Scientist of the Day - Franz Andreas Bauer

Linda Hall Library

Franz Andreas Bauer (also known as Francis Bauer) was born on 4 October 1758 in Feldsberg, Moravia, now the Czech Republic, into a profoundly artistic family. Franz was the middle of three brothers, all of whom built remarkably productive careers celebrating the inherent beauty of nature. The oldest brother, Josef Anton Bauer (1756-1830), succeeded their father as court painter to the Prince of Liechtenstein in Vienna, later becoming the keeper of Vienna’s prestigious royal gallery. The youngest brother, Ferdinand Bauer (1760-1826), studied natural history illustration alongside Franz, leaving Vienna in his twenties to travel the world as an illustrator. As young men, though, Franz and Ferdinand stayed close to home, receiving artistic training first from their mother, and then from physician and naturalist Father Norbert Boccius, each producing thousands of sketches and watercolors prized for their detail and delicacy. Both brothers focused their sights on botanical illustration, securing steady patronage from Nikolaus von Jacquin, Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Schönbrunn Palace. In the early-1780s, though, the Brothers Bauer parted ways, each embarking on their own international careers.

Ferdinand left Vienna first, sailing on a series of expeditions across the globe as a traveling natural history illustrator. Through the first decades of the nineteenth century, Ferdinand worked alongside naturalists like John Sibthorp and Robert Brown on trips through the Mediterranean and across the Pacific Ocean, culminating in several massive—and massively expensive—illustrated volumes. Although his work was highly revered and his reputation sound, the artist racked up significant debt, eventually forcing him to move back to Vienna. He retired to a small residence near, once again, the Schönbrunn Botanical Garden, spending his days hiking and sketching the local landscape until his death in 1826.

Franz Bauer, though perhaps less adventurous in his travels, fared slightly better than his brother after leaving Vienna. In the late-1780s, Franz moved to England with Baron Joseph Franz von Jacquin, his former patron’s son. Settling in London, the illustrator impressed the influential Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society and adviser on an ongoing plan to restructure the rapidly growing Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (second image). Apparently pleased with Bauer’s skill and dedication, Banks appointed Franz the first permanent, in-house botanical illustrator at the royal gardens, tasked with studying and sketching the thousands of new plants sent back to London by collectors working around the world. Unlike his brother, Franz stayed put, settling into his house on the Kew grounds for the next fifty years. Securing a comfortable yearly salary of £300, Franz spent the rest of his life working with both domestic and exotic plants while instructing both royals and burgeoning naturalists (including the first Director of Kew, William Jackson Hooker) in the art of botanical illustration (third image).

