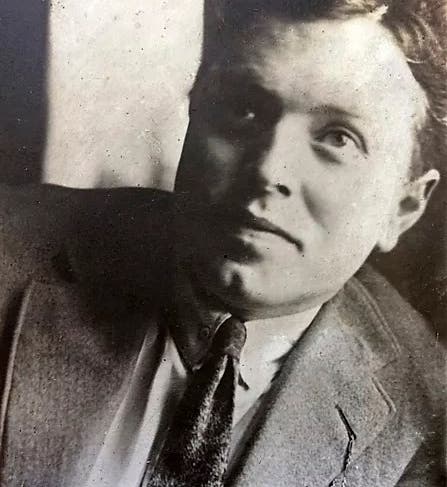

Scientist of the Day - George Eliava

George (Giorgi) Eliava, a Georgian microbiologist, was born Jan. 13, 1892, in Sachkhere in west Georgia, then part of the Russian Empire. He studied at Novorossiya University (now Odessa National University, in Ukraine), in Geneva, and then in Moscow, graduating in 1916. In 1917, he moved to Tbilisi, the capital city of Georgia, to take charge of a bacteriological laboratory (see map, second image).

A key time in Eliava’s life came in 1918-21, when he travelled to Paris to work at the Pasteur Institute. There he met Felix d’Herelle, who in 1917 had discovered bacteriophages, or phages as they are now called. Phages, as their full name indicates, “eat” bacteria, which is a bit of a misnomer, since phages have no digestive systems. We now know that phages are viruses, but all d’Herelle knew was that they killed bacteria, and each kind of phage was very particular about its dinner, preying on one and only one species of bacteria. In the 1920s, there was no arsenal at all in the war on microbial diseases, and d’Herelle thought that phages might be the weapon bacteriologists were seeking. He would mix up “cocktails” of different phages to be given orally to patients as a kind of phage therapy against bacterial diseases. And it seemed to work on many patients.

Eliava returned to Tbilisi in 1921 as a convert to phage therapy i, and he set up a new Institute of Bacteriology in Tbilisi in 1923 to pursue the study of phages and promote phage therapy. He came to believe that phages are living entities long before they were discovered to be viruses. He went back to Paris for a second period, 1925-27, and he subsequently invited d’Herelle to spend 18 months at the Tbilisi Institute in the early 1930s in a kind of exchange. D’Herelle was so impressed by Eliava and the Institute that he made plans to move there, and the Institute built him a special “French cottage” on the grounds. But it was not to be, because of the onslaught of Stalin’s Great Terror in 1937.

Eliava (along with his wife, a prominent Georgian opera singer) was arrested in the spring of 1937 and charged with being an enemy of the state. He was accused of spying on the Russian Red Army, selling secrets to the French, and even of waging covert bacteriological warfare. He was convicted and executed on July 9, 1937; he was 45 years old. It is often related that Eliava was targeted because he carried on with a woman who had attracted the fancy of Lavrentiy Beria, a political boss in Georgia and soon to be Stalin’s Commissar of the Soviet Secret Police. There seems to be no evidence for this, and the fact is that Beria engineered the arrest of some 30,000 Georgians and the execution of over 14,000 of them during the Great Terror, and it is doubtful that all or even any of these can be attributed to Beria’s habits as a sexual predator, although he certainly was that.

After Eliava’s death, the Bacteriological Institute continued on, although phage therapy fell in popularity when the first antibiotic, penicillin, was discovered and mass-produced during the Second World War. Antibiotics are much less picky about their targets than bacteriophages, and easier to administer. For the next fifty years, phage therapy was a medical footnote, except in Georgia. But then superbugs, resistant to a variety of antibiotics, began to appear in greater numbers, and phage therapy, as an alternative to antibiotics, is of interest once again, and the Tbilisi Institute, renamed the George Eliava Institute of Bacteriophages, Microbiology and Virology in 1988, is at the forefront of modern phage therapy research. The New York Times Magazine ran a lengthy story in 2000 on the Tbilisi Institute and its continued pursuit of phage therapy, even as the city was falling apart all around them, facing difficult economic times in the aftermath of the breakup of the Soviet Union.

After Elivia’s execution, all his papers and photographs were destroyed, and he was virtually unknown for forty years after his death. Fortunately, he was officially “rehabilitated,” and he is now honored, with d’Herelle, as one of the pioneers in the study of bacteriophages and the advancement of phage therapy in the treatment of microbial disease. If phage therapy continues to prosper, he will probably become even better known, even to the general public, and that would be a welcome historical development.

I have a post in progress on Felix d’Herelle, who inspired not only Geoge Eliava, but novelist Sinclair Lewis, who modelled the principal character in Arrowsmith (1925) on d’Herelle; that post should come to light in the near future. I should write one on Sinclair Lewis as well, since there are not many great novels with a scientist as protagonist.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)