Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Battista Guglielmini

Linda Hall Lbrary

Linda Hall Lbrary

Linda Hall Lbrary

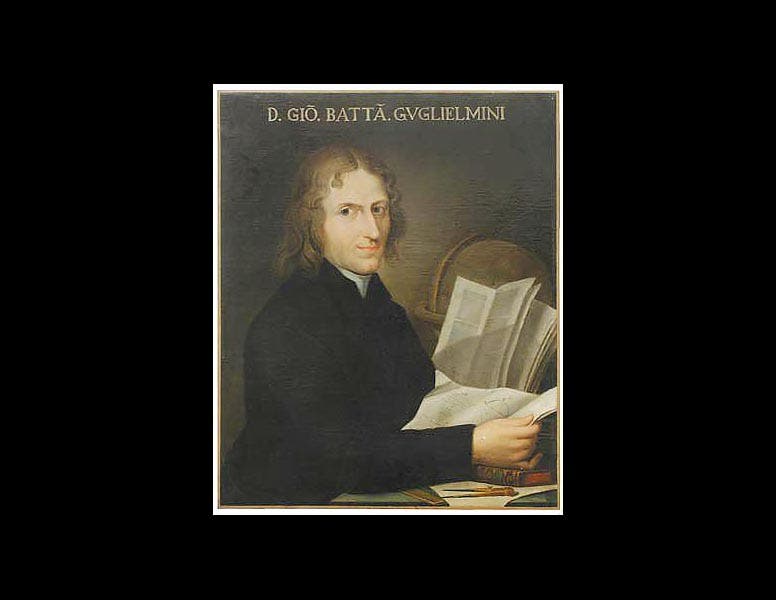

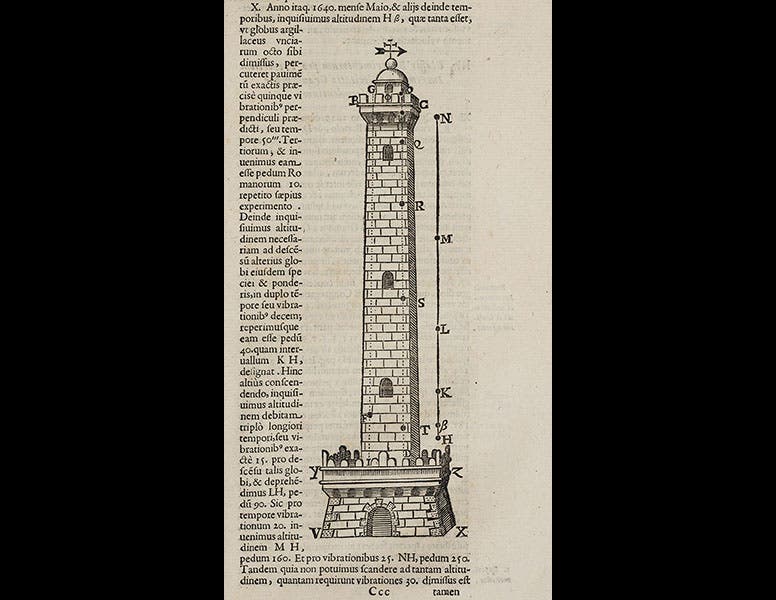

Giovanni Battista Guglielmini, an Italian abbé and physicist, was born Aug. 16, 1763. In the mid-17th century, about 100 years after Copernicus had proposed that the earth is a planet and rotates on its axis, there was a flurry of experimental activity trying to prove (or disprove) the rotation of the earth by dropping balls from high places. Since the top of a tower rotates faster than the bottom (if the earth rotates), it was thought that a ball dropped from a tower would not fall straight down to the bottom, but rather to the east. One of the most dedicated experimenters was Giovanni Battista Riccioli, who with his Jesuit brethren in Bologna, first calibrated pendulums to serve as timekeepers, and then dropped clay balls from the ramparts of the Asinelli tower in Bologna, which stands some 320 feet tall (first image). The results were inconclusive, which didn’t stop Riccioli from reporting on them at length in his Almagestum novum (1651) and including a woodcut of the tower (second image).

