Scientist of the Day - Gaston Tissandier

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

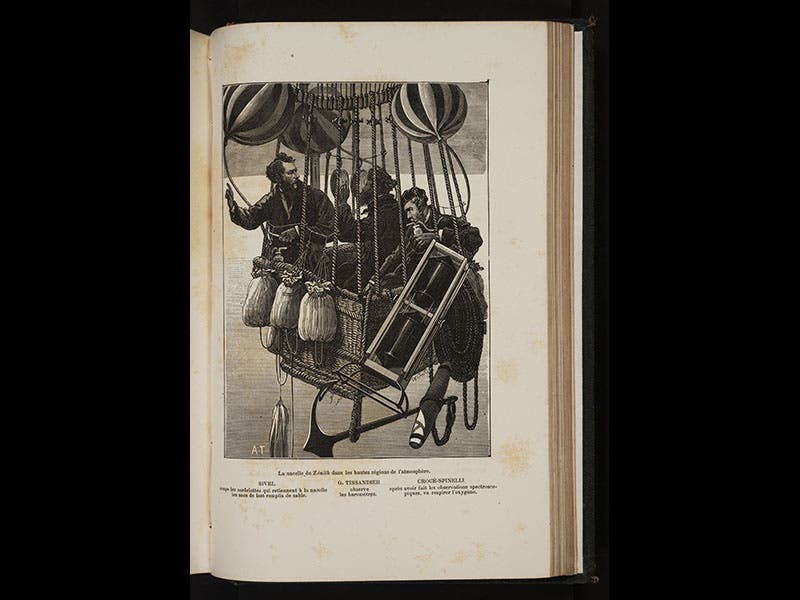

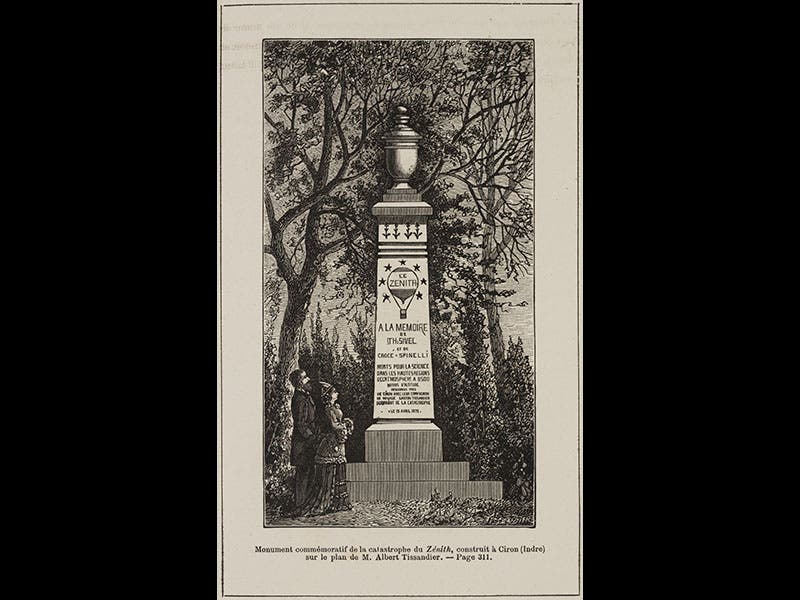

Gaston Tissandier, a French balloonist, was born Nov. 21, 1843. Tissandier made a number of high-altitude balloon ascents, beginning in 1868, and he often took along his brother Albert, a talented artist. Consequently,Tissandier's books (and he wrote quite a few) tend to have lively and accurate images, which is rare in this genre, as most balloon illustrations were made well after the fact, by artists who were often not even present. In 1875, Gaston attempted to wrest the high-altitude record from the English (who claimed to have ascended to 39,000 feet in 1862), and with two passengers, Joseph Croce-Spinelli and Theodore Sivel, he lifted off in the balloon Zenith on Apr. 15. They carried crude oxygen equipment, but in the excitement of rising above the clouds to around 29,000 feet, they forgot to use it, and the two passengers passed out in the rarefied air. They never recovered, and their deaths cast a considerable pall over the achievement, and to make it worse, they didn't even get the record.

