Scientist of the Day - Gaspard Monge

Gaspard Monge, a French mathematician, was born May 9, 1746. His expertise was in descriptive geometry, a field that he invented, but he must have been a skilled administrator, for he was called upon to establish the École Polytechnique, where many engineers would be trained, and he also helped re-establish the Académie des Sciences, after it had been dissolved during the French Revolution, as the National Institute of France. And somehow, Monge befriended, or was befriended by, Napoleon Bonaparte, and he spent some time in Italy, helping set up the short-lived Republic of Rome after Napoleon had conquered that country. Perhaps it is not surprising that, when Napoleon in 1798 suddenly decided to invade Egypt with 40,000 soldiers in the van and 150 scientists following close behind, he chose Monge as one of the three scientific leaders to select and direct the activities of the savants. And when Napoleon established the Institute of Egypt, patterned after the National Institute of France, Monge was installed as its first President.

Monge should have had plenty to do, supervising the work of the young engineers. But he found an area of his own to investigate – a mystery, in fact. On the way down from Alexandria to Cairo, French soldiers had encountered desert mirages for the first time. They would see bodies of water in the distance, only to watch them dry up and disappear as they approached. Monge was intrigued. He knew it must be an optical effect, but the cause at first eluded him. Mirages had, indeed, resisted explanation since antiquity. Eventually Monge figured it out, and he was the first to do so. He reasoned that the sand of the desert must heat the air above it, so that the air forms layers, and these layers act as lenses, bending the light from the sky towards the viewer so that it looks like water in the distance.

Monge delivered his paper on mirages at an early meeting of the Institute of Egypt, and it was printed in the Mémoires sur l’Égypte, the new journal of the Institute, in 1800. It was one of the first scientific publications by any savant to come out of Egypt, as most of the other scientific work saw the light of day only in the Description de l'Égypte, which did not begin publication back in Paris until 1809. The Mémoires sur l’Égypte, incidentally, was printed with presses and type that Monge had commandeered from the Vatican, when he first heard about the Egyptian invasion while in Italy with Napoleon. We have a complete set of the Mémoires in our library.

Napoleon abandoned his savants in August of 1799 to return to France and establish himself as First Consul, and he took Monge with him. Monge returned to his post as Director of the École Polytechnique and accumulated numerous honors over the next few years, only to lose them all when Napoleon fell in 1814. When Monge died in 1818, he was buried in Pére Lachaise cemetery, but his reputation was later re-established, his remains were transferred to the Panthéon in Paris, and, when they chose 72 scientists to honor by placing their names around the Eiffel Tower, he was one of those selected.

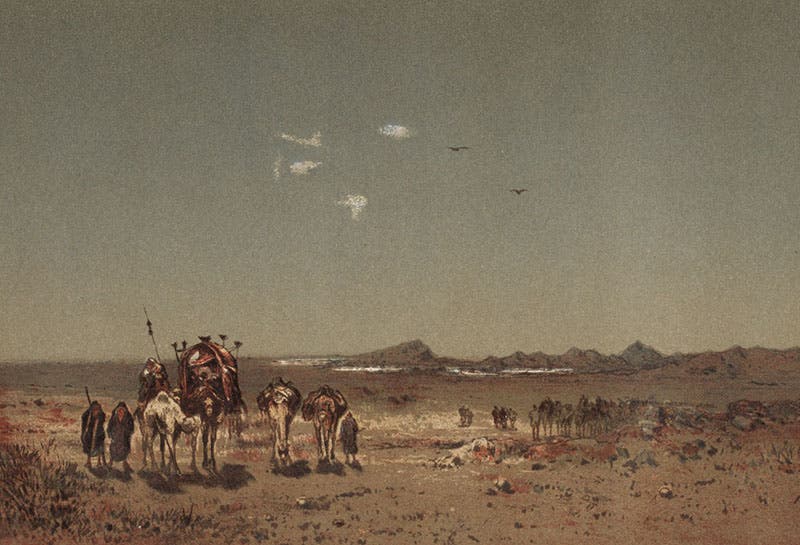

We included a discussion of Monge and mirages in our 2006 exhibition, Napoleon and the Scientific Expedition to Egypt. Although I was co-curator of the exhibition, the section on Monge was written by the other curator, Bruce Bradley, and I rely on his account here. The only view of a mirage that Mr. Bradley could find appeared 70 years later in a publication by Camille Flammarion (second image), and I was no more successful. Monge, teacher of descriptive geometry, should surely have provided his own visual description of a mirage.

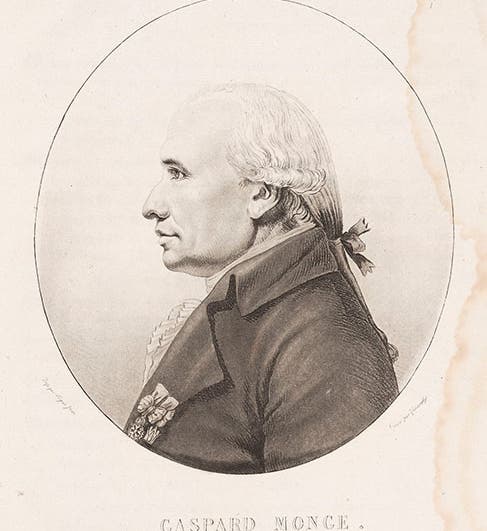

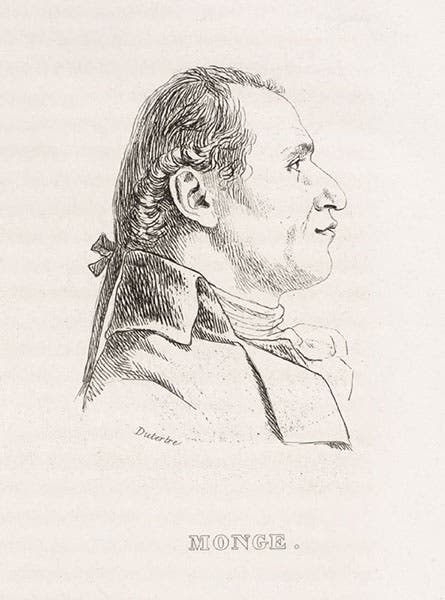

Monge was one of the few scientists to have a full-page portrait included in the Description de l'Égypte (first image), but since we have few other visual aids for Monge, we also show the portrait sketch by André Dutertre (third image), who did portraits of almost all the savants, many of which we have reproduced in this series.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.