Scientist of the Day - George Edwards

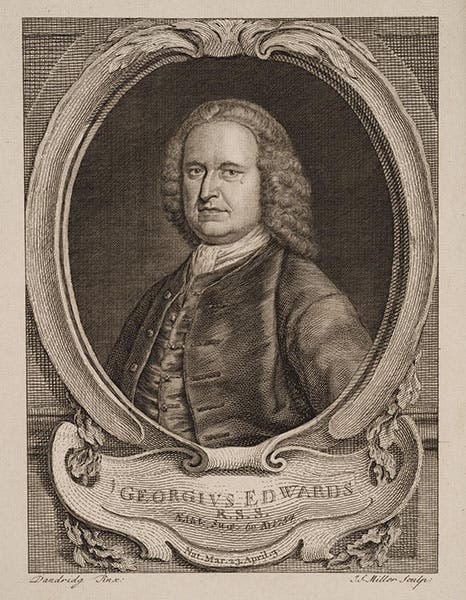

George Edwards, an English painter of birds, was born Apr. 3, 1694, in a hamlet in Essex. He spent some years travelling, then settled down in London in the 1730s to draw animals, especially birds. He became acquainted with Hans Sloane, who took him under his patronly wing, and with Mark Catesby, his senior by 11 years, who in 1729 published the first volume of his The Natural History of Carolina, Florida & the Bahama Islands. Edwards copied many of Catesby’s birds (for practice, not for publication), and he supposedly learned how to etch from Catesby. In order to provide Edwards with an income while he pursued his artistic calling, Sloane arranged for Edwards to be appointed "beadle" of the Royal College of Physicians in London, a common position in those days but one that has disappeared from most organizations and colleges nowadays. Edwards organized the meetings, sent out invitations, maintained records, and curated the society library, and for carrying out these duties he was given living quarters, a very modest salary, a chance to mingle with the elite of British scientific society, and plenty of free time to draw exotic birds and animals.

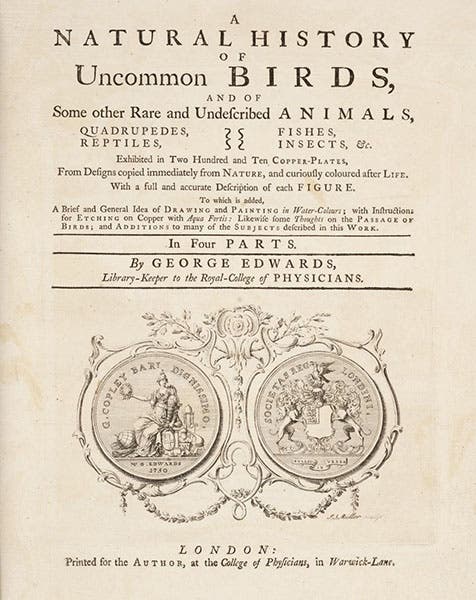

The first volume of Edwards’ Natural History of Uncommon Birds appeared in 1743, containing 52 hand-colored plates that he drew and etched himself, while overseeing the coloring. He turned out six more volumes over the next 21 years, the next three with the simpler title, A Natural History of Birds, and the last three with a new title: Gleanings of Natural History. The final volume appeared in 1764. Despite the changing titles, the 7 volumes are usually treated as a single set, with the title: A Natural History of Birds (1743-64).

Although we have a fine second edition of Catesby's work (the second edition, interestingly, was edited and published by Edwards in 1754, after Catesby's death), our library has never managed to acquire a set of Edwards’ Natural History, and given the high price that it commands on the rare book market, it seems unlikely we will ever get one, unless a donor comes out of the shadows. Fortunately, several institutions have made the complete work available online, such as the Library at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where you can find volume 1 at this link, and easy access to the other volumes from this page. All of the images we show here are taken from the Madison set. We include on this webpage the Grey-headed green woodpecker (first and fourth images), several Little Indian kingfishers (fifth image), a Whooping crane from Hudson's Bay (sixth image), and a "Speckled diver" (a loon), also from North America (seventh image). The detail of the Gray-headed green woodpecker (first image) allows you to appreciate Edwards’ etching technique, as well as the excellent hand-coloring.

Eighteenth-century bird illustration takes some getting used to – the birds are a bit stiff, since they were drawn primarily from stuffed specimens, and you don't get the same thrill – at least I don't – that one gets from bird illustrators of the next century, such as Edward Lear, Elizabeth Gould, and even the wood engraver Thomas Bewick. That said, collectors of ornithological books love Edwards, and even individual etchings extracted from his books can be expensive. And we should mention that while Edwards is now known as a bird painter, he did include in his volumes, especially the Gleanings, more than a few etchings of animals, fish, and reptiles, often including them in with the birds, Catesby-style.

An American plantation owner in North Carolina, John Drayton (who was the only American subscriber to A Natural History of Birds), acquired 48 watercolors that Edwards painted in 1733, ten years before his first volume was published. These watercolors disappeared for several centuries, only to turn up in the attic of a Drayton descendant in 1969. Drayton's plantation house, Drayton Hall, is northwest of Charleston, on the Ashely River, and is a National Historic Landmark, because of its Palladian design. Twenty-one of the original Edwards watercolors are now preserved there and are occasionally on display. We show you one, the Carolina Parakeet, which seems the appropriate choice (eighth image).

When he was 65 years old, Edwards sold his entire portfolio of paintings, plates, and prints, and claimed to be out of the business – this was after publishing volume 4, the intended final volume of his Natural History. But he kept drawing and etching, and the three volumes of Gleanings followed. I guess it is hard to retire from being an artist. Edwards died in 1773, well-esteemed and admired as one of the century's finest animal painters.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Speckled diver [loon], hand-colored etching, A Natural History of Birds, by George Edwards, vol. 3, pl. 146, 1750, University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries (search.library.wisc.edu](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/aee67a87-e174-4b84-a40e-3a0e122134db/edwards7.jpg?w=476&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)