Scientist of the Day - George Canning

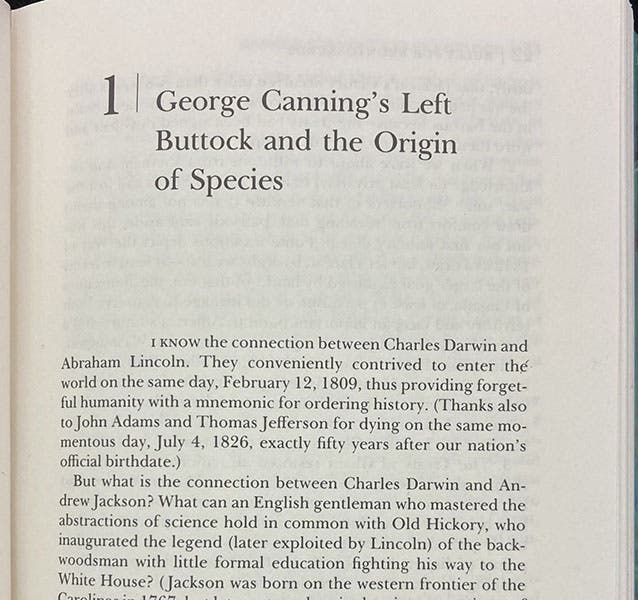

George Canning, a British politician, died Aug. 8, 1827, at age 57. In the 1980s, Stephen Jay Gould wrote an essay (originally appearing in Natural History magazine and republished in Bully for Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History, 1991) called "George Canning's left buttock and the Origin of Species", intended to demonstrate the contingency of evolution through a historical example. As the story was laid out, Lord Castlereagh, Britain’s war minister, outraged by some behind-the-scenes shenanigans of Canning, the foreign minister, challenged Canning to a duel (we are skipping the first part of the essay, which begins with Andrew Jackson and weaves its way to Castlereagh). The two men faced off on Putney Heath in southwest London on Sep. 21, 1809 (the year of Darwin's birth, a morsel I add to the story), and after missing first shots, the second shot of Canning struck a coat button of Castlereagh and left him unharmed, while Canning received a shot in his rear end (euphemistically called his “thigh” on Wikipedia).

Because Castlereagh survived this encounter, he lived until 1822, in which year, in a state of severe depression, he committed suicide. Castlereagh was the uncle of an officer in the Royal Navy named Robert Fitzroy, who, like his uncle, was prone to fits of depression. With the voyage of HMS Beagle impending, and because he feared that the isolation of a captain on the high seas would drive him to suicide as well, Fitzroy decided to invite a companion to join him on the Beagle voyage, someone of his own social standing without military rank, who could dine with Fitzroy and provide him with some social interaction. The man he invited on board was, of course, Charles Darwin, who was thus put on the road to the greatest discovery of the 19th century, evolution by natural selection.

Opening of chapter, “George Canning’s left buttock and the Origin of Species,” by Stephen Jay Gould, in his Bully for Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History, 1990 (author’s copy)

The point of Gould’s essay is that Canning's taking a bullet in his left cheek was, in a way, a causal element in Darwin's discovering the geographic diversity of species on the Beagle voyage; had Canning not lost the duel, Darwin, in all probability, would not have been invited on the Beagle voyage and would not have discovered evolution. Contingency plays a major role in history, as well as evolution. In my opinion, Gould was a little off in his attempt to connect the dots – it was not so important that Canning got shot in the butt as that Castlereagh got shot in the button – but the point is still well taken: evolution is the result of chance events, and one little impacting asteroid here, or volcanic eruption there, can lead to cascading events that could completely change the faunal and floral population of our planet. Indeed, this has happened more than a few times.

Canning, incidentally, survived Castlereagh, became Prime Minister in 1827, and then died after only 119 days in office. He is usually described as the Prime Minister with the shortest tenure in British history, but he should be described as the only Prime Minister who took one in the rear for Darwin’s theory of evolution.

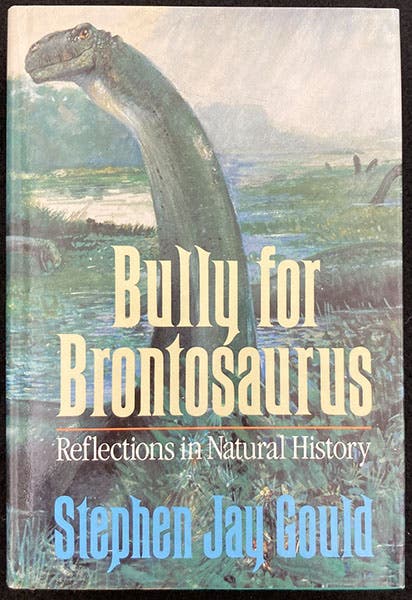

Dust jacket of Bully for Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History, by Stephen Jay Gould, W.E. Norton & Co., 1991 (author’s copy)

Gould’s book contains another famous essay that gave its title to the book, in which he argued that there is nothing wrong with referring to Brontosaurus by that name, since it has such a venerable history, even if the correct scientific name is Apatosaurus. My five-year-old grandson, who knows both names, thoroughly agrees. There is also in the book a great essay, number 10 of 35, called “The case of the creeping fox terrier clone,” in which Gould wonders, quite appropriately, why the ancestral horse, Eohippus, is invariably described in textbooks as being the size of a fox terrier, and not, say, a whippet, or a bobcat. What follows is a wonderful diatribe on the derivative nature of modern textbooks. Gould’s essays drive me to distraction sometimes, with his continual erection of straw men that he likes to pull down, but most of his essays have a good point to make about either evolution or human folly, and he is still well worth reading. Bully for Brontosaurus is an excellent place to start.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Bivouac on Jan. 26 [1854], chromolithograph from a sketch by Balduin Möllhausen, Explorations and Surveys for a Railroad Route from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean: Route near the Thirty-Fifth Parallel, by Amiel W. Whipple (Pacific Railroad Report, 3), 1856 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/55140a90-4b5d-4dac-832c-5def5cb51a10/Whipple1_cover.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)