Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Domenico Cassini

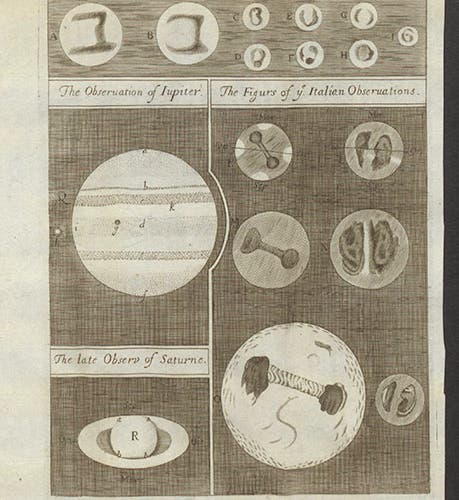

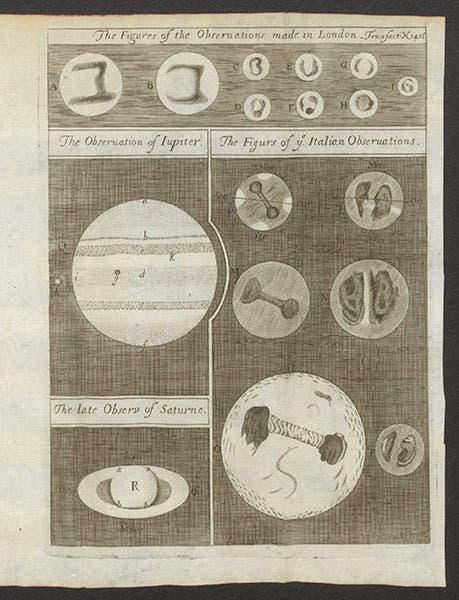

Markings on the surface of Mars, observed by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1665, on the right of this engraving (“ye Italian”), which also shows observations of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, by Robert Hooke, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 1, no. 14, 1666 (Linda Hall Library)

Giovanni Domenico Cassini, an Italian/French astronomer, was born June 8, 1625. Back in the days when Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) was all the rage, with its discussion of paradigm shifts, and its distinction between revolutionary science, science in crisis, and normal science, Cassini's work was the perfect example of normal science. He added to the fund of astronomical knowledge, discovered new entities and measured them carefully, helped develop better instruments, all within the existing paradigms, and without proposing anything revolutionary. This is, after all, what most scientists do, and Cassini did normal science more productively than just about anyone in the 17th century. In an earlier post, we talked about the meridian that Cassini erected in the church of San Petrono in Bologna in 1655, bringing the Sun into the Church, as John Heilbron once put it. Today we are going to discuss his observations of the planets, with a state-of-the-art telescope, and what he discovered. In future posts, we will look at Cassini’s attempt to measure the parallax of Mars in 1672, and so determine the size of the solar system; and at his monumental map of the Moon, completed in 1679.

In 1664, when Cassini entered into observational astronomy in earnest, the solar system consisted of Sun, Moon, and six planets (the Earth was now a planet), plus four moons around Jupiter (discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610) and one moon around Saturn (Christiaan Huygens, 1655). Huygens also discovered that Saturn has a ring. Cassini was at the University of Bologna, and around 1664 he obtained a refracting telescope made by Giuseppe Campani, one of the two most innovative telescope makers in Italy (the other being Eustachio Divini). One of the few surviving Campani telescopes is displayed in the Museo Galileo in Florence (third image).

With this telescope, Cassini observed the moons of Jupiter, and he was the first to see the shadows of the moons on the surface of the planet. He turned his attention to Mars, and found markings on its surface. His drawings of Mars were published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (identified as "ye Italian"), along with observations of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn by the Society's own Robert Hooke (first image). Although Cassini's drawings do not resemble modern maps of Mars, he was evidently seeing real features, for he used them to measure the rotation of Mars at 24 hours 40 minutes, a very accurate determination.

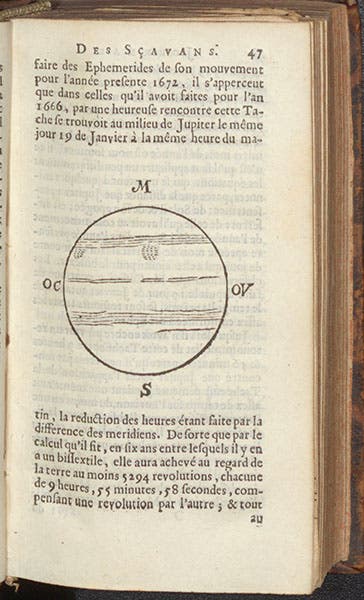

In the latter months of 1665, Cassini first observed a large spot near one of the southern belts of Jupiter. It persisted into 1666, and he used the spot as a marker to determine Jupiter's rotation period at 9 hours and 56 minutes. Cassini does not seem to have made a drawing at this time, and the spot subsequently disappeared. Then, in 1672, the spot reappeared, and this time Cassini coupled his announcement with a drawing (fourth image). Many astronomers feel that the formation Cassini observed was either the Great Red Spot itself, or its precursor. If so, this is one of its earliest depictions, preceded perhaps only by the Paris edition of the Journal des Scavans (the image here is from the edition published in Amsterdam).

