Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Battista Hodierna

Giovanni Battista Hodierna, an Italian priest, astronomer, and microscopist, was born Apr. 13, 1597, in Ragusa, on the southern shore of Sicily. Hodierna’s life and work illustrates the problem of trying to engage in scientific pursuits while living in total isolation from others engaged in the same pursuits. He spent the first half of his life in Ragusa and the last half (from 1636 on) in Palma, now Palma de Montechiaro, also on the southern shore of Sicily, but further northwest. In Palma, he secured the patronage of the reigning dukes and was able to pursue his scientific interests without having to otherwise provide his own livelihood.

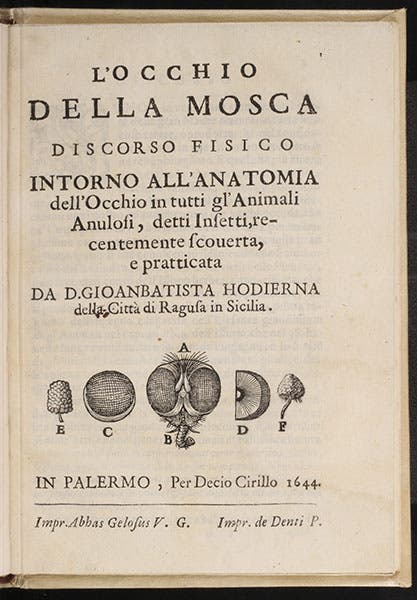

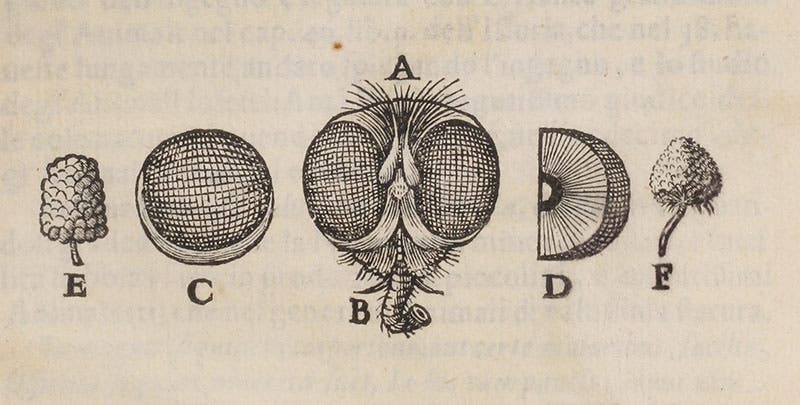

Hodierna was close to being a polymath, except that we usually require our polymaths, like Leibniz, to have some interest in philosophy and natural philosophy, which Hodierna apparently did not. One of his early interests was microscopy, which was unusual, to say the least, since the microscope was only about 20 years old when he made his own, and with one exception, no one had used a microscope to examine anything in nature. Hodierna chose to study the eye of a fly, which he dissected quite neatly. He compared its faceted structure, and its cross-section, to a mulberry and a strawberry. He published a short treatise, L’Occhio della mosca (The Eye of a Fly) in 1644, as part of a four-pamphlet Opusculi, printed in Palermo. We show the titlepage (second image, above), because it has a woodcut of his fly and its cross-section (and a mulberry and strawberry), and a detail of just the woodcut below.

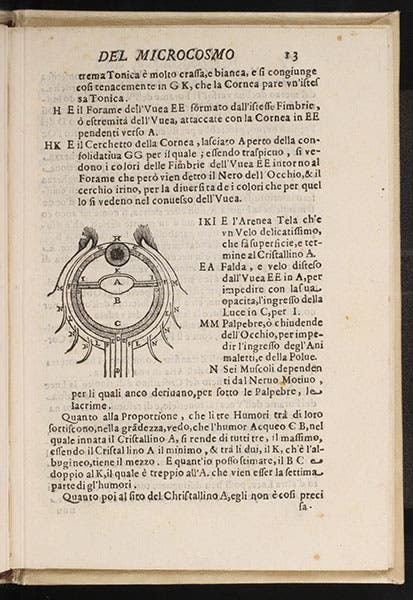

Another treatise in the Opusculi looks at the mechanism of vision and has a woodcut of a human eye in section (fourth image, just below). We have the Opusculi in our History of Science Collections, acquiring it in 2004 (it is available online), and we are fortunate to have even one of his treatises, for all of Hodierna’s works are quite scarce.

