Scientist of the Day - George Washington Ferris

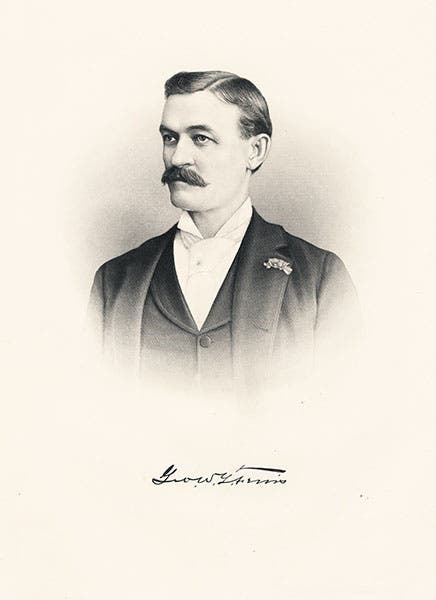

George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr., an American engineer, was born Feb. 14, 1859, in Illinois. After a childhood in Nevada, he attended school in California, and then studied engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) in New York, an institution that turned out many of American's top engineers at the time. Ferris was interested in the engineering potential of structural steel, and he established a company in Pittsburgh to test structural steel and to build bridges, starting with one over the Monongahela River at 6th St. in Pittsburgh (since demolished, like all of the Pittsburgh river bridges of the 1880s and 1890s). He was apparently very good at his job and a genius with steel.

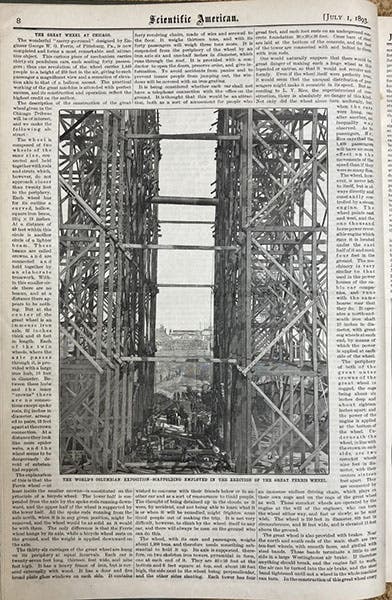

In 1891, the World’s Columbian Exposition was getting ready to open on the Midway in Chicago in the spring of 1893, and the Director felt that they lacked a “wow factor”, like the Eiffel tower that made its debut at the Paris Exposition in 1889. So he issued a challenge to the nation's engineers: what can we build at our Exposition to trump the French? There were not interested in a tower, even if taller. Ferris had apparently already had an idea for a vertical wheel to carry sightseers up into the air, but now he began to think more grandly, and he proposed a gigantic version of his wheel to the fair organizers. There were initial questions about safety, and whether it would work, but Ferris was persuasive, and apparently his idea was better that the proposals of anyone else, and his idea was finally approved. However, he would have to bear construction costs himself, and even worse, it was now mid-December 1892, and the exposition was set to open four months later.

