Scientist of the Day - Frederick Banting

Frederick Banting, a Canadian physiologist, was born Nov. 14, 1891. In the fall of 1920, Banting, who was then at the University of Western Ontario, groping about for a research project, read a journal article that suggested that perhaps the islets of Langerhans, clusters of cells in the pancreas, might help regulate blood sugar levels. Unregulated blood sugar is one of the signs of diabetes mellitus, a scourge of a disease that, in its type-1 form, strikes young children and causes them to waste away and die. In 1920, there was no cure for diabetes. Banting later said that, the very night after reading the article, he dreamed of finding such a cure.

Banting submitted a research proposal to John McLeod, chair of the physiology department at the University of Toronto, and McLeod, against his better judgment (Banting had no track record whatsoever, and McLeod didn't think his proposed experiments would really work), provided Banting with a lab, an assistant, and funding. This was in May of 1921. That summer, Banting and Charles Best, his graduate assistant, learned how to prepare pancreatic extracts, and they experimented on dogs, showing that when the pancreatic duct was tied off in a lab animal, the pancreas withered but the islets remained unaffected, and no diabetes developed. When the pancreas was removed, there was an onset of diabetes, but the blood sugar levels would return to normal when some of their pancreatic extract was injected. They had trouble getting an extract that worked until McLeod provided them with the help of a biochemist, James Collip. The extract contained what is now called insulin.

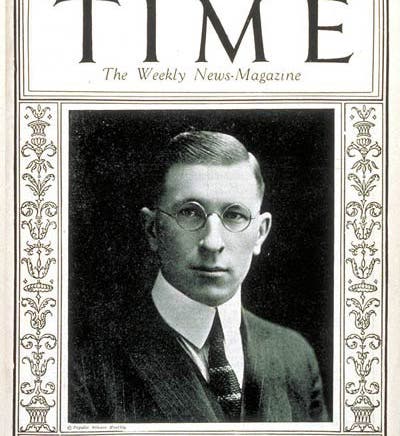

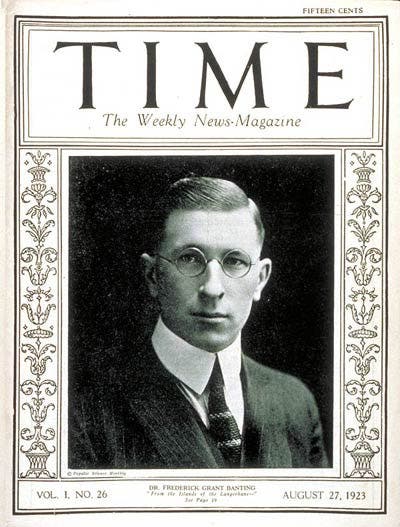

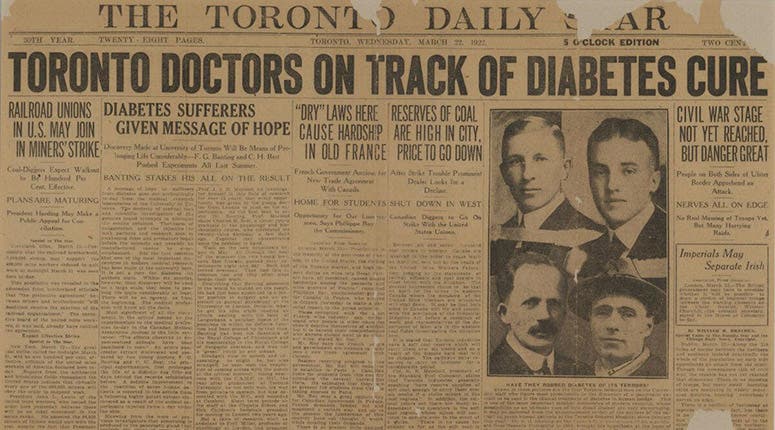

Banting gave a paper on the success of his experiments in December of 1921, but it wasn't until March of 1922 that his work came to public attention, when he cured a dying young lad, 14-year-old Leonard Thomas, of diabetes, by regular injections of insulin. That was news, and soon Banting was a public hero and on the front page of newspapers everywhere (third image). The very next year, 1923, Banting was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine/Physiology, which promoted him to the cover of Time magazine (first image). However, it was a shared prize, and the other recipient was his boss, McLeod. By all reports, Banting was not at all happy about this, and thought Best should have been the co-recipient, and he made a show of awarding Best half of his Nobel earnings. Not to be outdone, McLeod awarded half of his monetary award to the biochemist, Collip. Everyone was happy, and no one was happy. So it goes.

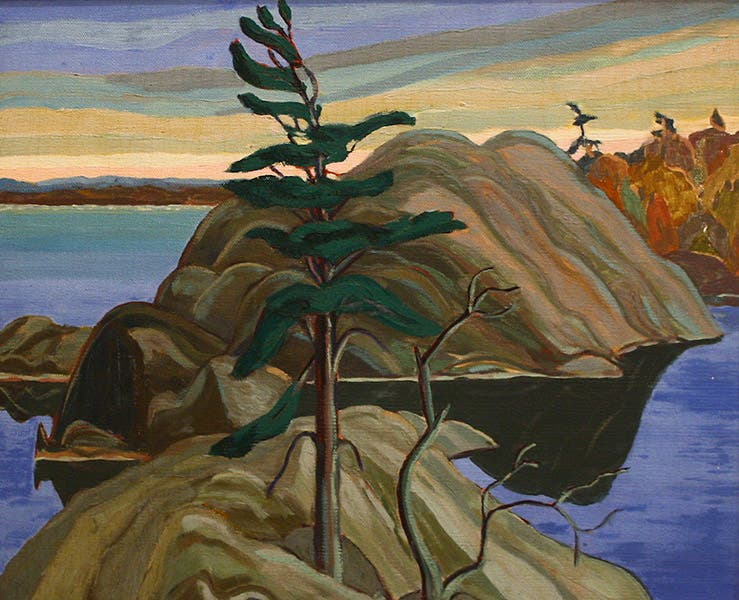

Banting, as one might gather, was a fairly colorful character, and he was well-liked by most of his colleagues, except the one who shared his Nobel Prize. He took up painting, learning his craft from one of the Group of Seven, an art school that was Canada's answer to the Rocky Mountain School of American Art (fourth image). He gave all of his paintings away, but after his death, a “Banting” became a highly collectable work of art. If you search for “Banting painting” on Google Images, you will discover that his paintings command a hefty price at auction. In 2012, three small panel paintings by Banting were discovered in a safe deposit box belonging to the Banting Foundation. No one knew how they got there, but the foundation directors were more than pleased at the windfall (fifth image).

Banting's death was as unusual as his life. During World War II, he was an officer in the Canadian medical corps, and on a flight from or to Gander, Newfoundland, his plane crashed into a lakeside, and all aboard were killed.

The house in London, Ontario, where Banting read his article and dreamed his dream on Oct. 30/31, 1920, is now a National Historic Site of Canada and a museum, known as Banting House. There is a statue of Banting outside, journal in hand, and research project about to come to mind (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.