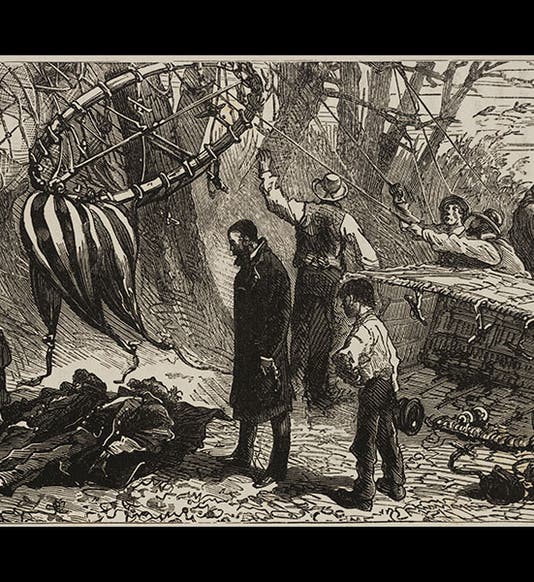

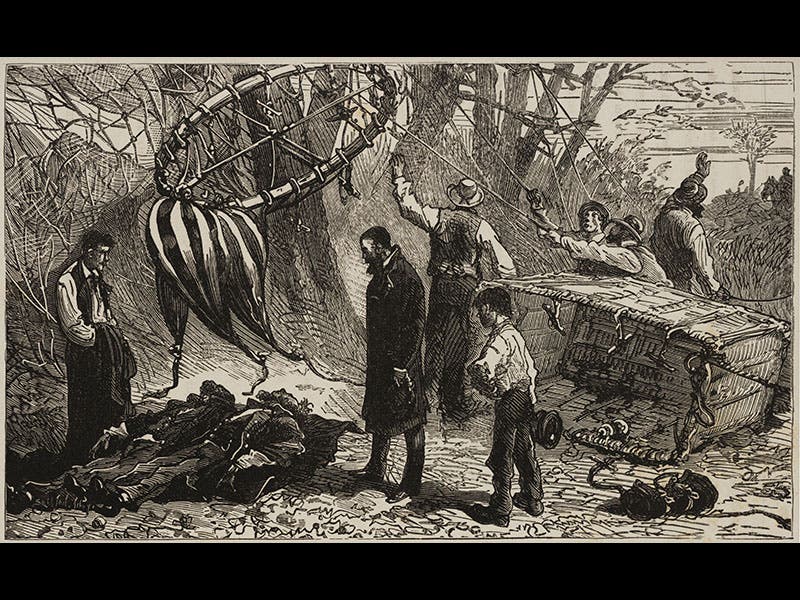

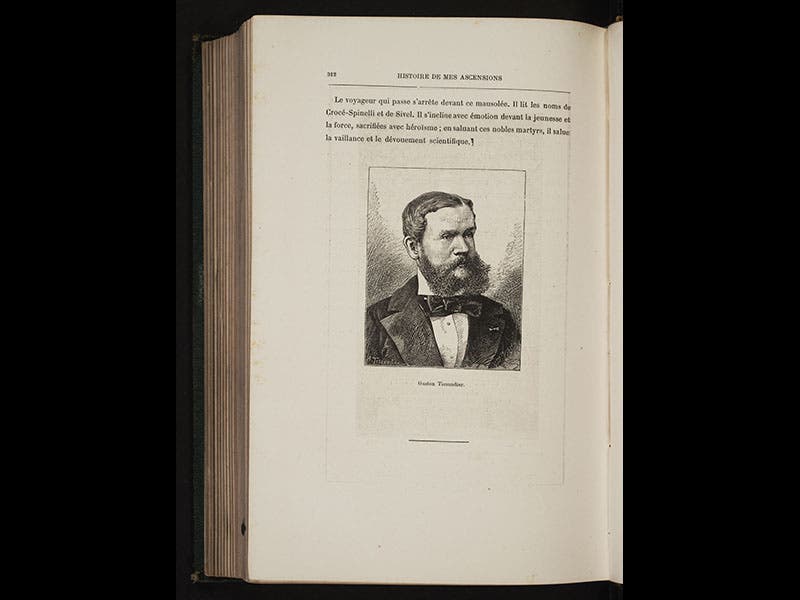

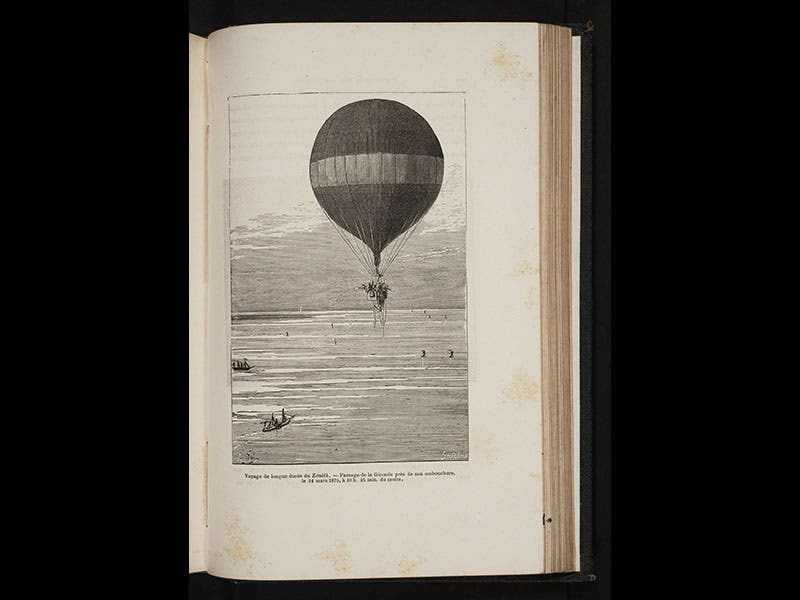

Albert Tissandier illustrated the tragedy in two of his brother's books, Histoire de mes ascensions, recit de vingt-quatre voyages aeriens (1878), and Histoire des ballons et des aéronautes célebre (1887-90), both of which we have in splendid copies in the History of Science Collection. The images above are all from the earlier Histoire de mes ascensions and show, in order: the Zenith after landing on Apr. 15, 1875, with the bodies of the two passengers on the ground; a portrait of Gaston by Albert; the Zenith on its previous voyage (called, because it lasted so long, the “voyage de longue durée”); the nacelle of the Zenith on the morning of the fateful flight, with (left to right), Sivel, Tissandier, and Croce-Spinelli aboard; and the monument erected at Ciron (Indre) to the high-altitude flight of the Zenith.

