Scientist of the Day - Frederic Ward Putnam

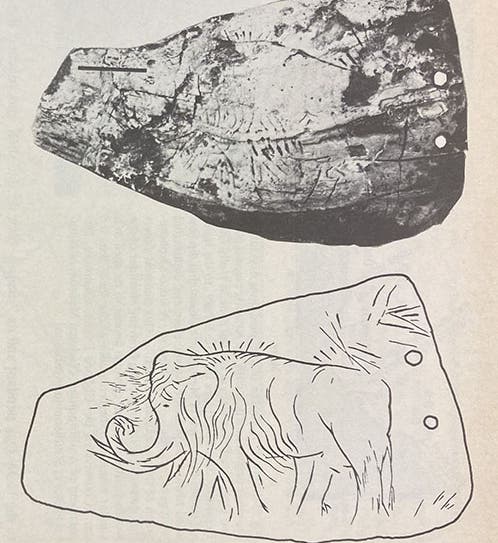

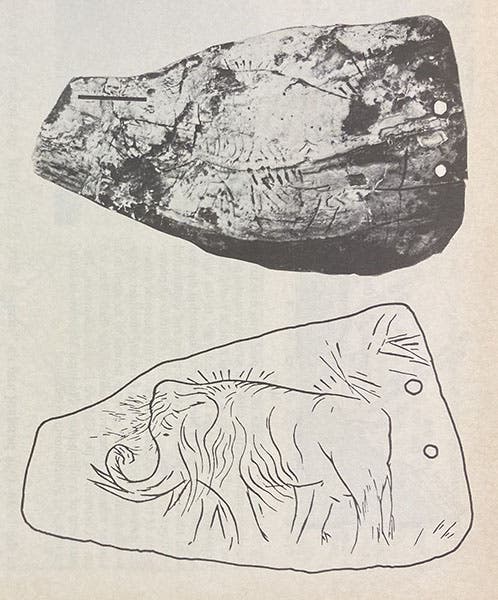

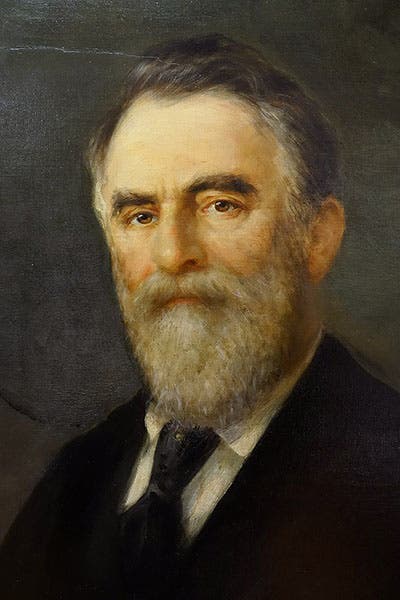

Frederic Ward Putnam, an American anthropologist, was born Apr. 16, 1839. Putnam had been curator of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard since 1875. In 1889, his assistant, Hilborne Cresson, brought him a shell gorget or pendant, that he claimed to have found at Holly Oak, Delaware, some 25 years earlier (first image). The pendant was engraved with an image of a wooly mammoth, and would seem to have been good evidence that ancient Americans were making Paleolithic art at the same time as their counterparts in Europe. Since this was one of the few pieces of evidence that there was an American Paleolithic, this should have been a sensational discovery, and should have made Cresson’s career, and perhaps Putnam’s. Yet Putnam put the pendant in a drawer and never mentioned it again. Cresson, five years later, committed suicide by putting a gun to his head in a New York City park. He must have suspected that Putnam knew that the Holly Oak pendant was a fake, and that Cresson had fabricated it and tried to pass it off as genuine.

Why was Putnam suspicious? Because the mammoth on the Holly Oak pendant is a dead ringer for the famous Mammoth of La Madeleine, which had been found in 1864 by Edouard Lartet and which depicts a wooly mammoth, engraved on a piece of mammoth tusk (third mage). Probably working from a print, Cresson had simply copied the La Madeleine mammoth onto an old shell pendant that he had found. The original mammoth engraving from La Madeleine was missing its feet, because there was no room for them on the tusk. The Holly Oak mammoth is also missing its feet, yet there is plenty of room for them there. This, and the close resemblance of Cresson’s pendant to the La Madeleine engraving, was probably what set off the alarm bells for Putnam. Rather than call out Cresson, he did something more devastating – he ignored it. Cresson finally caved in under the weight of the unstated accusation and took his own life.

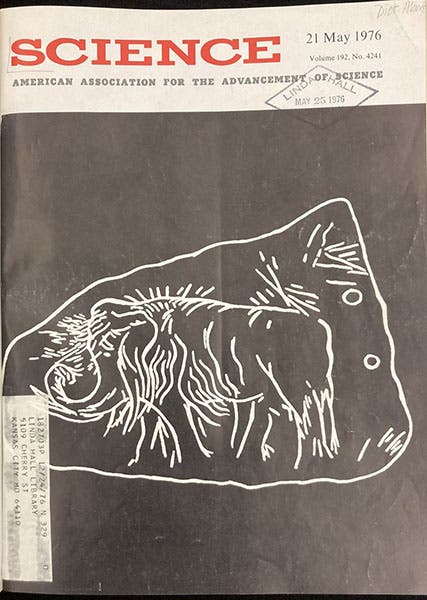

The pendant was rediscovered around 1976, still in the drawer where Putnam had put it, and the new finders, not knowing the back-story, published the pendant as genuine – a white-on-black drawing even appeared on the cover of Science in 1976. But the pendant was subsequently radiocarbon dated and found to be only about 1200 years old, some 15,000 years younger than the La Madeleine mammoth.

Putnam, Cresson, and the fraudulent nature of the Holly Oak pendant were the subject of a lengthy sidebar (4 pages, 75-78) in First Peoples in a New World: Colonizing Ice-Age America, by David J. Meltzer (Univ. of California Press, 2009). Meltzer was one of those who, after the 1976 article in Science, arranged for radiocarbon dating of the pendant, showing that the whelk lived about 875 C.E. and was about as far removed from the American paleolithic as an object could get.

We displayed the original mammoth of La Madeleine in our exhibition, Blade and Bone: The Discovery of Human Antiquity (2012); see our catalog entry on Edouard Lartet.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.