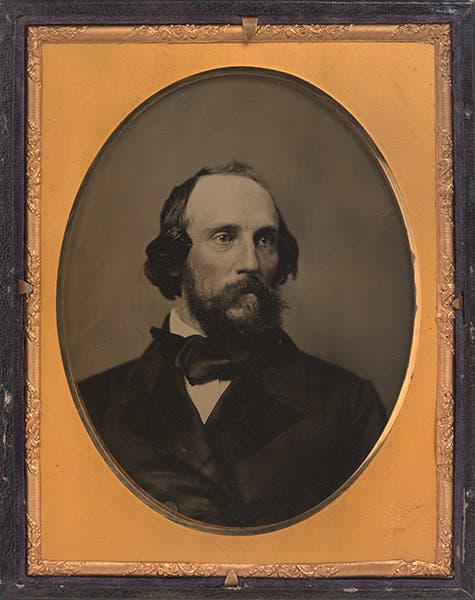

Scientist of the Day - Frederick Lander

Frederick West Lander, a U.S. Army officer and engineer, died Mar. 2, 1862. Lander took an active role in one of the Pacific Railroad Surveys in 1854, the one that surveyed a route across the northern plains to Puget Sound (this survey was led by Isaac Stevens, about whom we have not yet written, but we have published a post on the artist who accompanied Stevens and Lander in 1854, John Mix Stanley). After the Pacific Railroad Reports were published, starting in 1855, planning for a transcontinental railroad came to a standstill, since the southern, central, and northern blocs refused to compromise on a route. Instead, notice was taken of the tens of thousands of emigrants who were slowly wending their way by wagon across a vast country totally devoid of roads. In 1857, Congress passed the Pacific Wagon Act, and the first project launched under the Act was the construction of an improvement to the Oregon Trail – a cut-off, if you will – in the Green River basin in Wyoming. The current (1857) trail took a dip to the south toward Fort Bridger, and the country that the Trail passed through in this region was desert-like, without grass and water for the livestock.

Lander was put in charge of a project to survey and construct a new section of road for the Oregon Trail (actually, he was second-in-command for a year, until the chief engineer, a drunken political appointee, abandoned the enterprise under threat of mutiny, and Lander was bumped up into the vacancy). Lander was amazingly good at the job. He and his crew carved out 250 miles of road – the first road in the West that was actually constructed. They levelled forests and moved millions of cubic feet of earth. They uncovered springs and used them to fill reservoirs, found locations for fords, and when necessary, built bridges. The road was completed in 1859 and was called, right from the outset, Lander's Road, or the Lander Cutoff. Lander even wrote and published a Lander Trail Guide to aid travelers in navigating his highway.