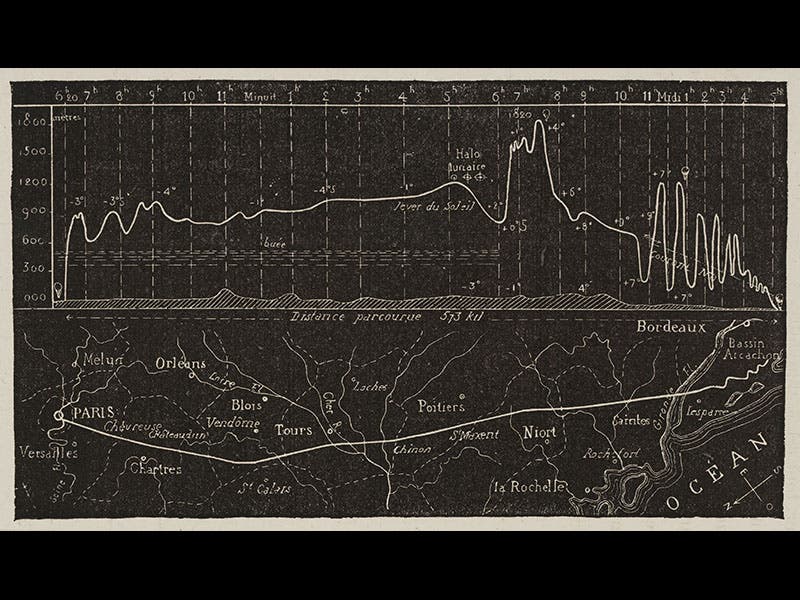

One of the interesting features of Histoire de mes ascensions are the white-on-black flight diagrams included for each of the 24 voyages. Each one has time as the horizontal coordinate, but the vertical one is multifold, including the changing altitude of the balloon, the height of the land over which they passed, and an aerial map of the country traversed. We show above the diagram for Tissandier’s voyage de longue durée, since it is especially rich (sixth image). I don’t believe that Edward Tufte included Tissandier’s book in his marvelous study of graphic design, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (1983) or any of his subsequent books, but he certainly could have.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.