Scientist of the Day - Georg Peurbach

Georg Peurbach, a German astronomer, was born May 30, 1423. In the medieval university, two texts were used to teach astronomy: The Sphere by Johannes de Sacrobosco, a basic introduction to the celestial and terrestrial spheres and their circles, and the Theory of the Planets, an anonymous work that provided an introduction to the epicycles and deferents that were used by the ancient astronomer Ptolemy in his great work, the Almagest. Peurbach taught at the University of Vienna, and in the 1450s he wrote a work that he called the New Theory of the Planets, which for the first time took the two-dimensional circular devices used by Ptolemy to account for planetary motion and fleshed them out into three-dimensional spheres that could be pictured by the non-mathematician. But Peurbach died in 1461, before he could publish his New Theory.

Fortunately, his younger colleague at Vienna, Regiomontanus, moved to Nuremberg around 1470 to establish a printing press devoted to mathematical science, and one of the books to come out of his shop before he himself died was Peurbach’s New Theory of The Planets (1474). The work became extremely popular as an introductory astronomical textbook in the half-century before Copernicus and for another half-century after that, and it went through many editions, usually printed right along with Sacrobosco’s Sphere. We do not have the Regiomontanus 1474 printing in our History of Science Collection – that is a very rare item – but we have the next edition of 1482 and a dozen others.

