Scientist of the Day - George Gibbs and Benjamin Silliman

Early on the morning of Dec. 14, 1807, an enormous fireball passed over Vermont and Massachusetts and exploded over the small town of Weston, near Fairfield, Connecticut. Stones fell in a number of places in and around Weston. Benjamin Silliman, a professor of chemistry and geology at Yale, rushed over with a colleague to interview witnesses and collect whatever fragments he could find. We featured Silliman as a Scientist of the Day last summer, but we focused there on his successful efforts to persuade Yale to acquire the Revolutionary War paintings of John Trumbull, in the process inventing the charitable gift annuity. We mentioned then that Silliman was an early student and collector of meteorites, but pursued it no further.

Meteorites were a hot item at the time in geological circles, for only in 1803 had it been documented, in France, that stones actually do fall from the sky, and there had never been a documented meteor fall in North America. So Silliman was eager to document this one. The witnesses were cooperative, but most of the fragments were tiny. Silliman heard tales of a large chunk that had fallen and searched for it in vain. But the large stone did exist. The farmer who found it sold it to George Gibbs.

Gibbs was a Rhode Island businessman, the latest in a line of wealthy merchants; he had been smitten by minerals on a trip to Europe and became an avid collector. He bought two large collections overseas and brought them back to his home in Newport, where he continued to collect. It is not known how he made it to Weston in 1807 and acquired his prize possession before Silliman could even find it. But a magnificent specimen it was - a 36-pound chunk of meteoric iron. It became the prize of his Newport collection.

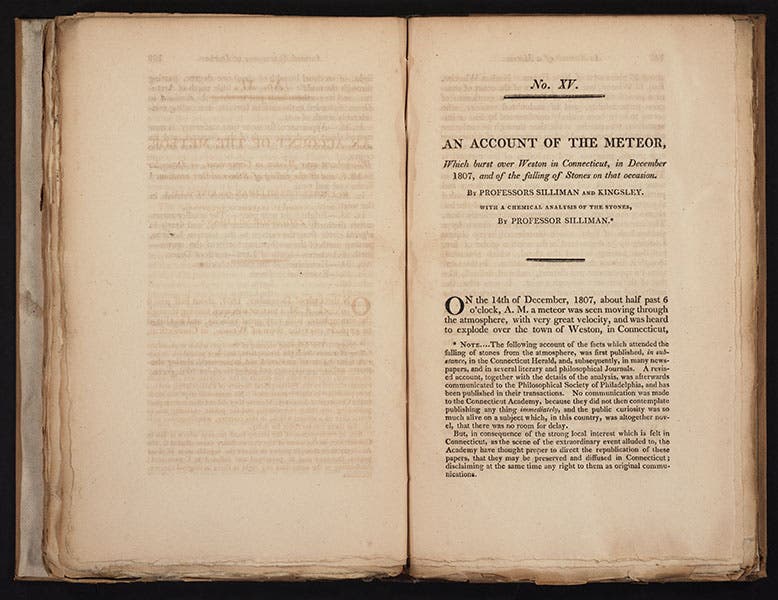

Silliman was unfazed - Yale did not yet have a mineral and meteorite collection - and he wrote several accounts of the Weston event and undertook a chemical study of the fragments he did have. He published the results in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society in 1809 and in the Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Science in 1810. We have both of these, but the second is more interesting, because the young Connecticut Academy had just launched its first journal, and Silliman's paper, "An account of the meteor which burst over Weston in Connecticut, in December 1807, and of the falling of Stones on that occasion" was published in volume 1 of the Memoirs. We show you the opening page (second image).

Silliman did one other very smart thing - he befriended Gibbs. The two put on a small show of some of Gibbs' collection at Yale in 1811, and when Gibbs finally decided to sell his collection in 1825, Silliman was first in line. He helped raise the considerable sum of $20,000 to buy the 20,000-item collection (put that way, the price doesn't sound so bad - a dollar apiece), and the Weston meteorite came along with it. The acquisition marked the beginning of the Mineral and Meteorite Collection at Yale, which was instantly the foremost such collection in the United States. The Weston fragment, the foundation stone of the collection, is still on display at Yale's Peabody Museum (first image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.