Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Aldini

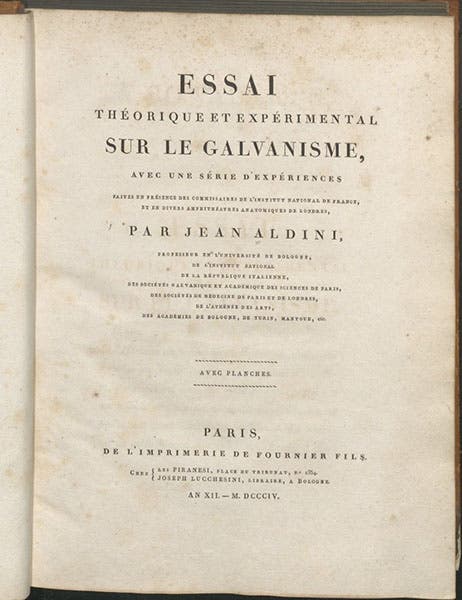

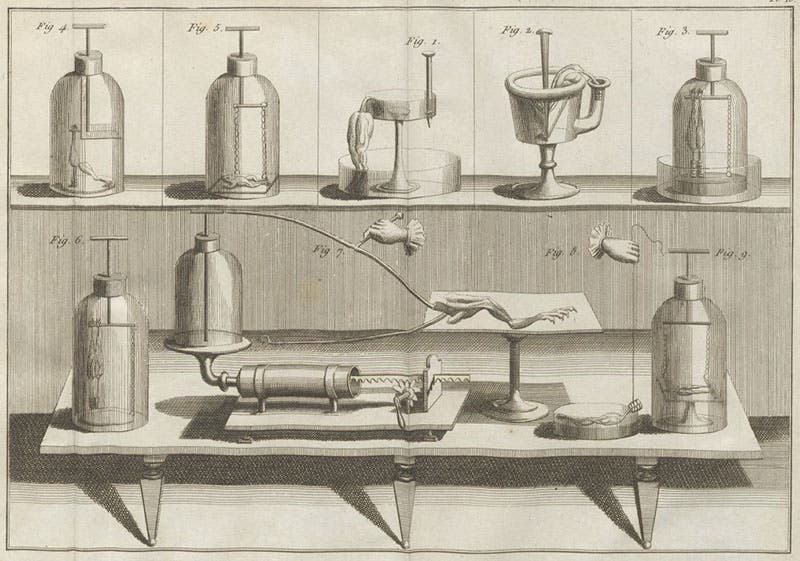

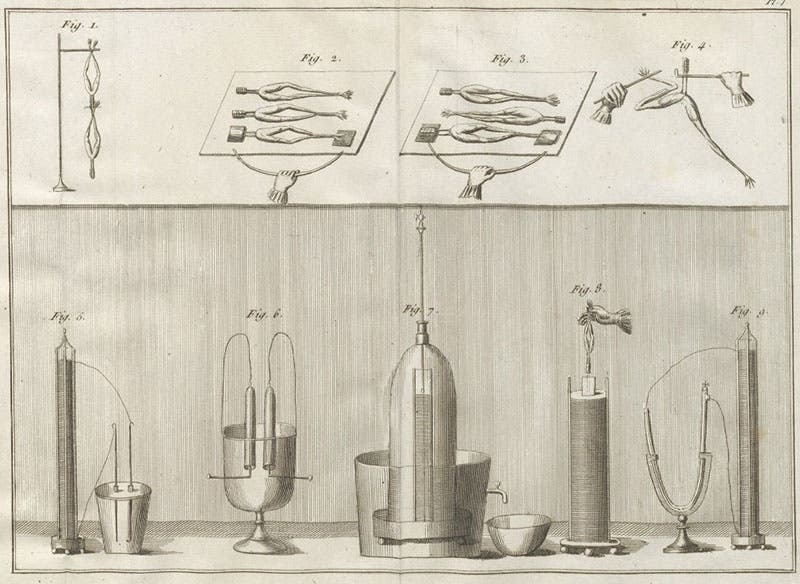

Giovanni Aldini, an Italian physicist, died Jan. 17, 1834, at the age of 71. Aldini was the nephew of Luigi Galvani, who in the 1780s performed experiments on dead frogs and discovered what he called "animal electricity." When a frog (or frog part) was touched with implements made of two different metals, the muscles would convulse, and Galvani thought that electricity was present in or being generated by the frog’s vital tissue (fourth image). Aldini helped his uncle publish his book in 1792 (see our post on Galvani), and when Galvani died in 1798, Aldini succeeded to the chair of physics at Bologna formerly held by his uncle.

