cardano accused the German Regiomontanus of stealing much of his work from the Italian astronomer Giovanni Bianchini. The German Rheticus was none too pleased with this treatment of one of his heroes, and the two went from being friends to enemies, just like that.

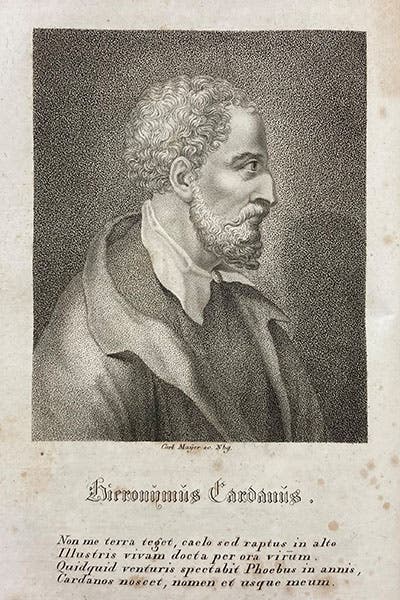

The portrait of Cardano that appeared in the Libelli quinque, which we included in our first post on Cardano, also appeared In the Libelli duo, right on the titlepage, as you can see in our second image. But we thought we would add an aquatint portrait that was printed in a little known multi-volume work on 7 late-Renaissance natural philosophers, called Lives and Teachings of Famous Physicists [Natural Philosophers} at the End of the XVI Century and at the Beginning of the XVIIth (1819-29), by Thaddä Rixner and Thaddä Siber, a German work that we have in our collections. If you are looking for unusual portraits or aquatints of Bernardino Telesio, Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella, and the like, you might check out this work.

Nearly everything that I know about Cardano’s astrology comes from a book by Anthony Grafton, Cardano’s Cosmos: The Worlds and Works of a Renaissance Astrologer (1999), which I highly recommend.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.