Scientist of the Day - Frederic Ives

Frederic Eugene Ives, an American inventor, died May 27, 1937, at age 81. Ives was raised in Connecticut, and when his father died while he was still young, he was apprenticed to a local printer in Litchfield, where he quickly distinguished himself as an inventive and hard-working printing genius. He never had any formal education, which is quite amazing, given some of his later inventions. He moved to Ithaca, New York, and managed to talk his way into a position at Cornell as head of their photographic lab, and this was well before he was 20 years old. It was while at Cornell that he seems to have had his first great inspiration, coming up with a new way to print photographs. A photograph is a continuously toned medium, but most printing processes cannot handle continuous tone. A wood engraving, for example, prints either black or white, and the tone comes from alternating the white and black spaces, and the same is true for engraving and lithography. There were a few continuous-tone printing processes, such as the Woodburytype, which were extraordinarily good, but they were expensive and time-consuming, and hardly suitable for media such as newspapers or magazines. Ives invented the half-tone photo-engraving process. In half-tone printing, the tone is provided by tiny black dots. If the dots are large and there is little or no white space between them, that area of the image will be dark gray or black. If the black dots are tiny, surrounded by ample white space, then that region will be light gray or white. Middle-sized dots produce middle-range tones. You are all familiar with half-tone photographs, since practically any printed illustration you are likely to see will be a half-tone. Ives is generally credited with the invention of half-tone printing, but there were a number of people who had been playing with the process for 20 years before Ives turned his attention to it. What Ives did, that none of his predecessors could manage, was develop a commercially successful process to easily turn a photograph into a half-tone print, which he did by 1881. Printers soon discovered that you could use very fine screens to convert a projected image into a dot matrix, and Ives by 1884 had developed the most successful of these screens, called the crossline screen. Within just a few years, half-tone illustration would become the standard in books, magazines, and newspapers. Ives profited from this not at all, because he did not patent his invention. Our opening image is a detail of a halftone print of 1892, enlarged to show the halftone grain. You can see the full image here, where the grain is no longer visible. Whistler’s real title for his mother’s portrait, Arrangement in Gray and Black, becomes even more appropriate for the reproduction, Ives went on to invent other optical devices and new photographic techniques, most of which he did patent. I thought we might mention one other: his contribution to color photography. Ives invented a process that he called Kromography, whereby he photographed three separate images of a scene using red, green, and blue filters, producing three sets of negatives. Because he was interested in stereo photography, these filtered negatives were in pairs. If one inserted them in a special viewer, which he called a Kromskop, filters in the box would transform the three sets of negatives into a fully colored stereo image. We link to a montage of three black-and-white negatives of a vase of flowers, a pair of stereo colored images, and an enlargement in full-color as it might be viewed in the Kromscop. Ives had this process all worked out by 1897, the date of these negatives. The Kromagram process was viable only for about 10 years, until others figured out how to do this without special equipment, which made color photography much cheaper. But before Kromography became obsolete, Ives travelled to San Francisco, in April of 1906, just after the famous earthquake, and took several sets of stereo images of the devastation. These images were lost for 100 years and turned up only a few years ago in a Smithsonian Institution file. Here is one stereo pair. Those are pretty amazing color views after 114 years, and you have to remind yourself that these are not color images, but reconstructed color from black-and-white negatives.

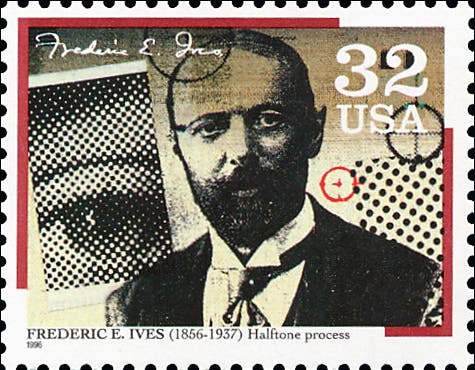

In 1996, the U.S. Postal Service issued a set of four commemorative stamps that they called "Pioneers of Communication". The four men chosen to be honored were all late 19th-century inventors, and Ives was one of them. His 32¢ stamp is our second image. It shows not only his portrait, but a good specimen of half-tone printing. A block of all four stamps shows us the other honorees: They are: Eadweard Muybridge, who used a series of cameras to make moving images (top left at the link); Ottmar Mergenthaler, who invented the Linotype (top right at the link); and William Dickson, who with Edison created the first motion picture camera and projector (bottom right at the link). We have written Scientist of the Day blogs on Muybridge and Mergenthaler, but we have never tackled Dickson. We shall see what happens on his upcoming birthday on Aug. 3. A photograph of Ives, taken in 1905, shows him at age 49, with 32 years left to live. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.