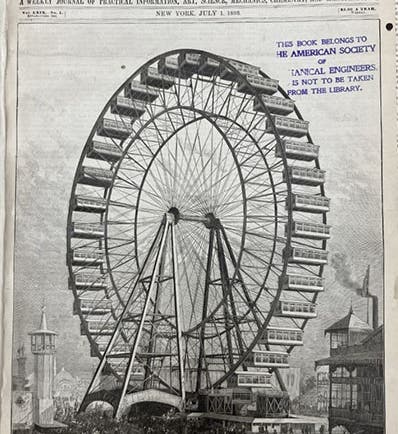

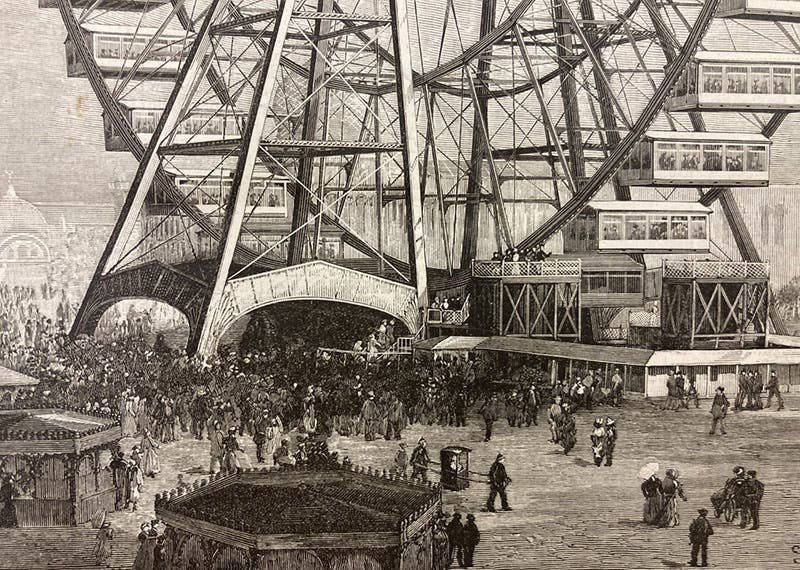

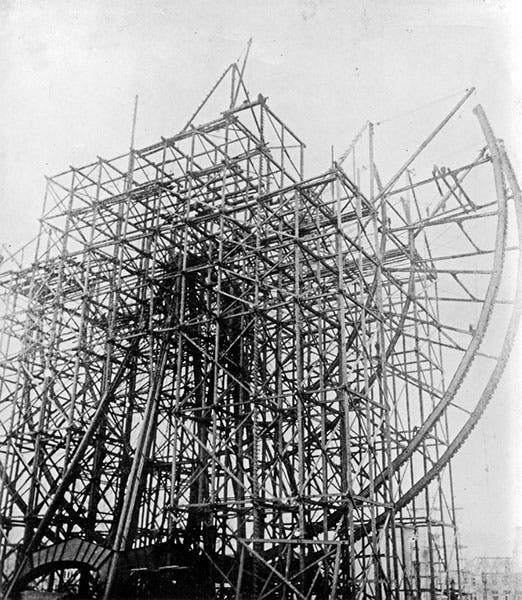

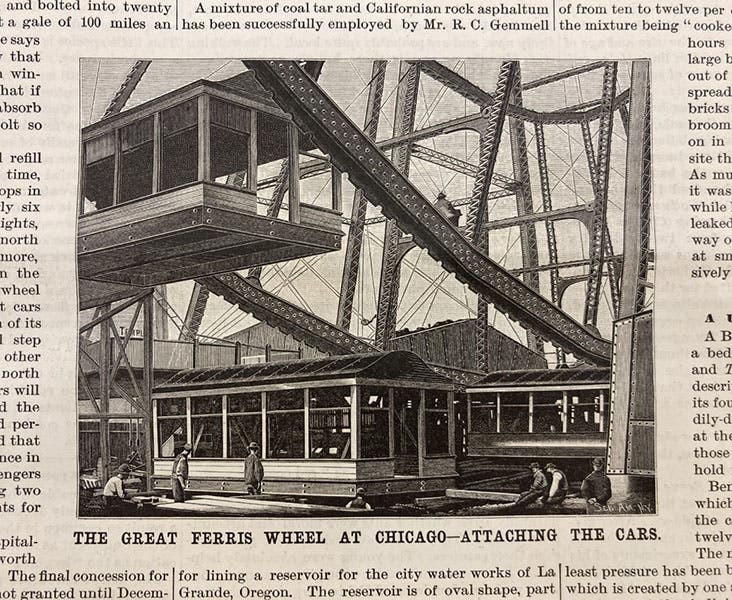

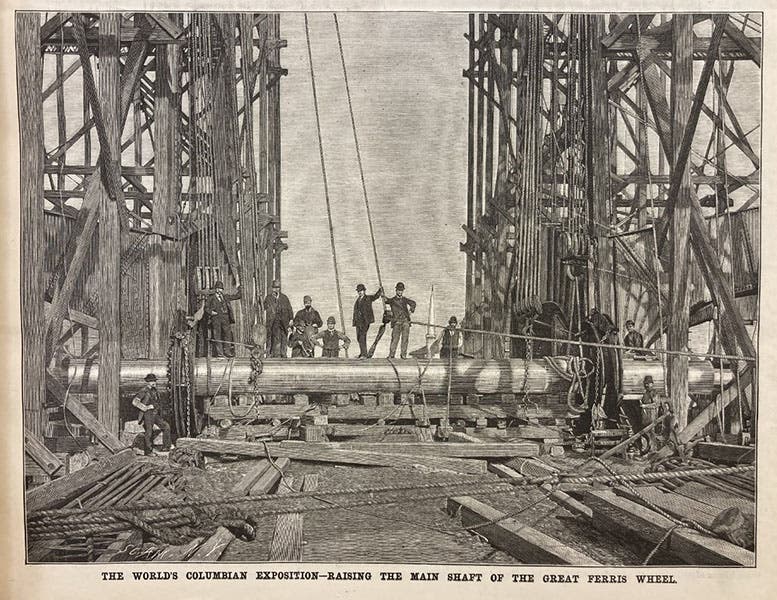

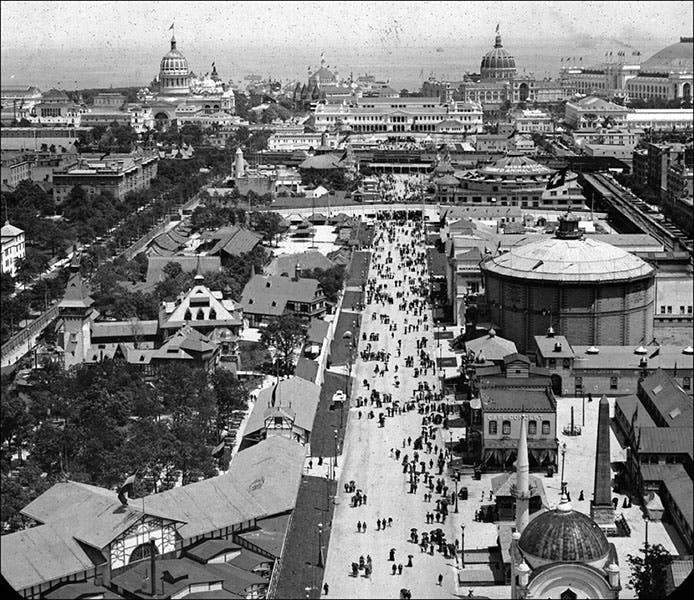

Incredibly, Ferris raised funds, ordered steel, built foundations, and had the wheel up and running by June 11, 1893, not quite in time for the opening, but still a remarkable feat. Equally amazing, since there was no precedent for such a gigantic wheel, it worked perfectly – there were no accidents of any kind. The wheel was what is called a tension wheel, which means it was held together by tension wires, just like a bicycle wheel. The largest tension wheel that had been built to that time was 30 feet across. Ferris’s wheel was 250 feet across, carried 36 gondolas, each of which had 40 seats but could carry 60 passengers, and the riders at the top were 264 feet off the ground and could see further than anyone in Chicgo had ever seen before. The main axle was 45 feet long and weighed 45 tons and was the largest piece of forged steel ever fabricated in this country.

The Ferris wheel drew immense crowds for the six months of the fair, carrying 1.5 million passengers and pulling in $750,000 at fifty cents a pop. Ferris became America’s most famous engineer almost overnight, and he was only 34 years old. But it was one of the few bright spots in the rest of his life. There was considerable contentiousness between the Exposition committee and Ferris's company as to how profits were to be distributed, once receipts paid off the cost of construction (which was about $364,000), and Ferris came out of the lawsuits much poorer than he expected. He was certainly not happy when Chicago dismantled the Wheel after the fair closed, although it was re-erected in Lincoln Park as a sight-seeing attraction. Apparently, Chicagoans had a more short-sighted view of their monuments than Parisians, who allowed the Eiffel Tower to stand right where it was built. Ferris’s health had suffered during the ordeal of construction and went further downhill during the subsequent litigation. Then his wife left him. And in 1896, he came down with typhoid fever; he was hospitalized, and breathed his last on Nov. 22, 1896. He was 37 years old.

