Scientist of the Day - Georg Christoph and Maria Clara Eimmart

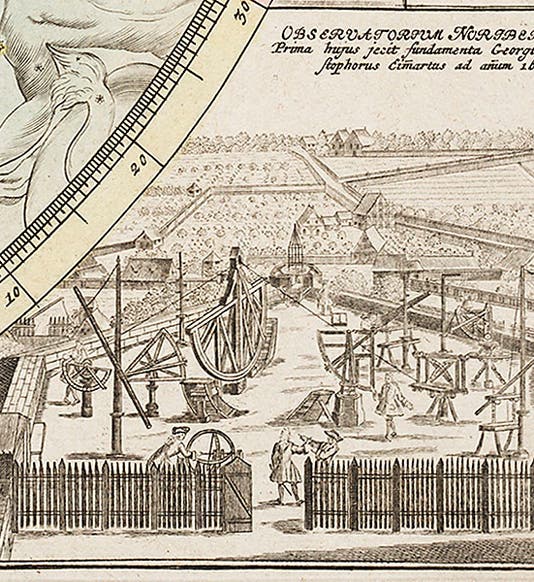

Georg Christoph Eimmart, a German astronomer and artist, was born Aug. 22, 1638. In 1678, Eimmart founded an astronomical observatory in the Vestnertorbastei, a garden area within a low wall just north of Nuremberg Castle. Unlike Tycho Brahe's pioneer observatory at Hven in Denmark, where each instrument was protected by a conical dome, Eimmart's observatory appears to have been an open-air affair. Several images survive of Eimmert's garden of sextants and transit circles; the one we have in our collection is an inset on a large star map that was included in Johann Doppelmayr's Atlas coelestis (1742; first image). Doppelmayr was a Nuremberger himself and was happy to showcase Eimmart's observatory, along with those at Greenwich, Paris, and Hven.

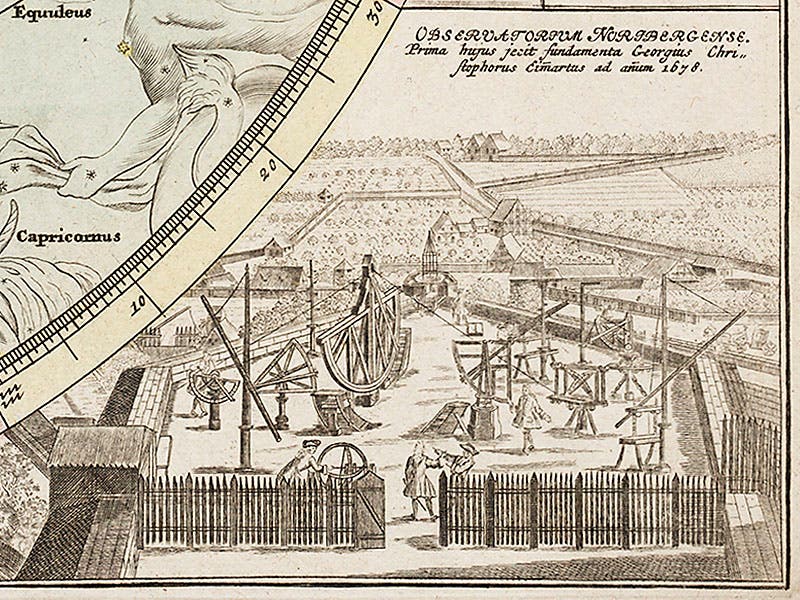

Being an artist and engraver, Eimmart was naturally drawn to the production of stellar and lunar maps. Most of the celestial planispheres that survive and bear his name were printed by others in the 18th century, especially by Johann Baptist Homann; there are a moderate number of these that survive, but we do not have a signed Eimmart celestial map in our Library. However, Doppelmayr's two celestial planispheres are credited to Homann (the northern planisphere is reproduced above, second image), and they look identical to the Homann maps by Eimmart, so we are guessing that we do have two Eimmart celestial planispheres in our collections after all.