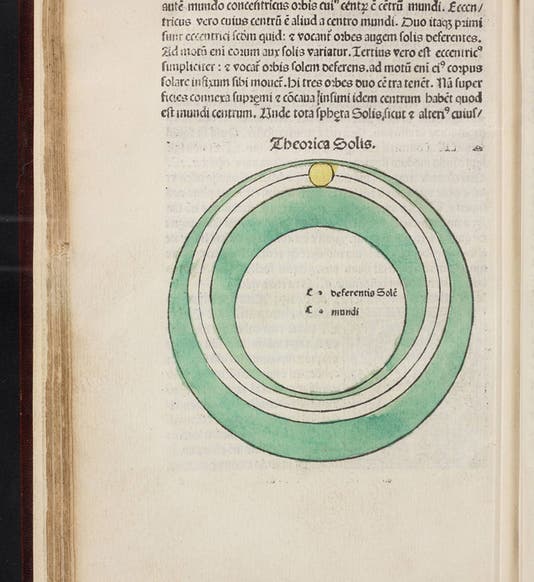

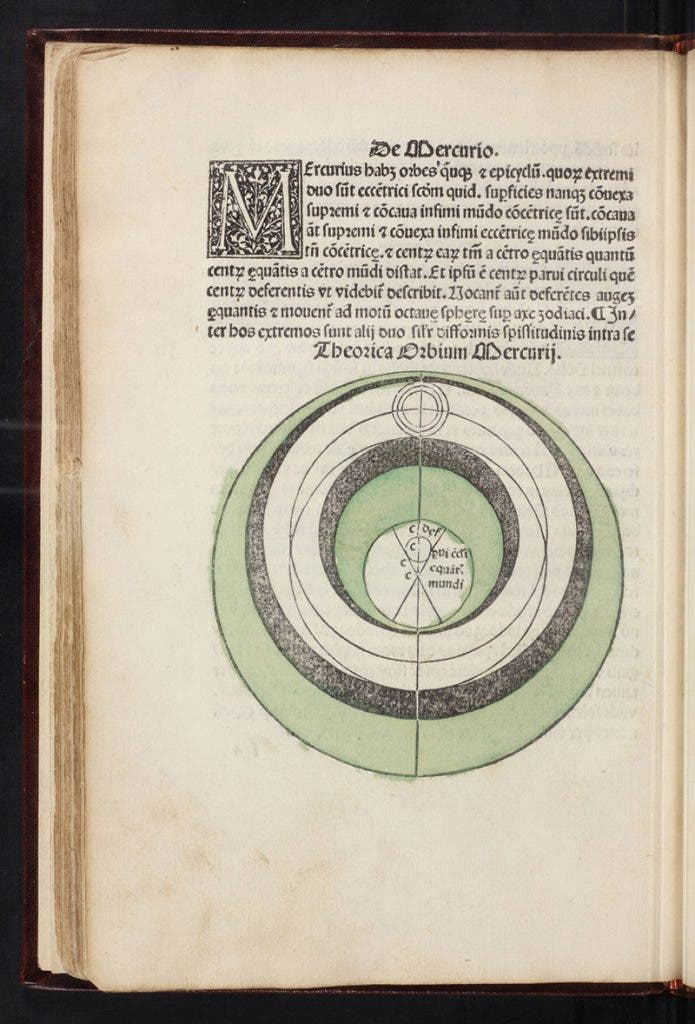

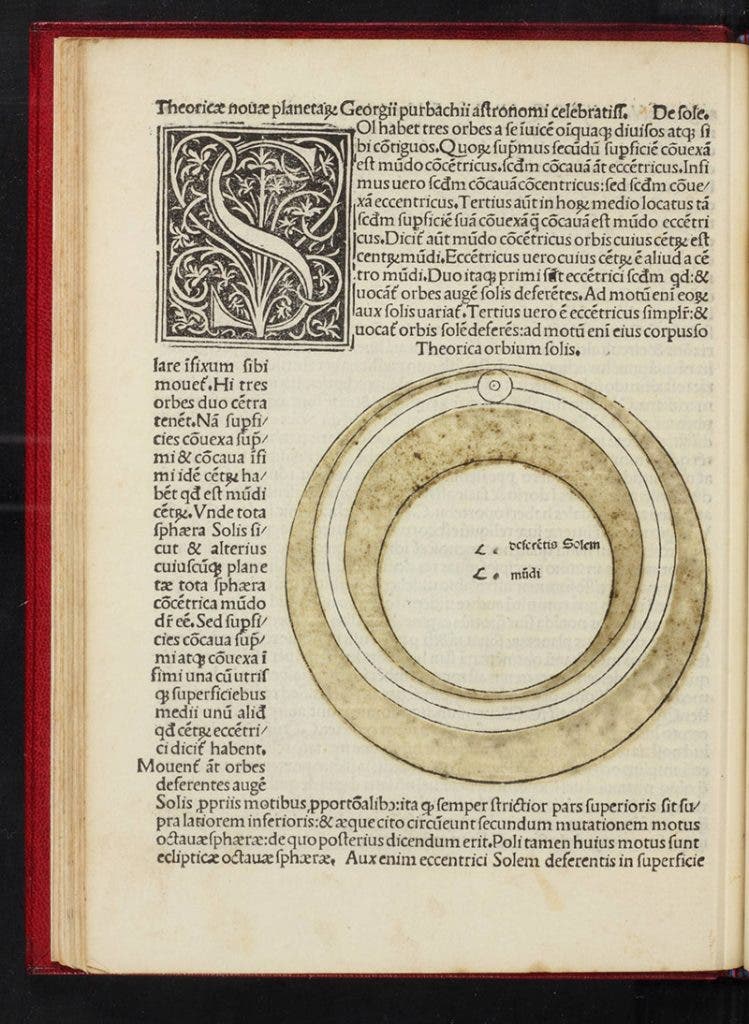

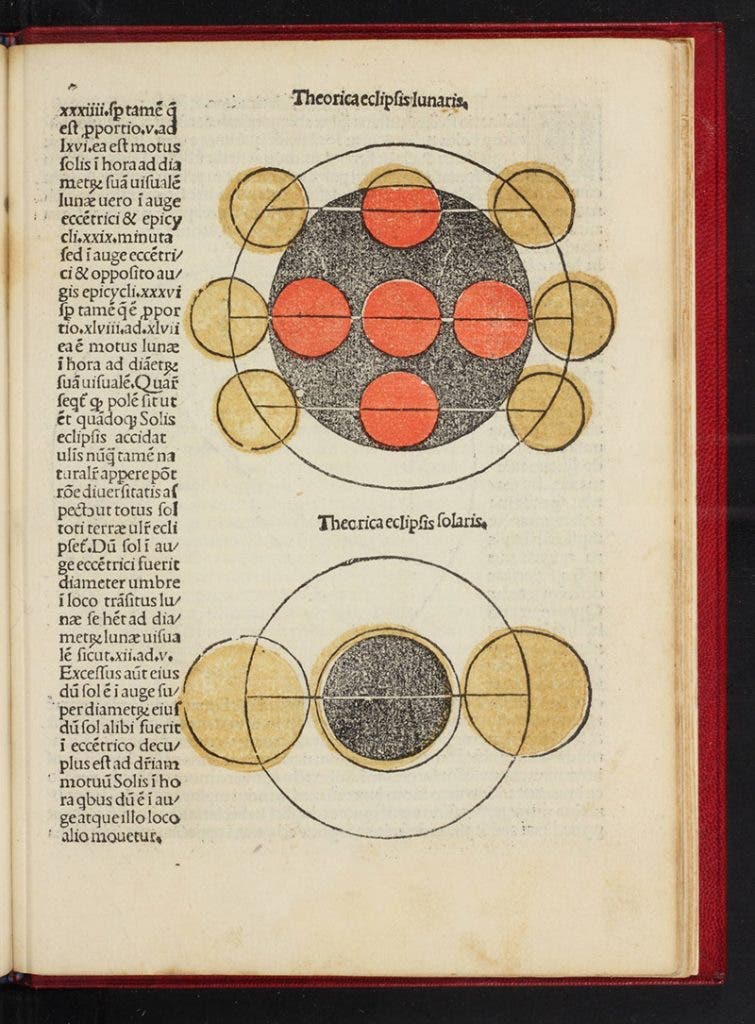

The early editions of Peurbach and Sacrobosco are also of interest to the historian of printing, because the diagrams of the solid spheres envisioned by Peurbach were among the first woodcuts to be colored—first by hand, and then by printing with additional blocks.

The images here show the orb of the Sun from the 1482 edition (hand-colored, first image), the orb of Mercury from the same edition (second image); the orb of the Sun from the 1490 edition (printed in color, and quite faded, third image); the orb of Mercury of 1490 (fourth image), and an illustration of lunar and solar eclipses from 1490 (fifth