Ferris’s wheel had a little more life in it. It wasn’t bringing in much revenue in its Lincoln Park location, since the park did not have a liquor license, so when some entrepreneurs wanted to buy it, take it down, and ship it to St. Louis, the city was happy to bid the wheel adieu. It was re-erected in St. Louis for the Pan-American Exposition of 1904. When that fair was over, the wheel was brought down with TNT, collapsing into a mass of scrambled steel and sold for scrap. It was an ignominious end to a marvel of civil engineering.

The original wheel may have perished, but as everyone knows, the idea of the Ferris Wheel caught on, and thousands were built, smaller and more portable, for county fairs across the country. And they have always been called "Ferris wheels”. Ferris has achieved some kind of immortality after all, although one must note that the two largest modern Ferris wheels, the only ones to exceed the scale of the 1893 wheel, have dropped the name Ferris, and are called "The Eye” (London), and “The Flyer” (Singapore).

Most of our images were drawn from a Scientific American article in their July 1, 1893 issue, just two weeks after the Ferris Wheel was inaugurated. The front cover (first image) showed the scene at the opening; we also show a detail of that cover, showing the crowds and the gondolas at the bottom of the wheel. Two of our images, a photo of construction in process (fifth image), and photo of the Midway from the top of the wheel (eighth and last image), came from a useful website called “Chicagology,” with many images of the 1893 wheel. There also survives a brief 50-second film of the wheel in motion, made in 1896 at the Lincoln Park location.

Recently, it was announced that the 45-ton main shaft has been located by a metal detectorist, in St. Louis, buried underground, not far from where the Ferris Wheel stood in 1904. Or at least he detected a 45-foot-long metal object buried there. As it lies under a road, it may not be excavated anytime soon. But if it hasn’t completely rusted away, it might be nice to dig it up someday and give George Ferris a physical monument that we can walk up to and touch.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.