Although Hodierna’s Opusculi contained the first published microscopic dissection of anything, it had no influence, because apparently no one knew about it – certainly not Robert Hooke, who published his own engraving of a fly’s eye 21 years later. Hodierna tried valiantly to establish a correspondence network, with Jesuits such as Gaspar Schott (who had been in Sicily) and Giovanni Battista Riccioli, and even with Christiaan Huygens, and while no one really spurned him, the network never materialized. This is made evident from what is probably Hodierna’s most significant work, a two-part treatise that he published in 1654, called De systemate orbis cometici; deque admirandis coeli characteribus (On the System of Cometary Orbits, and on Wonderful Things in the Heavens). The latter treatise is a detailed examination of nebulae.

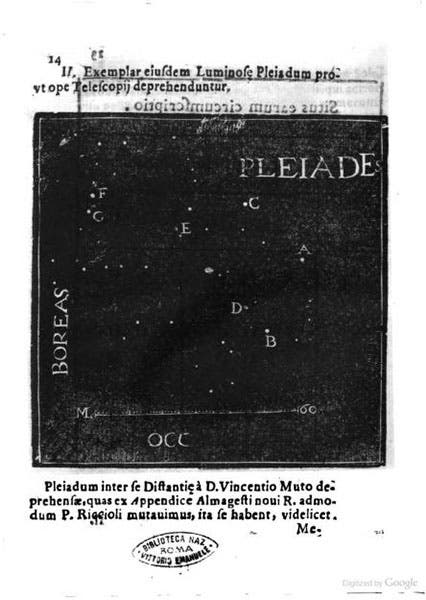

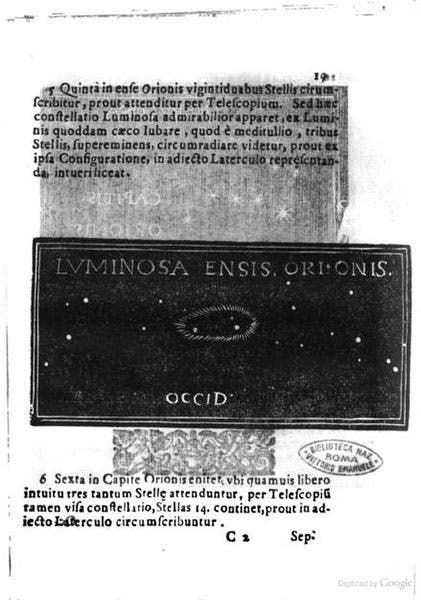

There were at the time only two new nebulae known, the Orion nebula and the Andromeda nebula, plus there were traditional asterisms such as the Pleiades and Praesepe (in Cancer) that had been known since antiquity, but no one had made a study of them, or looked for more. Hodierna did so, and discovered at least a dozen new nebulae, including M47 and M8, the Lagoon nebula. His basic premise was that all nebulae are collections of stars, although, with his less-than-excellent telescope, he could not find stars in every nebula (and we now know that the premise is incorrect – some nebulae are comprised only of gas and dust). The illustrations in his book are crude woodcuts; we include two of them, one showing that the Pleiades consist of many more than 6 stars (but Galileo had done this already; fifth image, just above), the other showing that the central bright spot of the Orion nebula (now called the trapezium) has stars in it – he found three (sixth image, just below).

This is observational astronomy of a high order, and the sad thing is, no one knew what he had done. All of his nebulae had to be discovered all over again in the 18th century, and when Charles Messier published his famous catalogue of nebulae in 1781, he knew nothing of Hodierna. It was not until 1985 – 1985! – that three Sicilian scholars discovered a copy of his book in Palermo and studied it carefully, realizing that Hodierna was really the father of nebula studies. They published their results in 1986, and since then, Hodierna has gained new respect in astronomical circles.

Hodierna died in 1660, still employed by the Dukes of Palma; I could not discover the location of his burial, although it was certainly in Palma de Montechiaro. Recently, as a result of his new-found fame as a pioneer of nebula studies, a stele and commemorative plaque were installed in his birth city of Ragusa. We show the plaque above. It is the only Hodierna memorial I know of, anywhere. I hope there will be more.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.