Scientist of the Day - Friedrich Koenig

Johann Friedrich Gottlob Koenig, a German inventor, was born Apr. 17, 1774. Koenig came out of his apprenticeship as a printer/compositor with a deep desire to improve the printing press, a device that had hardly changed since Gutenberg's day. He wanted to make many of the operations, such as feeding, inking and printing, mechanical, and he wanted to speed up the whole process. He began making improved presses around 1803, and he soon realized that his presses could easily be powered by steam, so that they were fully mechanical. He could find no financial support in Germany, so he moved to England in 1807 and soon found a financial backer. Koenig was full of ideas but he was not a mechanic, so he invited Andreas Bauer, a German friend and an expert craftsman, to come to England to build the actual presses. By 1810 they had patents, by 1811, a working machine, and by 1812, an improved one. The Koenig-Bauer press had twin steam-driven rotary cylinders that were self-inked, and could print two sheets simultaneously, about 800 of them per hour. Their press caught the eye of the owner of The Times of London, who secretly ordered two presses, stipulating a press speed of 1100 sheets per hour per press. The presses were constructed and delivered, and in the early morning of Nov. 29, 1814, the complete run of The Times was printed on the two Koenig-Bauer steam-powered presses. The publisher, who had kept everything under wraps to avoid a mutiny from his pressmen, revealed the truth in that Nov. 29 issue, claiming that this was the greatest innovation in printing since the invention of the printing press. If he was wrong, it was not by much.

Koenig and Bauer fell out with their London backer, who did not want to make machines to sell, and so the two moved back to Würzburg, a sleepy rural Bavarian town, in 1817, and set up their own company, using an old monastery as a factory. They were a good team, the company prospered, and soon Koenig and Bauer presses were in great demand all across Europe, especially for newspapers. In fact, the company still exists, as Koenig Bauer AG (usually referred to as KBA), and they still make presses, specializing in those that print bank notes. They take great pride in their founders, and there are statues of both Koenig and Bauer on the grounds of the plant in Würzburg; here is Koenig's. The dual portrait of Koenig and Bauer that we open with (first image) also seems to emanate from a KBA collection, although documentation is lacking.

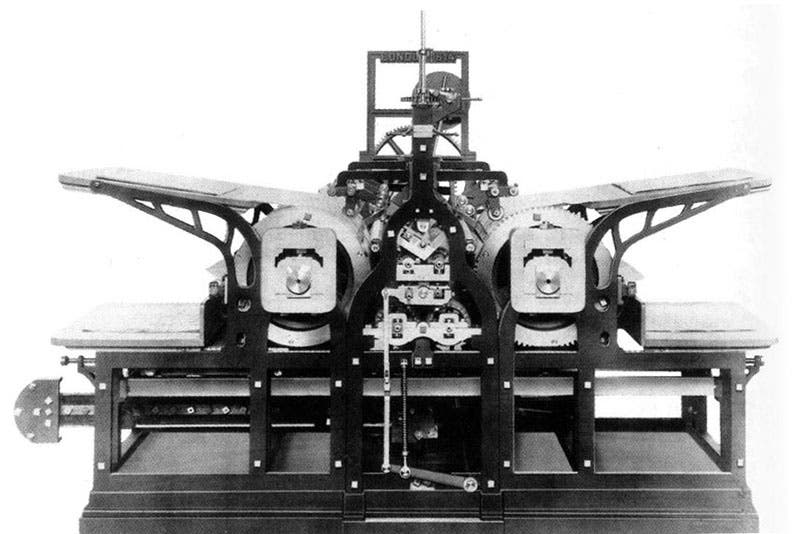

There is a photograph of the 1814 Koenig-Bauer Times press on the website of The Times (second image), and also on Wikipedia, but information as to the present-day whereabouts of the press is not provided, nor is the authenticity of the photo verified in any way. The photograph is not that old, so if the caption is true, one of the Times presses survived into the 20th century. I hope it is in a printing museum somewhere. KBA maintains such a museum in Würzburg, and you can find an informative 7-minute video on YouTube that looks at Koenig and Bauer’s achievement and shows some of the original Koenig-Bauer presses, but it is not claimed that any of them is one of the two presses that ushered in the great printing revolution of 1814.

Should you be a philatelist with a special interest in the history of science and technology, Germany issued a postage stamp in honor of Koenig and his steam-powered press in 1968. Why 1968? I have no idea.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.