Scientist of the Day - George Elliot

George Elliot, an English manufacturer, was born Mar. 18, 1814. Elliot lived out a classic rags-to-riches story. His father worked in a coal mine (a colliery, as the English call it) in Durham, and George started working there as a boy, assisting the miners. He managed to learn surveying, and a little about mine engineering, became a foreman, and then moved up into colliery management. By the time he was 26, he owned his first colliery, and he soon acquired more. He would continue to acquire mines throughout his life, amassing quite a fortune. But that is not the story we tell today.

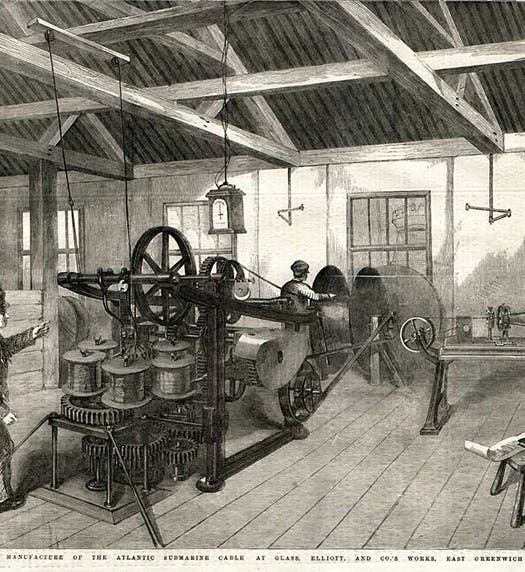

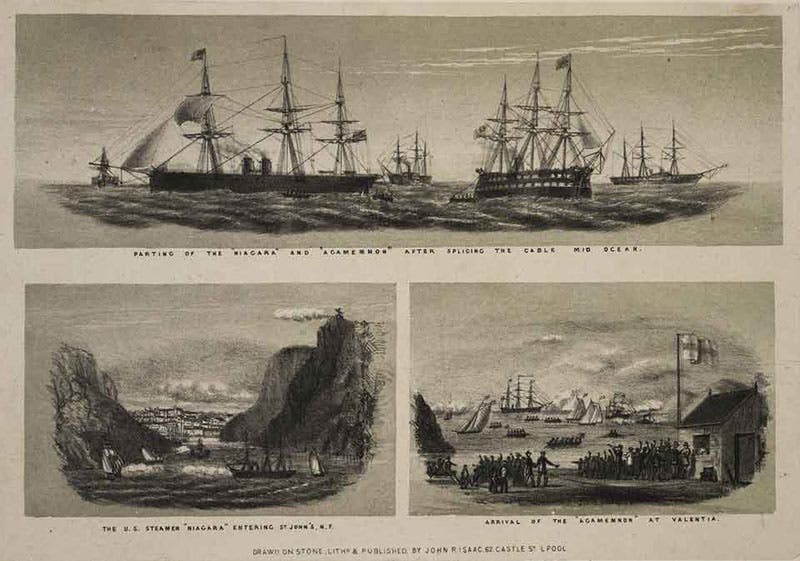

When Elliot was 35, he and a friend, Richard Glass, decided to buy a company that manufactured wire rope. They had no particular interest in wire rope, but the company was failing, the price was right, and they thought they could rescue the company and make a handsome profit. They renamed the firm: Glass, Elliot, and Company, and no sooner had they put the company back on its feet, than some investors from America, led by one Cyrus Field, began casting about for someone who could fabricate a submarine telegraph cable. Such a cable would have a copper core, to conduct the signal, surrounded by something to insulate the conductor, which had to be further surrounded by woven wire rope to give it strength.

