Scientist of the Day - Gideon Mantell

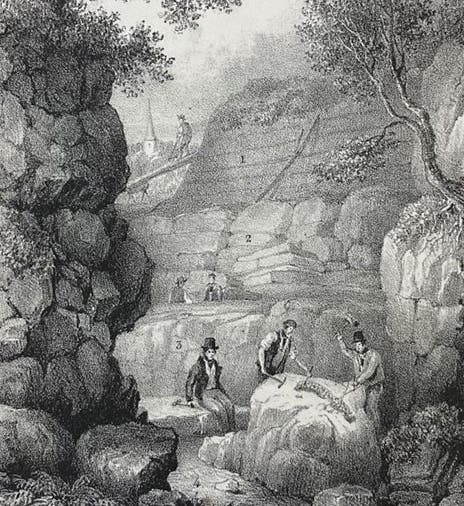

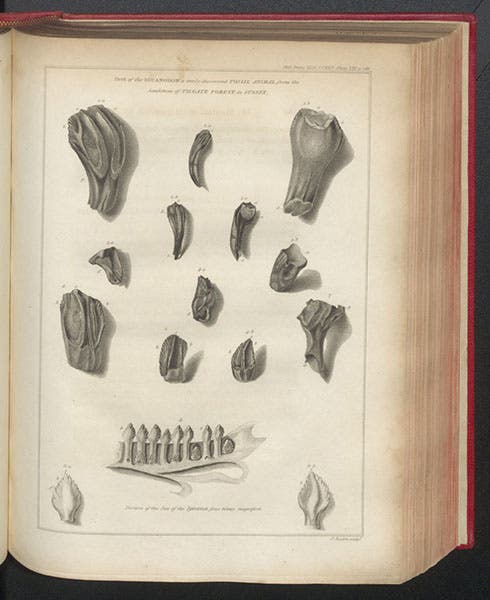

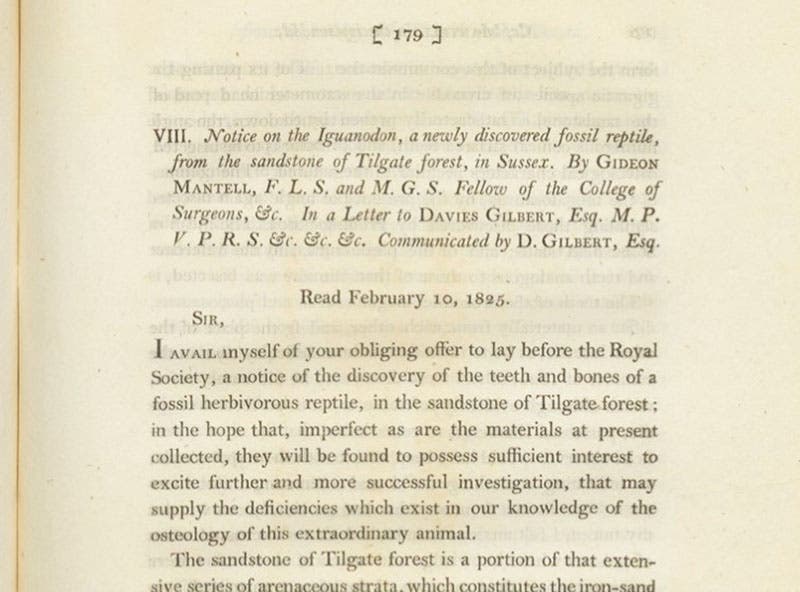

Gideon Mantell, an English surgeon, was born Feb. 3, 1790. Mantell grew up in Lewes, Sussex, in southeast England, and was apprenticed to a surgeon there. After failing to land an assistantship in London, he settled down to practice in his hometown. From an early age he had collected fossils, which are especially rich in that part of England, and it grew to be a passion. Sometime around 1820, he began to turn up unknown teeth, seemingly reptilian, in his favorite hunting spot, Tilgate Forest. Other large bones, possibly related, were found as well. He sent one tooth to the great Baron Cuvier in Paris in 1823, who pronounced it that of a hippopotamus, but Mantell disagreed, and persisted. Still, he could not figure out what kind of animal had such teeth. His conceptual breakthrough came in the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in London, where he saw the jaw of an iguana, and realized that his fossil teeth were quite similar, but 20 times larger. He envisaged an extinct giant iguana, perhaps 100 feet long, that roamed the Weald in what we would now call the Cretaceous era, and he settled on a name, Iguanodon. He published a paper in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1825, with an engraved plate showing some of the teeth, and an iguana jaw for comparison (here is a detail of one of the teeth, from our exhibition, Paper Dinosaurs, available online). A year earlier, William Buckland had described another Mesozoic reptile, this one carnivorous, which he called Megalosaurus. In 1842, they would both be designated as dinosaurs, the first two discovered and described.

While it is often claimed that the first Iguanodon tooth was found by Mantell’s wife Mary Ann while he was making a house call, there is no evidence supporting that legend. There is no doubt however that Mary Ellen was an able fossilist and artist, and that she found some of the teeth, and a few of the larger bones, and engraved some of the drawings for Mantell’s first book in 1822.

