Scientist of the Day - Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, a German philosopher, was born Aug. 27, 1770. Hegel was one of the foremost figures of the philosophical school known as German Idealism, which would put him beyond the pale of this series, but a treatise that he completed in 1801 was actually on the structure of the solar system, providing us a welcome loophole. Hegel's treatise was what German educators call an inaugural dissertation, written as part of an application for a position at the University of Jena, where his friend Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling was already a professor. It was called Dissertatio philosophica de orbitiis planetarum (Philosophical Dissertation on the Orbits of Planets, 1801), and its subject was the number and spacing of the planets in the solar system, the very problem that Johannes Kepler had wrestled with in his first treatise 200 years earlier. In particular, Hegel considered whether there might be an as-yet-unknown planet between Mars and Jupiter, as some astronomers had predicted. Hegel argued that there was no reason to believe a planet was there, just months before Giuseppe Piazzi discovered the first asteroid, Ceres, in that very region (first image).

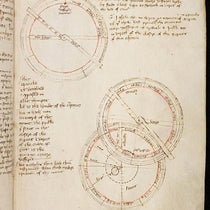

Historians of astronomy have long poked fun at Hegel for his ill-timed dissertation. After several generations of critics had ridiculed Hegel for his a priori reasoning, two scholars did what someone should have done long before – they carefully read Hegel's thesis. And they discovered that Hegel was much more clever than anyone thought (well, more clever than historians thought – philosophers already knew he was fairly astute). What Hegel had actually done was to attack was the evidence then being offered for the existence of a planet in the Mars-Jupiter gap. A mathematician named Bode (and another named Titius) had constructed a numerical sequence, generated by a simple rule and yielding this series: 4, 7, 10, 16, 28, 52, 100, 196, etc. Now if you consider the Earth's distance from the Sun to be 10 units, then the Bode-Titius law predicts the distance of each planet from the sun: Mercury is 4, Venus is 7, Earth is 10, Mars is 16, Jupiter is 52, and Saturn 100. Note that two of the numbers in the Bode-Titius series do not correspond to planets: 28 and 196. But in 1781, the planet Uranus was discovered, and its solar distance was just about 196 units. So naturally, many astronomers predicted that there must also be an undiscovered planet between Mars and Jupiter, at distance 28. And so there was.

What Hegel did was to introduce an entirely different series, one that he found in Plato’s Timaeus. This numerical sequence predicted planets at all the known positions, but did not predict one at distance 28. Which sequence should one believe? Hegel was not trying to show that there can be no planet between Mars and Jupiter; he was rather demonstrating that arbitrary numerical progressions are not reliable predictors of anything. And he was absolutely right. The Bode-Titius “law” broke down completely when Neptune was discovered, which did not fit the sequence at all, and the law has been in disrepute ever since. So historians need to lay off Hegel – all he did was to note that the Emperor was naked, when all around him were admiring his outfit.

And we should point out that the dissertation accomplished its main function – Hegel got the job at Jena. And he never again attempted to roil the waters of astronomers.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.