Scientist of the Day - Gilles Personne de Roberval

Gilles Personne de Roberval, a French mathematician, was born Aug. 10, 1602. Roberval is best known for his work in laying the foundation for calculus, with his “theory of indivisibles” (calculus itself would be discovered in the next generation, by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz). Roberval was also one of the original 7 members of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris, which was founded in 1666. And he played an important role in befriending and mentoring the young Blaise Pascal, when Pascal was introduced to the philosophic circle that met once a week in the convent of Marin Mersenne in Paris (others in the circle included René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi, and Pierre de Fermat). When Pascal and Roberval in 1646 heard about the new Italian barometric experiments of Evangelista Torricelli, Pascal repeated the experiments by filling a glass tube with mercury and inverting it in a bowl of mercury, at which point the mercury fell in the tube to a level of 30 inches, leaving an empty space at the top. Pascal claimed this space was truly empty, a vacuum. Roberval responded with an ingenious experiment in which he placed a deflated fish bladder in the tube before adding the mercury. When the tube was inverted, the fish bladder swelled up like a balloon, suggesting there might be some kind of rarified air at the top of the tube. But Roberval did not object too much to Pascal’s proposed vacuum, because Descartes was adamant that there could be no void space in nature, and Roberval and Descartes did not get along at all.

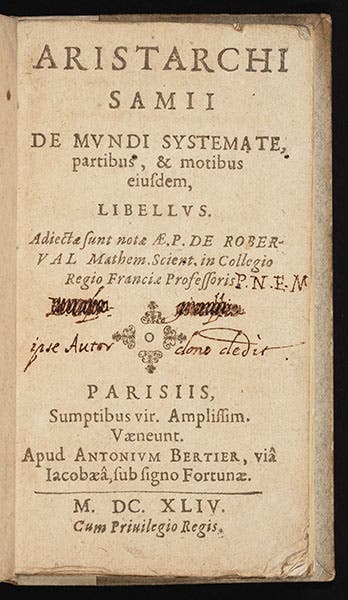

We have two works by Roberval in our Library. The first is Aristarchi Samii De mundi systemate (Aristarchus of Samos on the System of the World, 1644), in which Roberval pretends to have found a lost work by Aristarchus, supporting the idea of a sun-centered solar system (third image). In truth, Roberval wrote the work himself, and, with the connivance of Mersenne, passed it off as an ancient treatise. No one was fooled, except perhaps the theological censors at the Sorbonne, where Copernicanism was still under the ban of the Catholic Church.

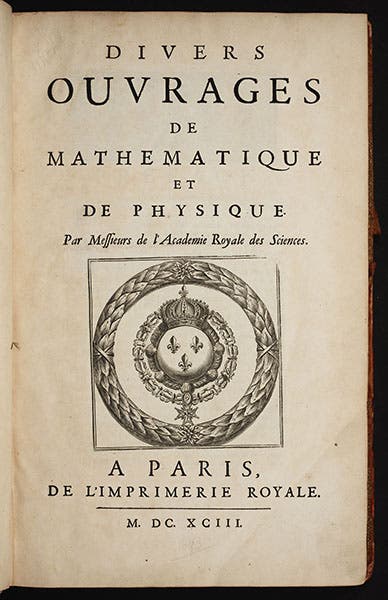

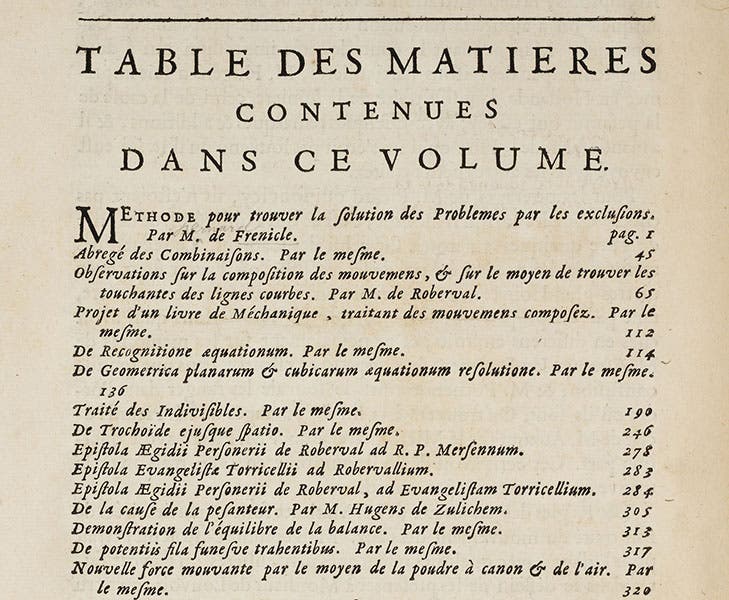

After the death of Roberval and various other Academicians, the Paris Academy published many of their manuscripts in a folio volume with the title Divers ouvrages de mathematique de de physique (1693; fourth image). The table of contents shows the 6 short treatises and 3 letters by Roberval that were included (fifth image).

In 1675, an artist, Henri Testelin, recreated with his brush the moment when King Louis XIV was introduced to his Academy in 1667 by his minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert (second image). It is said that the figure at left, behind the globe, is Roberval (detail, first image). We have never seen documentary evidence of this identification, but as a portrait of Roberval, it will have to do, since we have no other. The painting hangs in the palace at Versailles.

Finally, I thought I would mention an instrument supposedly invented by Roberval, called Roberval’s balance. This is an ingenious set of scales that uses a tetrahedral set of linkages so that the two pans always stay level no matter whether they are up or down, and with the interesting property that you can place weights anywhere on the pan, even at the edge, and it does not affect the weighing process. Numerous sources state that Roberval presented such a balance to the Paris Academy in 1669. Roberval balances are still being made and used, and “Roberval balance” even has its own Wikipedia article. If you go to the town of Roberval in northern France on the river Oise, there is a giant Roberval balance in the garden near the Roberval château (sixth image). For all this attention, no one mentions a source or contemporary description of the presentation or the balance. Roberval certainly could have invented such a device; he wrote a hefty treatise on mechanics, unpublished and now lost, that had an entire chapter on the balance. But it would be nice if someone could authenticate the story.

This is a revised version of an essay first posted on Oct. 15, 2017.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.