Scientist of the Day - George Gamow

George Gamow, a Russian/American nuclear physicist, was born Mar. 4, 1904, in Odessa (then in Russia, now in Ukraine). He studied in Leningrad until 1929, and was one of the discoverers of what is now called quantum tunnelling, whereby a particle can (metaphorically) “tunnel” out of a nucleus, even though it does not have the energy to do so, because of certain quantum effects, such as Heisenbeg’s uncertainty principle which allows a particle to have more energy than it should for a very small moment of time. Gamow went to Copenhagen to study with Niels Bohr, as did most of the other quantum revolutionaries. However, the Russian government refused to allow Gamow to return to Copenhagen in 1932. For some odd reason, they did allow him to attend the Solvay Conference in Brussels in 1933, and even more strangely, he was allowed to take his wife along. Gamow seized the opportunity and did not return to his homeland, instead opting to move to the United States in 1934, where he accepted a position at George Washington University. He taught there for the next 20 years.

Gamow is best known for being one of the “fathers” of the Big Bang theory, and for publishing a joint paper in 1948 which suggested that the 92 elements were “cooked” into existence in a primordial cosmic explosion. We have published one post on Gamow, but, for reasons that escape me now, I wrote there about his other career as a popular science writer and illustrator, an avocation at which he was extraordinarily good, producing books that had a profound influence on my own intellectual development. We have alluded to Gamow’s contribution to Big Bang Cosmology in other posts, and reproduced the first paragraph of his famous “alpha-beta-gamma” paper several times, but we have never put Gamow and the Big Bang paper up front under his own name. Today we will do just that.

We provided some background to the genesis of Big Bang cosmology in our post on Georges Lemaître, whom many consider the true father of the Big Bang. After Edwin Hubble discovered that the visible universe is expanding, cosmologists wanted to understand why, and one way to do this was to have the cosmos explode out of nothing, which would explain why everything is rushing away from everything else. Lemaitre proposed this in 1927, even before Hubble announced the expansion. Gamow's idea was to use the 92 elements that make up our universe as evidence for a Big Bang, by showing that they could be built up from hydrogen and helium during the Big Bang itself, when temperatures and densities were extraordinarily high, and only under such conditions.

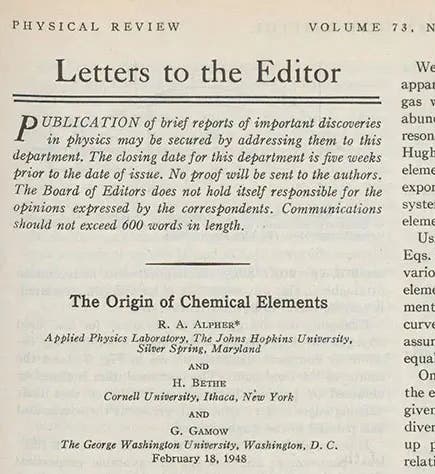

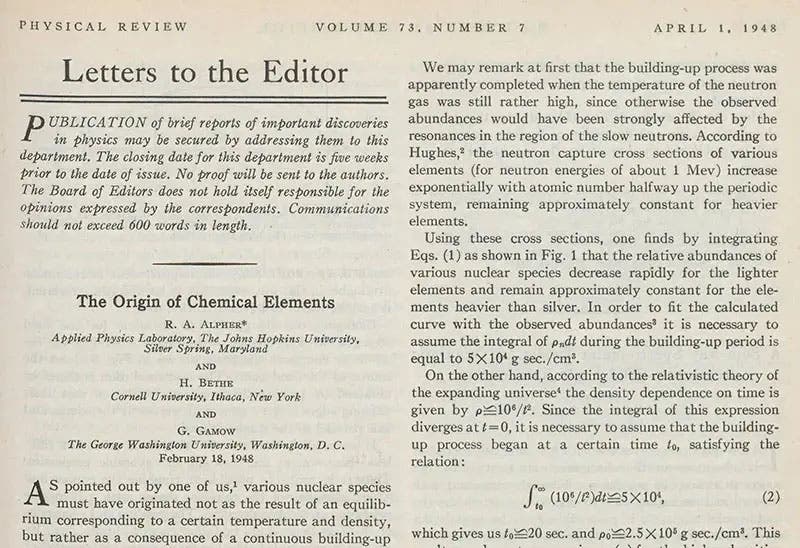

Gamow worked out his theory of nucleosynthesis with a graduate student, Ralph Alpher, but before he sent the resulting paper out to the editors of Physical Review, it occurred to the puckish Gamow that their two-author paper, written by physicists whose names sound like "alpha" and "gamma," would be amusingly enriched if they could add an author whose name sounded like " beta." As fortune would have it, Hans Bethe was a gifted young physicist now teaching at Cornell, and so Gamow added Bethe as third author and arranged the author list in Alpher-Bethe-Gamow order. The paper was published that way (on April 1, to boot), and it has been known as the “alpha-beta-gamma” paper ever since (first image). Hans Bethe was tickled to death to be included, but Ralph Alpher was not at all pleased to now be third fiddle, even if his name came first.

The irony was that the theory of nucleosynthesis worked out by Gamow and Alpher in their paper was mostly wrong, because of an unrecognized energy barrier that prevents elements heavier than beryllium from forming under Big Bang conditions. It took proponents of a rival cosmology, the Steady State theory, led by Fred Hoyle, to come up with a better explanation for the origin of the elements, arguing that hydrogen and helium are indeed primordial, but everything else is fused together in the cores of stars and in supernova explosions.

Gamow moved on to the University of California at Berkeley in 1954, and then, just two years later, to the University of Colorado at Boulder, where he worked on, of all things, deciphering the genetic code. He died on Aug. 19, 1968, and was buried in a cemetery there (last image). I like the idea of including a memorial bench at a gravesite. One doesn’t see that nearly enough.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.