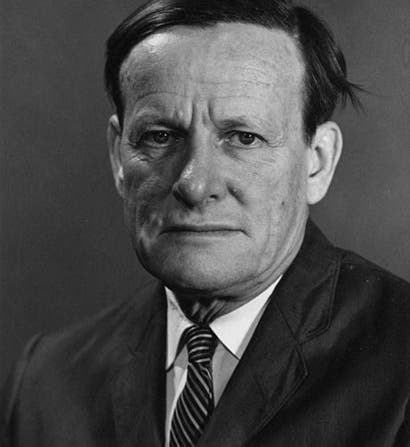

Scientist of the Day - George Ledyard Stebbins

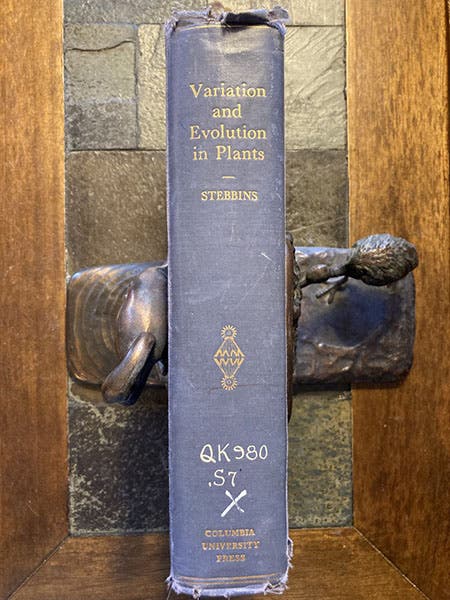

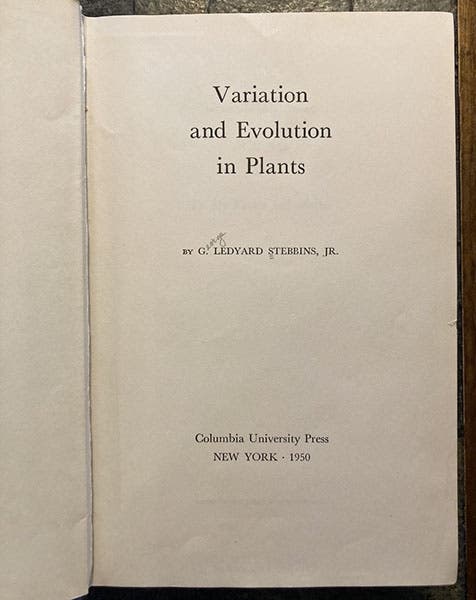

George Ledyard Stebbins, an American botanist, was born Jan. 6, 1906. Stebbins was one of the architects of modern evolutionary theory, often called the Modern Synthesis, a construct of the 1940s and 1950s, when evolutionary zoologists and botanists, population geneticists, and paleontologists forged from their respective disciplines a restructured evolutionary theory, showing how genetics makes sense of evolution, and evolution makes sense of fossils, with vice versas all round. Stebbins was the botanist in this group, which also included Theodosius Dobzhansky, Ernst Mayr, and George Gaylord Simpson. Stebbins’ principal contribution was a book, Variation and Evolution in Plants (1950), which showed how genetics and natural selection provide the keys to explaining plant speciation. I retrieved our copy from the closed stacks, its battered condition indicating that it had been well perused by many readers. We bought it on Aug. 15, 1950, for $8.00, it says in pencil on the dedication page, when our Library was only 4 years old (and when we still wrote call numbers in white ink right on the spine). We should probably transfer the book to the "Cage", our holding area for books that are now rare books but not yet rare enough to be moved into the vault.

Stebbins took his Harvard PhD in botany to the University of California at Berkeley, where he wrote his book. He then moved on to the University of California – Davis, where he established a Department of Genetics, teaching there until his retirement in 1973. One of my former colleagues, philosopher of science George Gale, remembers a seminar that he took at UC-Davis (once upon a time) in which Stebbins participated. Since the seminar was convened by a philosopher of biology, a breed who like to tell biologists (and botanists) how they ought to be doing their jobs, George recalls at least three occasions when Stebbins stomped from the room in disgust, only to return at the next meeting to go at it again with Marjorie Grene (the philosopher, and something of a legend in her own right). Ah, those were the days, when scholars would get so mad they could spit, all because they disagreed over the meaning of the word "adaptation."

Stebbins lived for 27 years after retirement, during which time he remained quite active. I remember using a textbook, Evolution, which he co-wrote with Dobzhansky and 2 others in 1977, and he published a book of evolutionary readings in 1982 – I still have both volumes. He lived for such a long time that, like Sewall Wright, he attracted a biographer while he was still alive. Vassiliki Betty Smocovitis, a historian of evolutionary biology at the University of Florida, wrote a delightful article (Journal of the History of Biology, 1999) in which she discussed the advantages of having your principal subject still available for interviews, and the downside, as not only did Stebbins want to have final say, but so did many of his family and acquaintances, which made life difficult. She remembered when, after sorting out all his papers, she got a call announcing that they had discovered several dozen more cartons of papers in the garage. And she noted how disconcerting it is when your hero (who was in his 90s at the time) bursts into tears because his infirm wife is not available to help him pack his suitcase for a meeting.

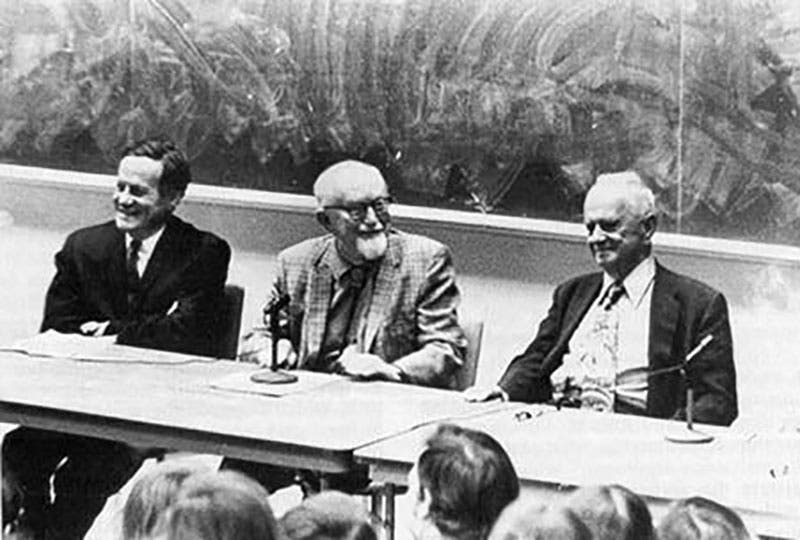

There are not many photographs of Stebbins to be found in the archives at Berkeley and Davis, and even fewer that show him interacting with colleagues, which is surprising. The best is one from the 1960s and shows him (at the left) in front of an audience with Simpson (center) and Dobzhansky (right) (fourth image).

Stebbins died on Jan 19, 2000, at the age of 94.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.