Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Battista Beccaria

Giovanni Battista Beccaria, an Italian physicist, was born Oct. 3, 1716. In 1748, Beccaria was appointed professor at the University of Turin, a post for which other factions were also lobbying, and Beccaria and his patron were subjected to a barrage of complaints that Beccaria lacked qualifications for the position. In 1751, Benjamin Franklin's work on electricity was introduced into Europe; in 1752, Beccaria’s patron heard about the "experiment at Marly," where a French experimenter had drawn electricity from the skies with a tall pointed rod, as Franklin had suggested one could, and Beccaria was immediately instructed to make this new field his own and silence the critics. This Beccaria did, in spades. In record time, he wrote and published a complete treatise on Franklin’s electrical theory, called Dell’ Elettricismo naturale ed artificiale (On Natural and Artificial Electricity, 1753, second image).

In the process, he went much further than Franklin in successfully explaining such things as the workings of the Leyden Jar (a bottle-shaped condenser) and the Franklin square (a flat condenser), why pointed objects could discharge electrified objects at a distance, and how lightning rods worked. He also discovered that the shape of discharges at points differed, depending on whether the point was positively or negatively charged, so one could now tell which direction the current was flowing.

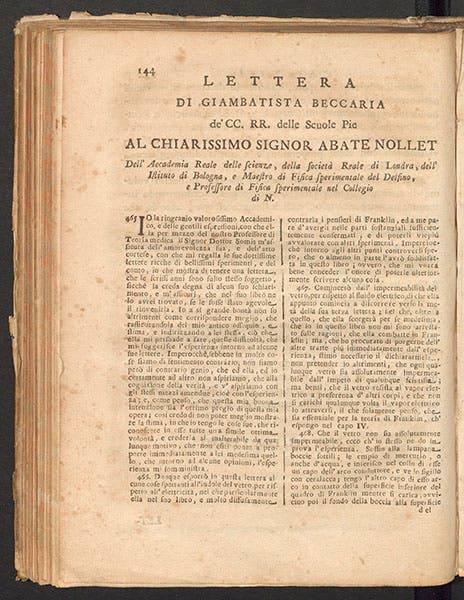

One of the interesting features of Beccaria's inaugural book is that it includes a letter to Abbé Nollet. Nollet was a prominent French electrician who rejected Franklin's one-fluid theory of electricity and preferred an effluvial theory, and he had many followers in Turin. They made life so difficult for Beccaria that he dashed off a fervid defense of "Philadelphian" electricity while his book was being printed, had the letter set in type, in a completely different font, and then inserted it right in the middle of his book (third image).