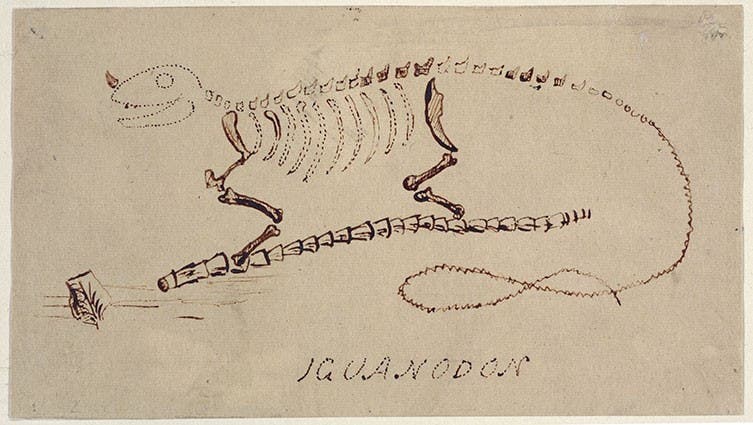

For some years thereafter, Mantell lacked sufficient Iguanodon bones to make an informed reconstruction. There survives one drawing made by Mantell himself that offers up a possible Iguanodon (fifth image, below), and another by the engraver and artist George Schaff, made under Mantell’s guidance, that portrays in color a Cretaceous swamp, with Iguanodon, looking very much like a giant iguana, on the left (sixth image, below). Both reconstructions featured a nasal horn; this is the result of a horn found by Mary Ann in 1824, that was originally assumed to be mammalian, and then proved otherwise. They placed it on the Iguanodon snout because that is where horns go. It was later determined that the horn was actually a thumbspike, but that would not be known until the 1880s. You can see a lithograph of the horn here.

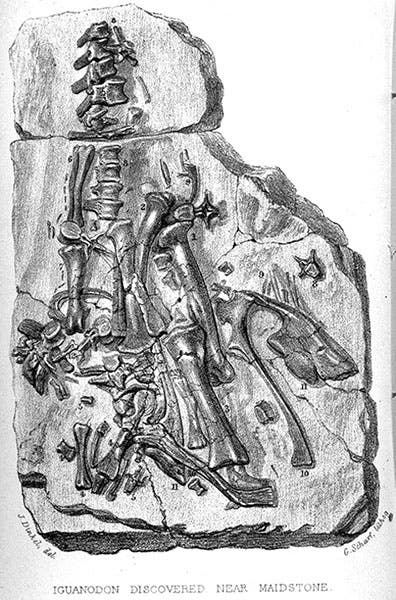

Finally, in 1834, a slab of fossilized bones was discovered in a quarry in Maidstone, Kent, which turned out to contain much of an iguanodon skeleton (seventh image, below). Mantlell could not afford to buy it, but his friends stepped in and acquired it for him. He chipped away at it for years, without being able to remove the bones from their matrix. It was called the “Mantell-stone” by others, and Mantell eventually sold it to the British Museum, where you may see it today.

When Mantell published his Wonders of Geology in 1838, he allowed the artist John Martin to attempt his own reconstruction for the book’s frontispiece; the battle-scene was captioned “Country of the Iguanodon.” You can see it here.

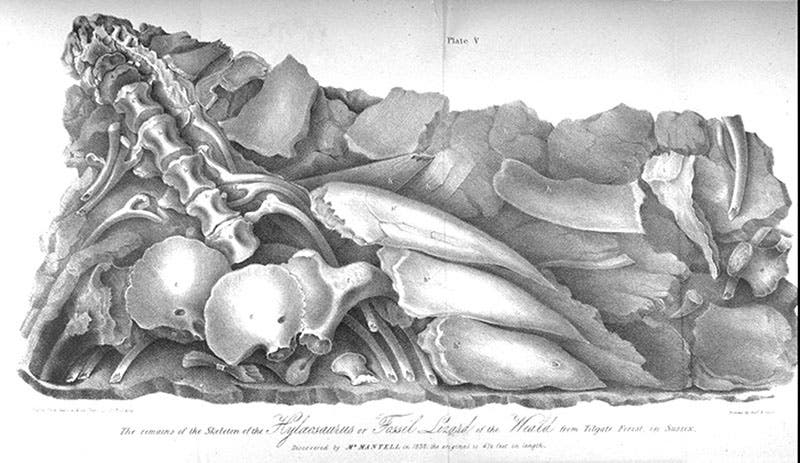

Two years before the Maidstone iguadodon was unearthed, Mantell had found a similar kind of slab himself, but the bones it contained were not iguandonian. It was instead a large unknown reptile with a set of spikes that seemed to have run down its spine. Mantell published the discovery in The Geology of the South-East of England (1833), calling it Hylaeosaurus, the lizard of the woods, and including a lithograph of the slab (eighth image, below). Mantell had found two of the first three dinosaurs known to the scientific world.

The rest of his life was not so happy. Mantell failed to find patients in his new home in Brighton, went broke trying to run a museum there, and had to sell his specimens to the British Museum. Then his wife left him in 1838, an 18-year-old daughter died the next year, and in 1841, he was in a bad carriage accident, which left him in extreme pain and with a damaged spine. He fought the pain with opium, and finally, in 1852, he stilled the pain for good with a massive overdose of opiate. For a man with such a troubled life, he left a large literary legacy. His Wonders of Geology, in particular, was very popular and went through numerous editions and translations in just a few years (we have three in our collections).

Mantell was also an excellent geologist, which was not typical of fossil collectors, and he was aware, before most, that different rock formations contain different kinds of fossils. He was one of the best friends and correspondents of Charles Lyell, 7 years younger, who would revolutionize geology in England after 1830. We will devote a future post to Gideon Mantell, geologist.

This is a revision of a post that originally appeared on Feb. 13, 2015. One image has been removed, one replaced, and four new images have been added. The text has been rewritten and expanded, and captions have been added for all images.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.