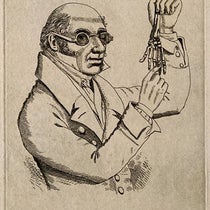

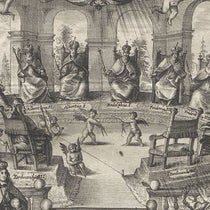

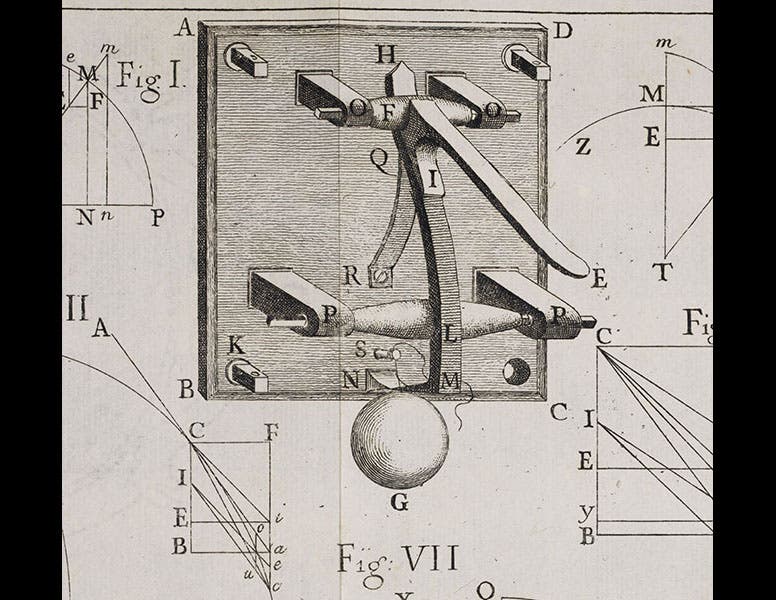

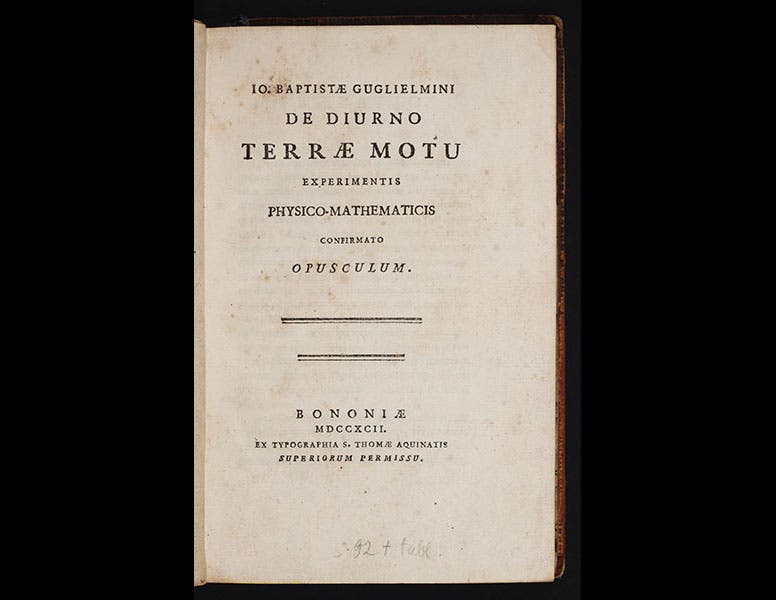

In 1790, Guglielmini reopened the matter. By then, physicists (like Guglielmini) could calculate rather exactly what the displacement should be, and Guglielmini wanted to show that experiment could validate prediction (and incidentally prove that the earth rotates). He initially wanted to drop balls from the cupola of St. Peters in Rome, thus allowing the Church to take the lead in recovering from the Galilean impasse, but ultimately he had to settle for the Asinelli tower. The practical difficulties were daunting. The predicted displacements, even in a tall tower like the Asinelli, were small - less that one inch. The Asinelli tower is over one degree out of vertical, so one would need a plumb bob almost 300 long to establish verticality. A ball dropped from a tower might be buffeted about by winds, and even the passage of carriages in the streets could vibrate the building and affect the results. To mitigate the wind, Guglielmini opted to drop his balls inside the tower, which meant he had to cut holes through several floors (third image). To lessen the passing-carriage effect, he worked in the middle of the night. He did experiments for over a year, but only a few of them were useful, because normally something was causing either the air or the tower or the plumb bob to be unstable. He also found out early on that even when conditions were good, the results varied dramatically, leading him to suspect that their method for dropping the balls was faulty. So he invented a device for just that purpose, which would drop a ball without imparting a sideways motion or spin (fourth image).

By 1792, Guglielmini finally had some good results, which showed a small displacement to the east and an even smaller displacement to the south. His results were published in De diurno terrae motu experimentis physico-mathematicis confirmato opusculum (Treatise confirming the motion of the earth by physico-mathematical experiments, 1792) (fifth image). His book spurred a number of investigations by Pierre Laplace and others that questioned some of Guglielmini's physical theory and disproved the deflection to the south. Nevertheless, the spirit of Guglielmini's attack on an immobile earth prevailed, and when in 1820, Giuseppe Settele petitioned the Roman curia for approval for a book advocating the motion of the Earth, he offered two pieces of evidence, and one of these was Guglielmini's book. The Church agreed (after a stormy debate), and in 1822, the ban on Copernicanism was officially lifted for all Catholics. The experiments of Guglielmini (sixth image) played a substantial role in this decision.

We acquired our copy of Guglielmini’s Opusculum from the London dealer Pickering & Chatto in 2005.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.