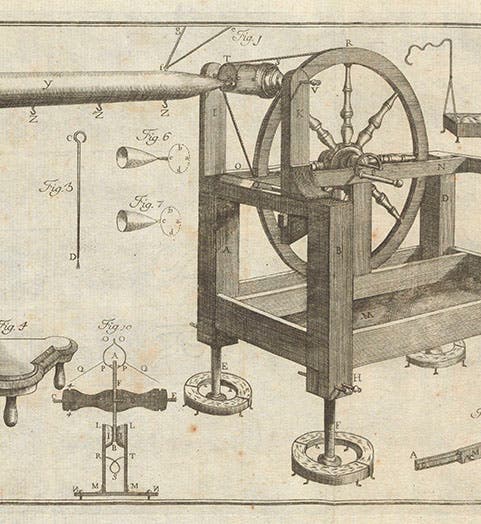

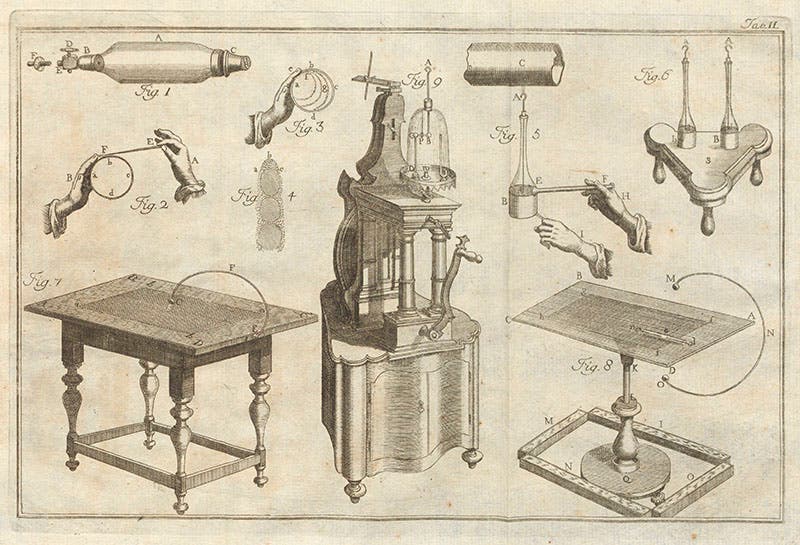

Beccaria expanded on his initial book in a barrage of subsequent publications. We have 15 titles by Beccaria in our collections, although several of them are duplicates. His Elettricismo artificiale (1772) examined in much greater detail electrical effects in the laboratory and, unlike his first book, was copiously illustrated with engravings of electrical apparatus. We display two of those illustrations here. The first shows one of Beccaria's static electricity generators (first image). Unlike Franklin, who used rubbed glass and resin rods almost exclusively, Beccaria preferred the more dynamic effects one can achieve with an electrical machine. Beccaria was also interested in studying electrical effects in a vacuum, as the other plate depicts (fourth image).

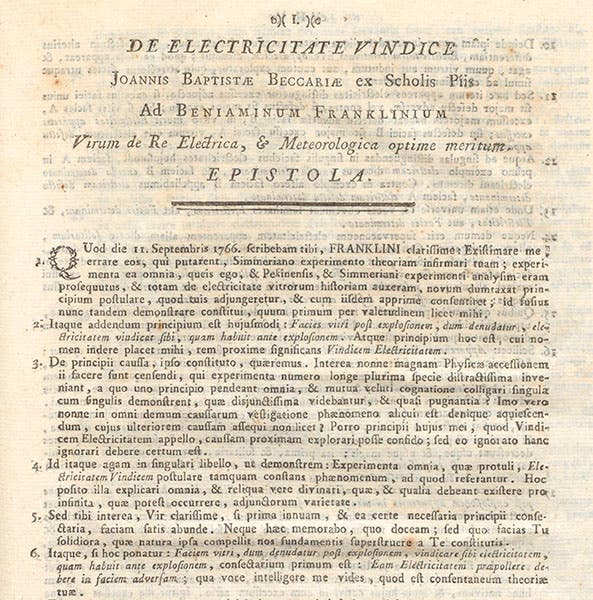

Franklin appreciated Beccaria’s aid in defending “Philadelphia electricity,” and the two corresponded. One of our Beccaria publications is a letter to Franklin published separately and dated Feb. 20, 1767 (fifth image). Indeed, it was in a letter to Beccaria (July 13, 1762) that Franklin described in great detail his newly invented “glass harmonica” that would soon take European musical salons by storm – in fact, it was the only time that Franklin described his invention at all. For that, Beccaria deserves at least some credit, for being such a trustworthy correspondent.

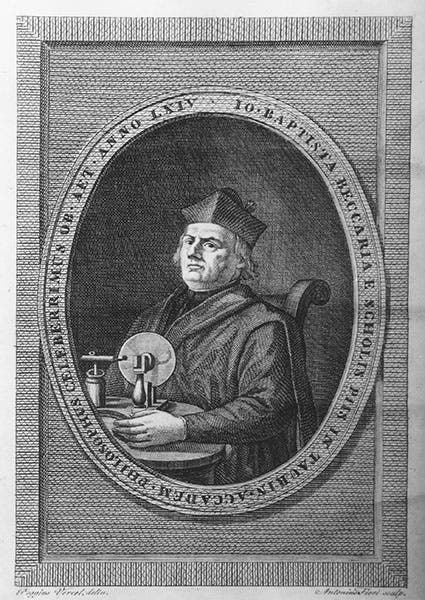

There is one Beccaria portrait in color that circulates on websites and is never sourced – it looks suspiciously 19th-century. So we show instead an engraving that is less attractive but has a greater chance of being authentic (sixth image). Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.