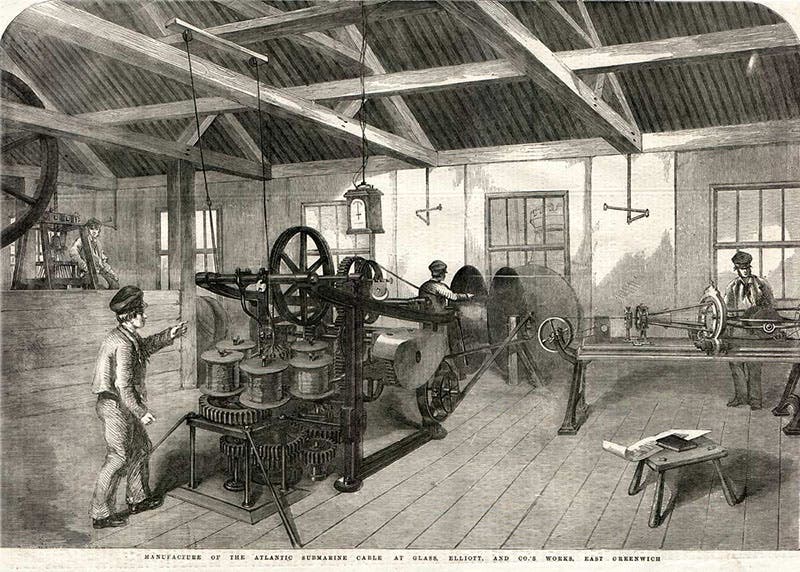

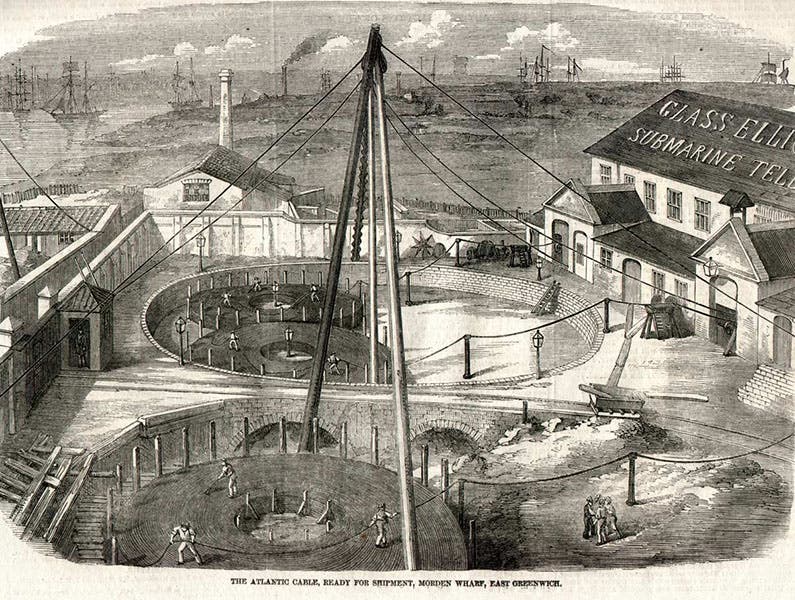

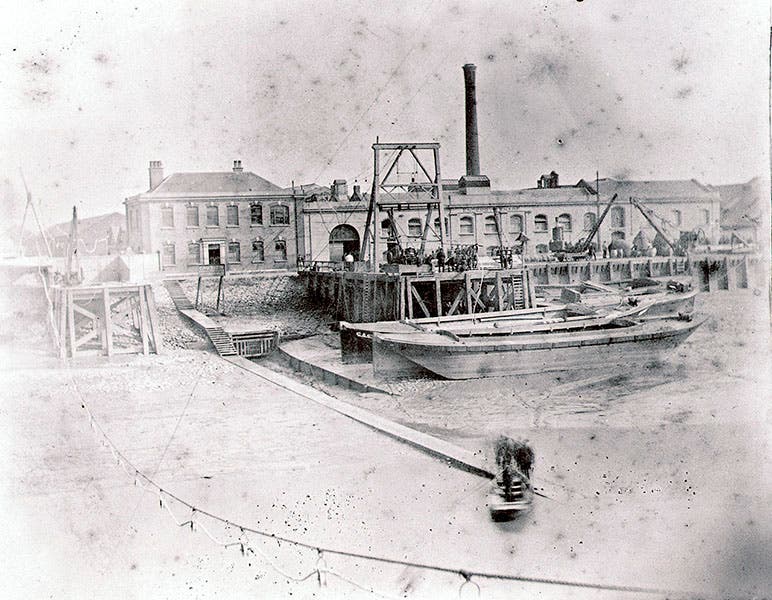

Glass and Elliot now knew how to make wire rope, so all they had to do was find partners who could make the conducting cable. Gutta-percha, a rubber-like resin from India, had recently emerged as a candidate for a flexible insulator, and before long the technology to manufacture a sturdy submarine cable had emerged. When the first attempt was made to lay an Atlantic Cable in 1858, Glass and Elliot got the contract to supply half of the cable, some 1200 nautical miles worth. I presume they supplied the part that ran from mid-Atlantic to Ireland. The 1858 cable worked for only a brief while, and then failed, through no fault of Glass and Elliot – it turned out that one of the engineers had fried the cable by using too strong an electrical signal to test it.