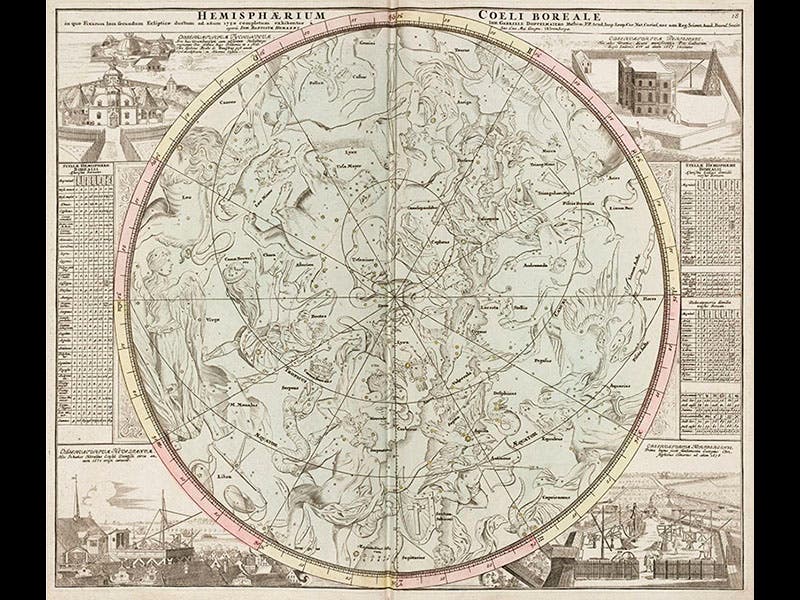

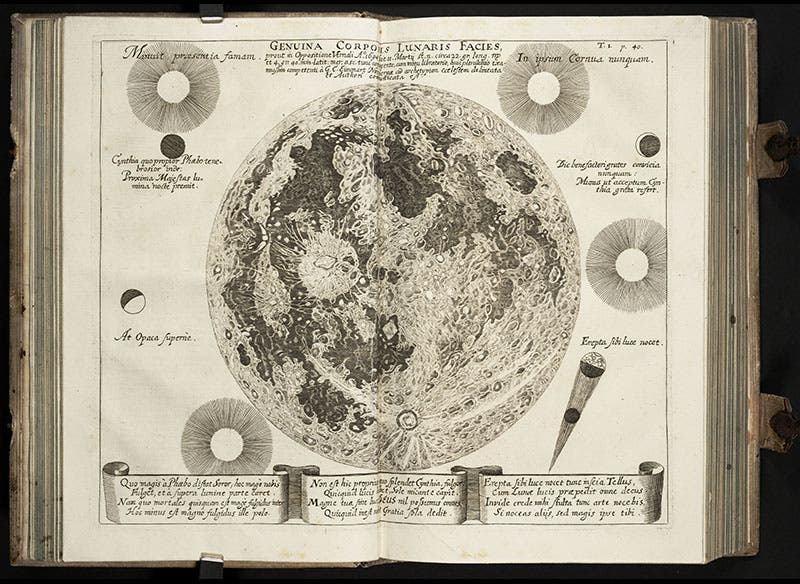

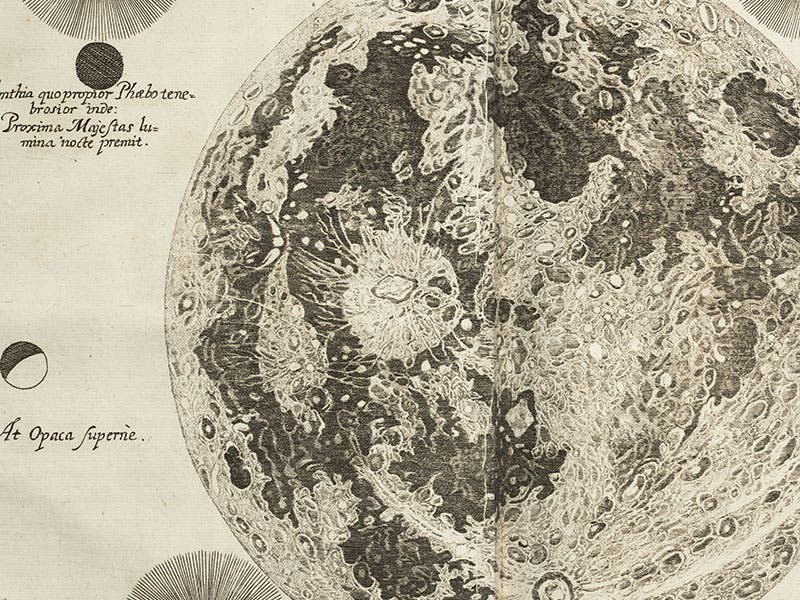

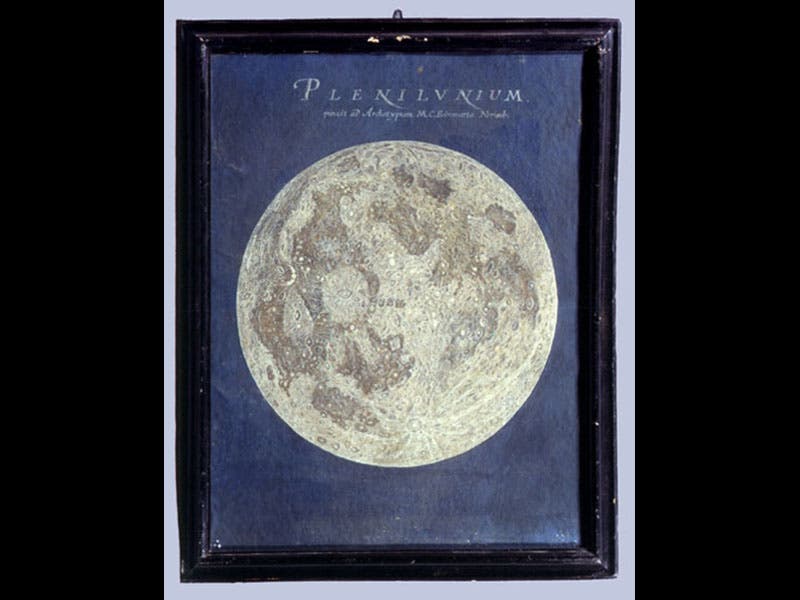

And we definitely have a moon map that bears Eimmart's name; it was published in a compendium by Johann Zahn, Specula physico-mathematico-historica (1696; third and fourth images). Like Doppelmayr's later atlas, this work was published in Eimmart's adopted home city of Nuremberg. The map is not a great one, from a technical point of view, since many of the lunar features are not in their proper places, and many others are completely missing. It is not nearly as accurate, for example as its two major predecessors, the lunar maps of Johannes Hevelius and Francesco Grimaldi/Giambattista Riccioli of 1647 and 1651 respectively. However, if one views the engraving as an impression of a full moon, rather than a map, then it quickly redeems itself. The Hevelius and Grimaldi maps are cold and dominated by line; they look nothing like the moon in the sky. The Eimmart map, on the other hand, shimmers, full of luster, and it gives a much better impression of what it is like to see the full moon rise after dusk.

That said, we must now determine just which Eimmart made this drawing. It has always been assumed that it was Georg Christoph, since he was a known engraver and artist and his name is on the map, and we presumed as much when we included Eimmart's moon in our exhibition, The Face of the Moon (1989). But it has recently been pointed out that the Bologna Observatory has a number of lovely drawings of the moon in its collection, including the spitting image of the printed Eimmart lunar map (fifth image), and their drawings are signed "M.C. Eimmart", indicating they were drawn by Georg's daughter, Maria Clara. It would not have been unusual for a scientific author and artist of the period to use the artistic output of his family in the production of maps and books and to give them no credit, and that appears to have been the case with Eimmart's moon map. Today, we would hope, Maria would receive her own byline.

There is a monument to Georg (but not Maria) that was recently erected on the site of his observatory outside Nuremberg Castle (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.