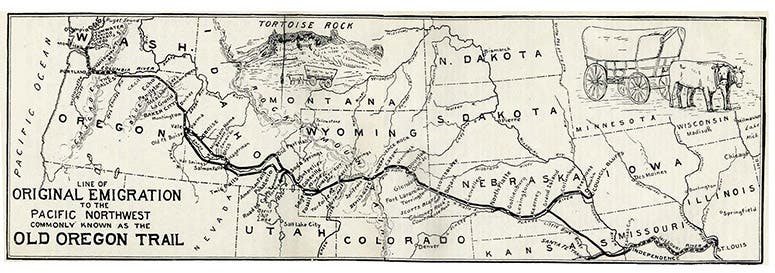

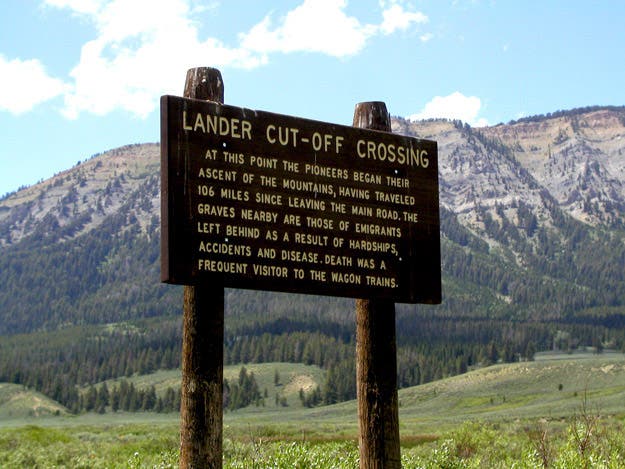

In the map included here (third image), which is a modern map of the original Oregon Trail, Lander’s Road would go from Devil’s Gate in western Wyoming, just where the Trail starts to dip south, and across to old Fort Hall, in eastern Idaho. Not only was the Lander Road a better avenue for cattle, because of the abundant supply of grass and water, but it shortened the route to Oregon by some 80 miles or 7 days. It is estimated that 13,000 settlers used the Lander Cutoff in the first year of operation, 1859, and traffic continued apace until 1869, when the completion of the transcontinental railroad made wagon travel much less attractive. Many wooden markers along the present-day location of Lander’s Road commemorate various landmarks associated with the Cutoff (fourth image).

In 1859, Lander received orders to survey the nearby Wind River Range, and for this occasion he took along several young artists, including Albert Bierstadt. When the Civil War intervened and the survey was cut short, Lander was reassigned to the Union Army, and the artists returned east and began turning out large oil paintings of the sublime West, paintings that now hang in museums all over the country. We include here a painting of the Wind River Range made by Bierstadt in 1861 (fifth image).

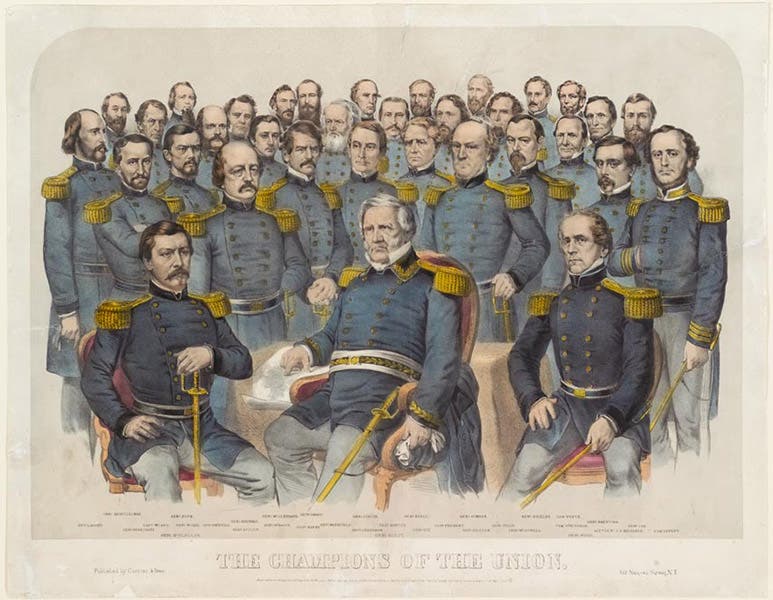

Lander, like hundreds of his military engineer contemporaries who were promoted into combat, did not long survive the War; no sooner was he promoted to General than he was wounded at Edward’s Ferry in the fall of 1861, and he died of complications on Mar. 3, 1862. He was 40 years old. Before his death, Nathaniel Currier included Lander in a lithograph commemorating the leaders of the Army of the North; he is the leftmost figure, in the third row (sixth image).

Bierstadt commemorated the man who introduced him to the West with a fabulous painting, The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak, which he finished in 1863, showing a summit in Wyoming that Bierstadt himself named after the recently deceased General (first image). This artwork is 10 feet by 6 feet and currently hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City; it is one of the most lustrous examples of what we now call the Rocky Mountain School of painting. We featured this and several other Bierstadt paintings in our post on Bierstadt.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.