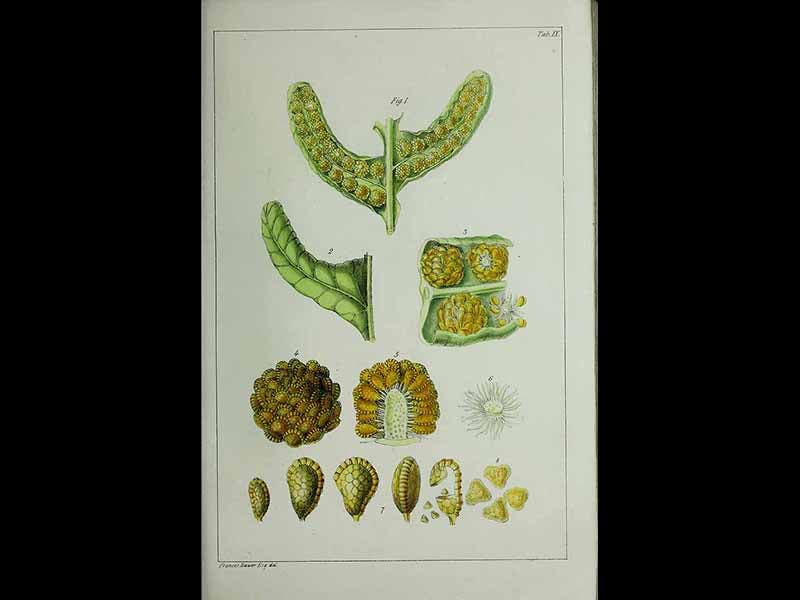

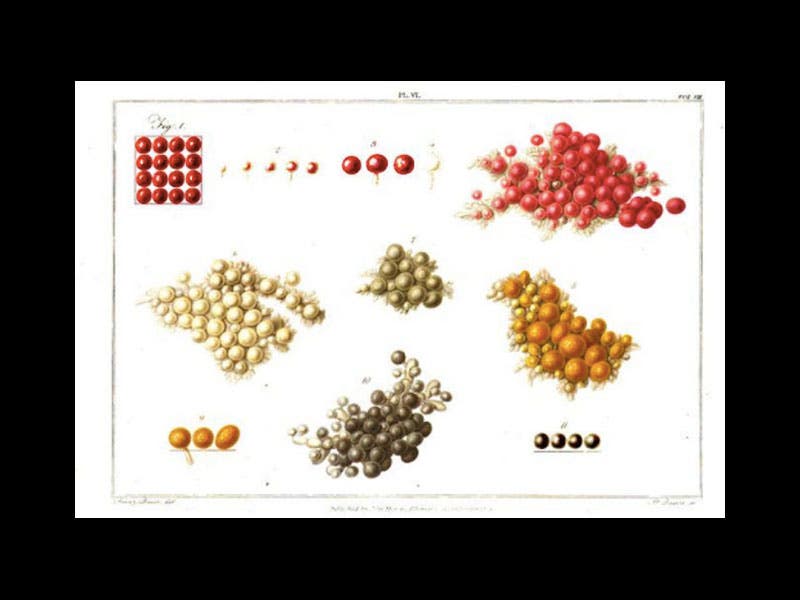

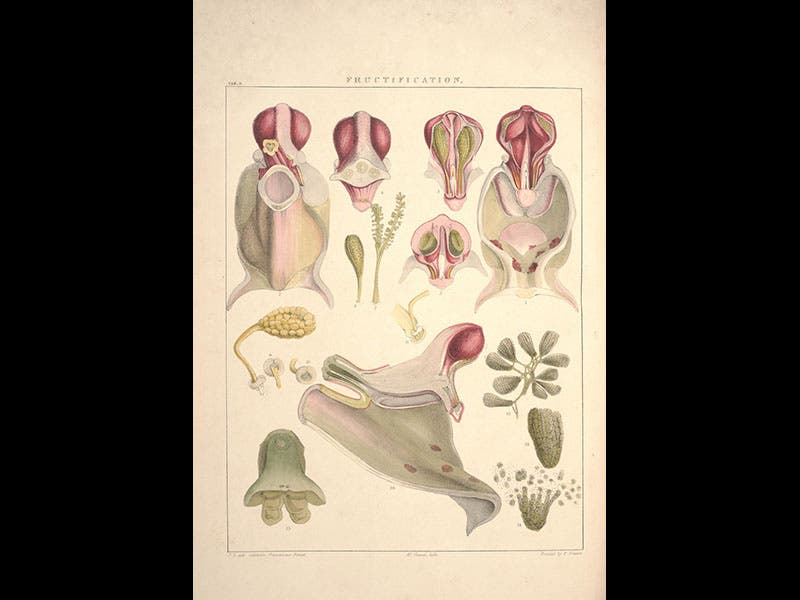

In an era rife with natural history illustrators, Franz Bauer distinguished himself by studying microscopy, using his skills of observation to dissect and accurately draw specimens’ reproductive organs, a set of techniques especially useful in classifying plants according to the Linnaean System. When not illustrating countless plants sent back to Kew both for publication and private study, Franz worked alongside distinguished naturalists to create etchings and lithographic images for various periodicals from the Transactions of the Linnean Society to the Transactions of the Horticultural Society, oftentimes stepping outside the traditional boundaries of illustration to put forth scientific observations of his own. While working on microscopic images of pollen for Joseph Banks and flies for Everard Home, Franz even conducted his own experiments on the algae responsible for “red snow,” publishing several articles from 1819-1820 (fourth image). Ultimately, though, the middle Bauer brother was known for his stunningly beautiful illustrations of orchid anatomy and the remarkable South African Strelizia depicta (fifth and sixth images). Most of Franz’s illustrations are held in archives in Britain and Germany, unbound and unpublished.

Although historians have noted the oftentimes confusing similarity in style between Franz and Ferdinand Bauer, Ferdinand is known for his complex use of color while Franz, besides including microscopic views of plants, usually gravitated towards pure color washes. Franz Bauer died on 11 December 1840, and was buried, fittingly, in the churchyard at Kew, his legacy commemorated by a small monument. Keen readers will notice, when paging through early-nineteenth century periodicals, the faint “del. Fr. Bauer” gracing the edge of particularly beautiful plates, marking Franz Bauer’s lasting impact on the history of art and science.

Elaine Ayers is a doctoral candidate in the Program in the History of Science at Princeton University, and is the 2017-18 80/20 Fellow at the Linda Hall Library. She works on the history of natural history, collecting, and museums in the nineteenth century. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to eayers@princeton.edu.