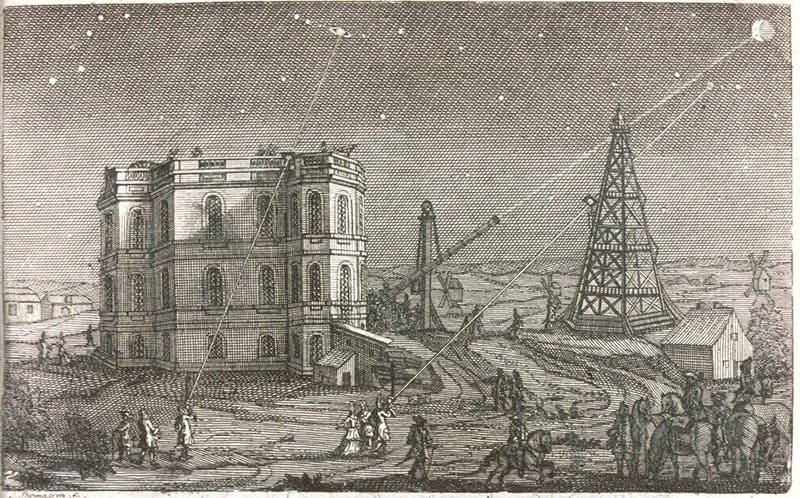

Cassini was invited by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Minister of Finance for King Louis XIV, to come to Paris to join the new Royal Academy of Sciences, and to direct the new Paris Observatory, then under construction. He arrived in 1669. He convinced Colbert to authorize the purchase of a 34-foot Campani refractor for the observatory; you can see it attached to a mast in a later engraving (fifth image), but intending to show the Observatory as it appeared shortly after it opened (the other telescopes depicted are aerial – tubeless – telescopes, first used successfully by Christian Huygens, who was also in Paris).

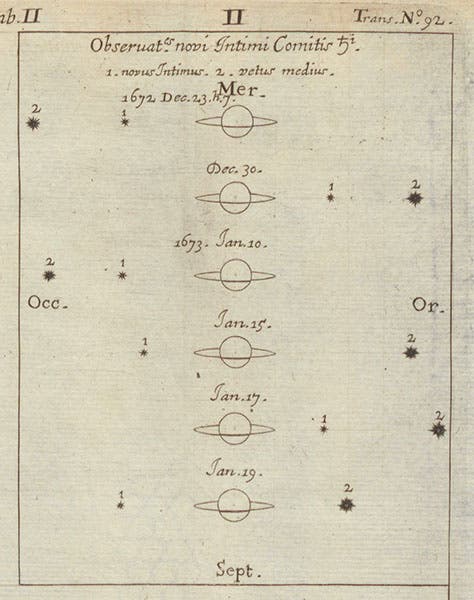

Cassini began observing Saturn with his new Campani instrument, and in 1671, he discovered a new moon orbiting Saturn, further out than the large moon Huygens had discovered (and which we now call Titan), and much smaller. A year later, he found a third moon, this one close to the planet, so he called it "Intimus"; we now know it as Rhea. We show part of an engraving accompanying the announcement of the discovery of Rhea, as it appeared in the Philosophical Transactions in 1672 (sixth image, above). The larger moon is Titan; the inner one is Rhea. Cassini would later find two more moons, announced in 1684, meaning that Saturn now had 5 moons, four of them discovered by Cassini.

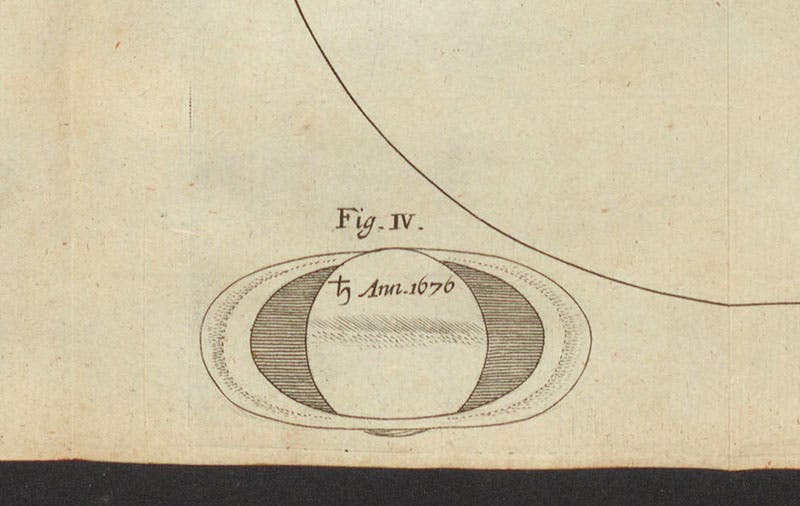

Perhaps Cassini's most famous astronomical discovery came in 1675, when he was observing the ring of Saturn. He noticed that the ring did not appear solid, as Huygens had seen it, but rather seemed to be in two parts, an inner and outer ring, divided by a darker region. This was a real feature, and it is now known as Cassini's division. It was first pictured in the corner of an engraving of sunspots that appeared in the Philosophical Transactions in 1676. We show a detail of that corner (seventh image). When NASA in 1997 sent a spacecraft to Saturn, they called it Cassini, in honor of his pioneering observations of the planet, and they named the Titan lander Huygens, both very appropriate names for Saturn vehicles.

Cassini had a long and fruitful career in Paris, observing until his death in 1712, and the Cassini legacy went on, as his son, grandson, and great-grandson were all distinguished astronomers, and are sometimes referred to as Cassini I, II, III, and IV. Our engraving of the Observatory (fifth image) appeared as a headpiece for a book by son Jacques, who was then director of the Observatory.

There is an oil portrait somewhere of Cassini I, often reproduced, but no one documents the portrait, and the reproductions are not of very good quality. The portrait was later the basis for several engravings, which are of excellent quality, and we use one of those for our portrait here (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.