Scientist of the Day - Gino Watkins

Henry George "Gino" Watkins, a British arctic explorer, was born Jan. 20, 1907. After wallowing through school and showing little academic promise, Gino as a young man heard a talk by a man who had been with both Robert Scott and Ernest Shackleton in Antarctica, and he decided polar exploration would be just the thing for him. Not being able to find an expedition to join, he organized his own, and went in 1927 to Edgeøya, an island in the Svalbard archipelago. The next year, 1928, when he was just 21 years old, he organized an expedition to Labrador, mapping an unexplored area and learning to live in Arctic conditions.

Watkins had learned to fly while at Cambridge, and he knew that there was increasing interest in establishing a "Great Circle” route from Europe to North America. Such a route would fly directly over central Greenland, about which no one knew anything. The weather in particular was a complete unknown and would have to be studied and recorded. So Watkins, with the help of the Royal Geographical Society, organized a major expedition, the British Arctic Air Route Expedition (BAARE), that would explore eastern Greenland, and would set up a weather station on the top of the ice cap. This was a major expedition, involving 14 men, most of them young men like Watkins, and it is a testament to Watkins’s leadership skills that he was able to organize it and pull it off. On one thing everyone agreed: Watkins was a natural leader, and his men would follow him anywhere. The expedition even included two De Havilland Gipsy Moth airplanes, which were shipped to Greenland in crates and assembled there by the men. Clearly considerable mechanical dexterity lay latent among the crew as well.

The weather station was established on the top of the Greenland icecap, 112 miles from base camp on the eastern coast (and 8600 feet above sea level), and was manned by two-man teams in rotation for the first few months. Then, because of problems with food caches, which did not allow another two-man team to remain, young August Courtauld, whose father was footing much of the bill for the expedition, volunteered to winter over at the station alone, something that had never been done before, anywhere, under winter Arctic conditions. It was planned that he would be there in isolation from late December 1930 to the middle of March 1931, but three expeditions to retrieve him in March had to turn back, and it was not until May 5 that Courtauld, down to his last drop of paraffin, was found, his habitation and his instruments buried under the snow. This proved to be the most newsworthy event of the expedition, and since it was Watkins himself who broke through the tent ceiling and pulled Courtauld to safety, Watkins became even more famous back home. Before returning to England, Watkins decided (unwisely, everyone agrees) to make a 600-mile open-boat journey (with Courtauld and one other), down the eastern coast of Greenland and around the southern tip to the more settled western coast. This was a crazy venture, and they almost perished several times, but they survived, made it to civilization, and boarded a Danish steamer home in triumph. Watkins gave a talk to the Royal Geographical Society in the fall, they gave him the Founder’s Medal, and he was essentially offered the store – whatever he wanted to do next, they would back him.

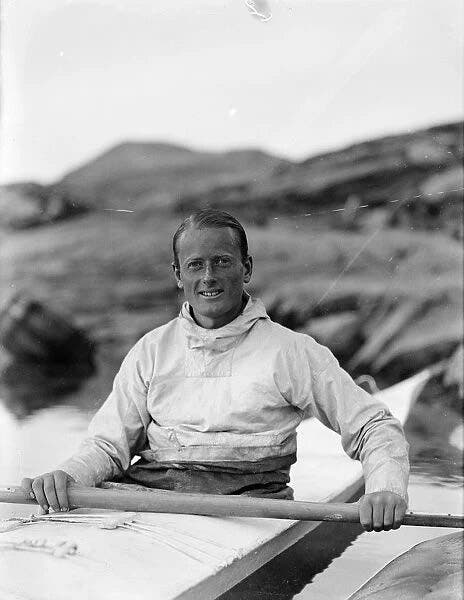

Initially, the next Watkins expedition was to be a trans-Antarctic crossing – what Shackleton had tried and failed to accomplish – but the Depression had settled into England and there were no funds available for such a venture, which would be expensive. So Watkins bided his time by heading back to eastern Greenland. At the end of BAARE, he had learned the art of Inuit kayaking and had a kayak custom-built for himself. He was the only member of the crew who mastered the “Inuit roll,” whereby he could return a kayak to its upright position without aid when it had rolled over. So on this day, Aug. 20, 1932, Watkins set off by himself on a seal hunt (hunting alone was a no-no for the Inuit) and never returned. His kayak was found later in the day, floating upside down. No trace of Watkins was ever found. He was 25 years old.

Quite a few books and book chapters appeared in the 1930s on Watkins and the BAARE, and on Courtauld’s exploit through the winter of 1930-31. There was even a biography of Watkins published in 1933 by one of the members of his crew. But Watkins slowly disappeared from historic view, and fifty years later, he was a little-known figure (except among polar explorers, who have always respected his skill and achievements). Fortunately for the rest of us, the masterful chronicler of alpine climbing and adventure, David Roberts, recently published a book on Watkins, Into the Great Emptiness: Peril and Survival on the Greenland Ice Cap (Norton, 2022). All I know about Watkins came from this book. I recommend it highly.

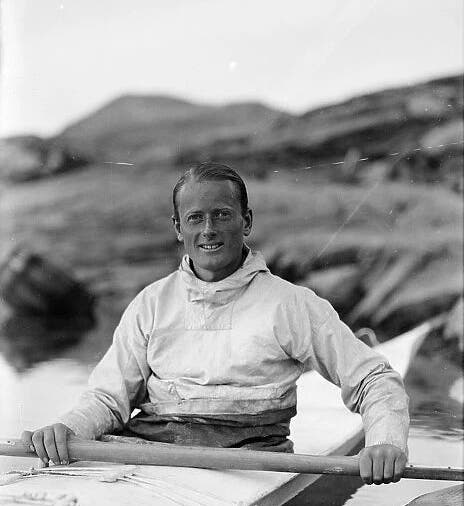

The Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) has some 1300 photographs in their archives relating to the BAARE, and some 39 photographs involving Watkins on their website that they offer for sale as reproductions. I hope they don’t mind if I show some of those here, since otherwise, photos of Watkins are hard to find.

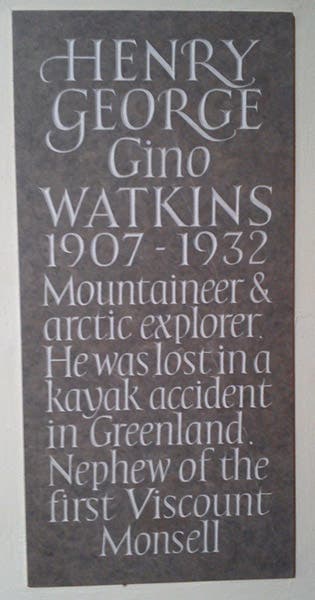

There is a memorial to Gino Watkins at St. Peter's Church, Dumbleton, Gloucestershire.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.