Scientist of the Day - Franz Kruckenberg

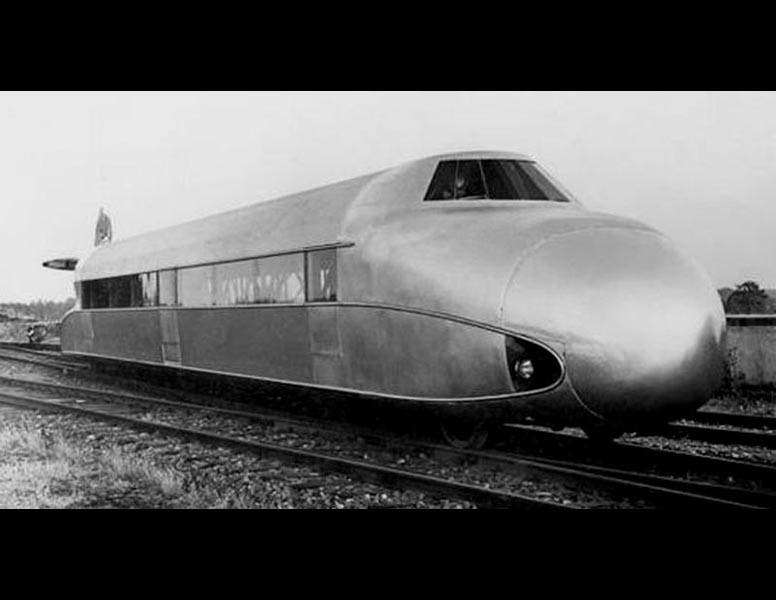

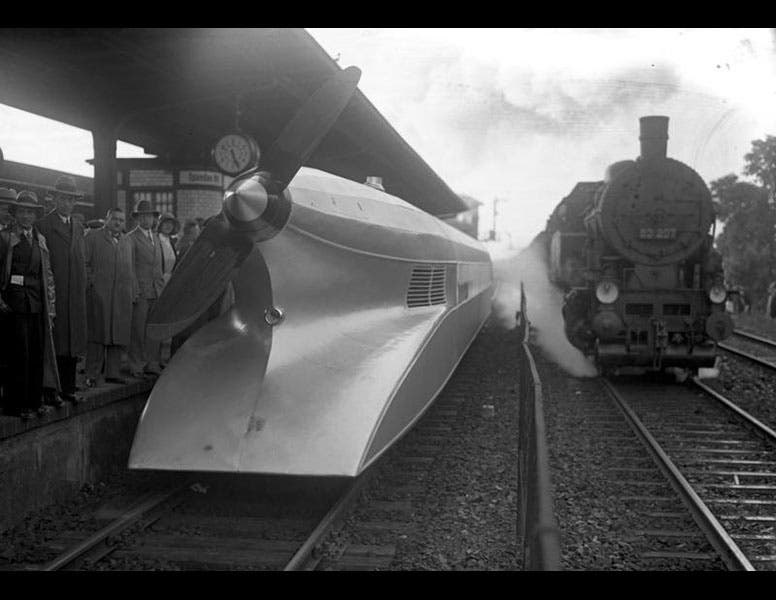

Franz Kruckenberg, a German mechanical and aeronautical engineer, was born Aug. 21, 1882. After gaining experience in aircraft design during World War I, Kruckenberg spent most of his life designing high-speed railways, but he is best remembered for a single creation: the Schienenzeppelin, or Rail Zeppelin, that he unveiled in 1930 (first and second images). The Rail Zeppelin was not a locomotive but a powered railcar, which means that a single unit contained both the motive power and accommodations for passengers, rather like a streetcar. The novelty lay in the propulsion system; the Schienenzeppelin, just like the Zeppelins of the air, was powered by a propeller. The propeller was in the rear, for obvious reasons, and was driven by a BMW aircraft engine mounted in the back (third image). The car was very long (nearly 90 feet) and very light, built of aluminum, and handsomely streamlined, so that it looked quite fast, even standing still.

The Rail Zeppelin, however, like anything built for speed, looks better in motion. Here is a short video of the railcar in action (commentary is in German). If you would like to see the Rail Zeppelin without its skin, so you can appreciate the aluminum design, here is a longer 5- minute video, showing quite a number of test runs (you don’t need to watch all of them). Note that the propeller shaft is inclined down a few degrees, to help keep the railcar on the track. In these clips, Kruckenberg is the fellow with the Van Dyke beard – you will see him both as co-engineer and as good-looking-fellow-standing-around-looking-smart.

On June 21, 1931, the Rail Zeppelin set off down the tracks from Hamburg to Berlin and reached the speed of 230 km/hour, or about 140 mph. That was fast, for 1931. It is fast for 2018. That was the speediest any railcar would travel for twenty years, and it still is the highest speed ever reached by a gasoline-powered railcar. So what happened to the Rail Zeppelin? Only one was ever built, and it performed admirably for 8 years, but then, in 1939, it was decommissioned and dismantled. We don't really know why it was not more successful. Modern commentators often guess that it must have been dangerous in stations, with that whirling propeller, and perhaps noisy and turbulent as well, but that was not a problem in the initial years, and so far as we know, no one was ever sliced up by a Rail Zeppelin blade or blown off a station platform. We do know that the aerodynamic shape was quickly applied to conventional diesel powered locomotives, so that they got faster and more efficient, and perhaps engineers just preferred working with tried-and-true railway technology and leaving the propellers to the aeronauts.

But the Rail Zeppelin is legendary among railroad buffs, and popular even with model railroaders. As early as 1932, the venerable German toy company, Märklin, issued a model Schienenzeppelin (fourth image), and they have been producing them ever since, in every scale imaginable (fifth image). You can even find a few videos of these models in action, which are kind of fun; here is a link to one. But as best I can tell, the models are driven by motorized wheels, not by the whirring propeller, which seems a little like cheating.

It is really too bad that no real Rail Zeppelin survives - it would be quite a collector’s item for the Jay Leno’s of the railroad world. About all we have to remember Kruckenberg by, aside from the Märklin toys, is a plaque on his place of birth in Uetersen, northwest of Hamburg (sixth image). Like everything else about this piece, the text on the plaque is in German. But the picture on the plaque of the Schienenzeppelin needs no translator.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.