Alessandro Volta, Galvani's rival and a professor at Pavia, had a different interpretation of Galvani’s frog experiments. Volta argued that the electricity was being generated by the two different metals, and the muscles were merely reacting to it – there was no such thing as "animal electricity." Volta would soon invent the battery (called then a Voltaic pile, invented in 1800), a sandwich of two different metals that generates “voltage,” to further argue his point. You can see the original design for a Voltaic pile at our post on Volta

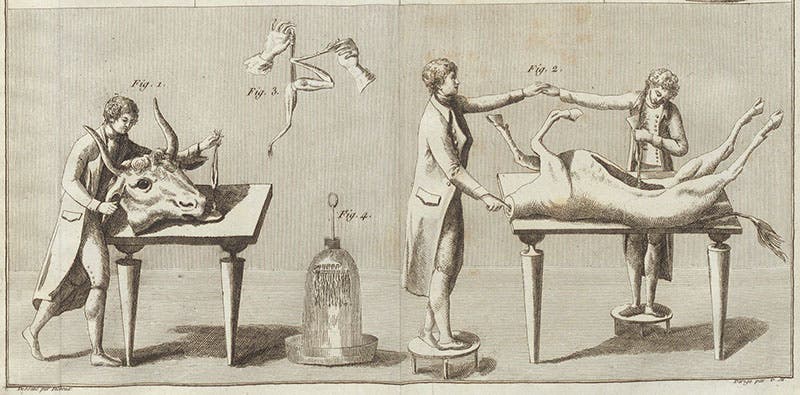

Aldini spent much of his career defending his uncle, with his most influential work being called, Essai théorique et expérimental sur le galvanisme: avec une série d'expériences faites en présence des Commissaires de l'Institut national de France, et en divers amphithéatres anatomiques de Londres (Theoretical and Experimental Essay on Galvanism: With a Series of Experiments Made in the Presence of the Commissioners of the National Institute of France, and in Various Anatomical Amphitheaters in London, 1804). We have this work in our collections, and as the subtitle tells us, the book is a record of demonstrations that Aldini gave to the National Institute in Paris (the revolutionary successor to the Royal Academy of Sciences), and at several anatomical venues in London. It is illustrated with 10 large engravings, which have provided all our images here except the portrait.

