Scientist of the Day - George Field

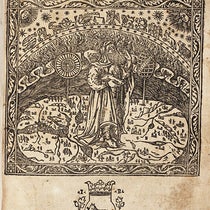

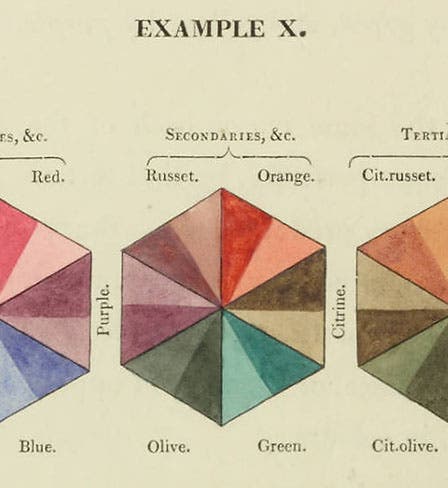

George Field, an English chemist, color theorist, and purveyor of pigments, died Sep. 28, 1854, at about age 77; his date of birth is unknown. Field wrote two books on color. The first, called Chromatics, or, an Essay on the Analogy and Harmony of Colours (1817), is mostly theoretical. He distinguishes and defines the primary, secondary, and tertiary colors, with handsome hand-colored diagrams setting out the combinations (first image). He even suggests in this book, like several authors before him, that there is a strong analogy between the spectrum of colors and the scale of musical tones, so that one can have chords of colors that are either consonant or dissonant (second image). This first book is quite scarce and very attractive; we bought the copy in our collections from bookseller Charles Wood in 2012.

The other book by Field in our collections is called Chromatography; or, a Treatise on Colours and Pigments, and of their Powers in Painting, London (1835). This work is much more common, being reprinted and translated many times. It has a more practical basis, with the focus on pigments and how they are made, and extensive discussion about which pigments are stable and suitable for artists, and which are not. Field made and sold pigments himself, inventing quite a few new ones, and he did extensive studies on their durability over time. He comments on each individual pigment and its advantages and drawbacks, and then provides a series of tables – those pigments that change under the action of light, those that change when subjected to various gases, those that suffer when mixed with metallic paints, and those that are stable under most conditions. An artist could earn a great deal about pigment use from Field's book.

Historians have evaluated Field as a color theorist and concluded that he came up rather short in that department. He never really understood the difference between mixing colors of light and combining colored pigments, so that he rejected Newton's discovery that white light is a combination of all the colors. But as a pigment maker and tester, he was very influential. All those brilliant reds and flame oranges that J.M.W. Turner used in his sensational paintings, such as The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons (ca 1835) – they all came from Field. The two knew each other well and consulted frequently. Field even invented an "orange vermillion" that Turner used extensively, and whose secret recipe Field never divulged, so the pigment died with him. Tuner seems to have paid attention to Field's advice about which colors would last and which would not. There was a pigment made from the newly discovered element iodine that was all the rage, a mercuric iodide that was called “iodine scarlet.” Field cautioned against using it:

The charms of beauty and novelty have recommended it, particularly to amateurs; and its dazzling brilliancy might render it valuable for high and fiery effects of colour, if any mode of securing it from change should be devised; but it is out of the general scale of nature – at any rate it should be used pure or alone, but in the recency of experience it ought not to be trusted by the artist.

Turner heeded Field’s advice and did not use iodine scarlet in his paintings; those that did learned to regret it. We should give thanks to Field that the colors in most of Turner’s paintings have held up relatively well over the past 180 years.

The mezzotint portrait by David Lucas, after a drawing by Richard Rothwell, is in the National Portrait Gallery, London. Both of Field’s books in our collections are available online: Chromatics (1817), and Chromotography (1835).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)