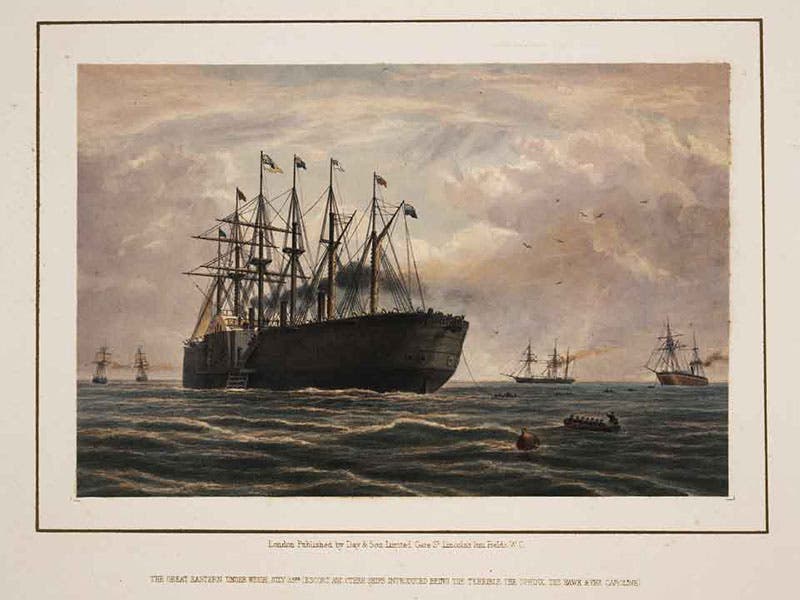

Glass, Elliot, and Co. subsequently merged with the Gutta Percha Company to form the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, and they were awarded the bid to supply the entire cable for the next attempt, which was in 1865. That cable, laid by the mammoth Great Eastern built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, broke in mid-Atlantic, but the next year, 1866, a new cable was laid successfully, and the Great Eastern then went back and retrieved the end of the broken 1865 cable and completed it, so in effect they now had two transatlantic cables, and both worked, and kept working. And it was all Glass and Elliot cable.

The transatlantic cable efforts were visually well documented. The Illustrated London News (ILN) ran regular stories during the lead-up to the 1858 attempt; we show several of their wood engravings here (from an intermediary source – we do not, unfortunately have a run of the ILN). A book illustrated with tinted lithographs, by John Isaac, which is in our collection, then documented the 1858 enterprise (third image), and an even more sumptuous volume, also in our library, illustrated the 1865-66 enterprise; it was written by William H. Russell, with chromolithographs by Robert Dudley, and captured every stage of the cable-laying process (fourth image).

Someone has prepared a display case that shows sections of the various cables that were laid in 1858, 1865, and 1866). We found a photograph of the case (sixth image) on the very rich and valuable website, atlantic-cable.com (which also supplied us with our ILN wood engravings). Each cable came in two thicknesses: a thick, heavy one, used on the shore and the continental shelf, and a thinner one that stretched across the Atlantic Ocean floor. At the top, one can see cross-sections of each cable; the evidence suggests that Elliot and Glass had learned their craft well.

Elliot returned to running his string of mines, then became a member of Parliament, and along the way, he acquired a knighthood, and a baronetcy. He became so well known that Vanity Fair had no qualms about allowing Leslie Ward (“Spy”) to caricature Sir George in an 1879 issue (seventh image). The cartoon is captioned “Geordie,” the name by which Sir George was known his entire life. We hope there is a good likeness at the core of this caricature, for we have no other portrait of Geordie.

If you are interested in other aspects of the laying of the transatlantic cable, you might consult previous posts on Cyrus Field, Charles Bright, Matthew Fontain Maury, and John Frederick Daniell. We have also published a post about the Vanity Fair caricaturist, Leslie Ward.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.