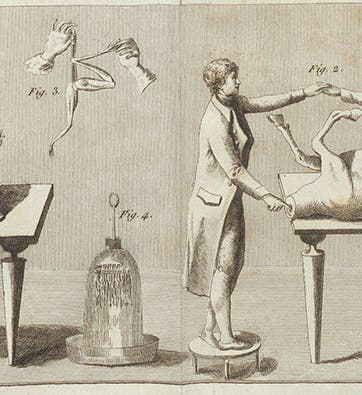

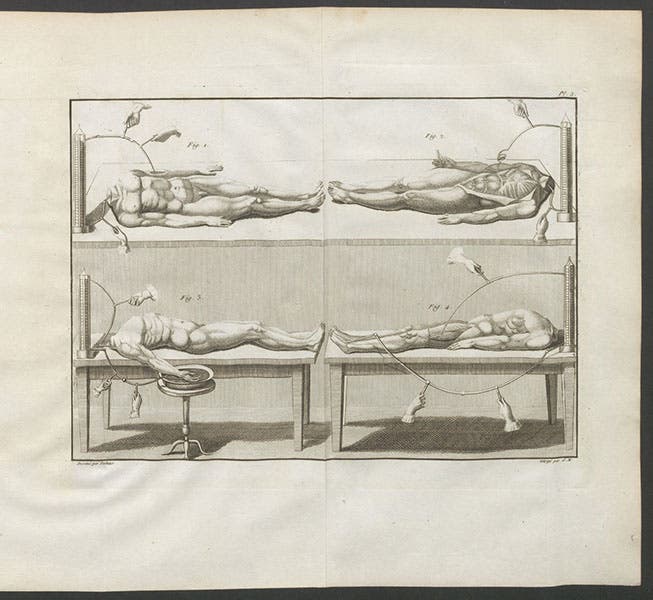

In his demonstrations, Aldini began with the carcasses of oxen and deer, attempting to show that animal electricity still resided in the dead flesh (first image). Interestingly, his instruments (the galvanometer lay far in the future) were frog-legs, which would kick in the presence of an electrical current (sixth image).

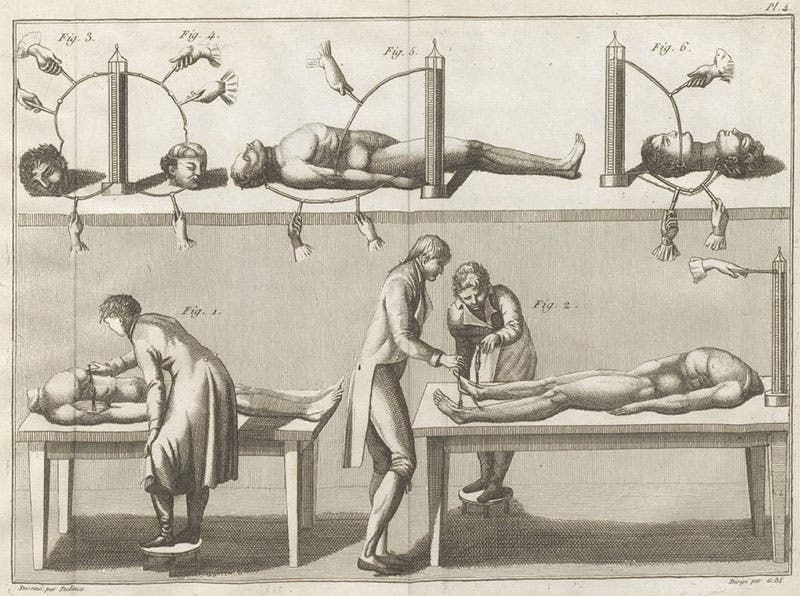

But by far his most dramatic experiments were on human cadavers. Here he brought the invention of his uncle’s rival, the Voltaic pile, into play, demonstrating that electric currents, applied to decapitated skulls, would cause faces to grimace and jaws to snap, and applied to the remaining cadaver, would result in all manner of muscular convulsions. You can see Voltaic piles in several of the engravings; they look like stacks of giant Oreo thins (fifth and seventh images).

While Aldini was demonstrating in London, on Jan. 18 of 1803, a notorious convicted murderer, George Forster, was executed at Newgate, and Aldini (along with several other individuals) was permitted to do public experiments on the recently deceased. Aldini's experiments were electrical; when he applied an electric shock to the victim’s face, the jaws contracted, muscles convulsed, and one eye popped open. Aldini was also able, using electrical stimulation, to make the cadaver raise its right hand and move its legs. The experiments seemed to indicate that electricity could revive, or at least stimulate, the dead.

It has often been suggested that Aldini’s electrical experimentation on the defunct George Forster might have been the inspiration for Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, The Modern Prometheus, which was published in 1818. There may be some connection, but it is well to remember that Mary Shelley was all of 5 years old when Aldini experimented on George Forster, and there was no description published in a readily accessible book that could have informed her of Aldini’s work, although there was a brief account added to the English translation of Aldini’s Essai sur le galvanisme, published in 1803, even before the French edition came out. We do not have the translation in our collections, but the “Appendix containing the author's experiments on the body of a malefactor executed at Newgate &c” was apparently unillustrated, or else we would surely see images of a convulsing George Forster in the secondary literature. Shelley did not mention Forster, or Aldini, in the introduction to her book. But she did say that she, Percy Shelley, and Lord Byron discussed “Galvanism” in the Villa Diodati in Switzerland on the evening before she got the idea for her book, so perhaps Aldini was influential in at least introducing that concept into English literary culture.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.