image). Notice how in this instance the block with the yellow color did not quite register with the blocks printing in black and in red.

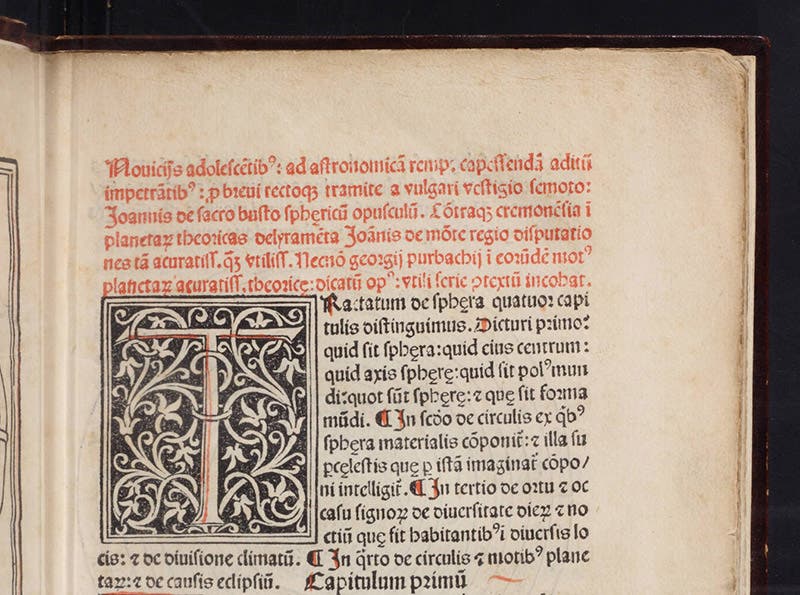

And since we have the book handy, we thought we would show you the problems one faces in trying to extract the title from a book printed in 1482, when books did not have separate title pages. Instead, the imprint information was crammed into the first few lines of the first page of text. Above is a detail of that section from the Sacrobosco Sphaera of 1482 (printed, incidentally, by Erhard Ratdolt in Augsburg), where you can make out, in the last two lines of red type, the name “georgii purbachii” and his book, “mot planetar acuratiss theorice”.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.