Scientist of the Day - François-Sulpice Beudant

François-Sulpice Beudant, a French geologist and mineralogist, was born Sep. 5, 1787, in Paris. He attended the École Polytechnique and the School of Mines, then taught math at Avignon and physics at Marseilles, before settling on mineralogy, which would keep his attention for the rest of his life. He had studied briefly with René Just Haüy, the “father of crystallography,” which probably had some influence on his career choice. Beudant would write a treatise on mineralogy, then revise it, and in the second edition (1830-32) identify hundreds of minerals which still carry the names he assigned. He would succeed Haüy as professor of geology and mineralogy at the University of Paris.

However, we do not have any of Beudant's treatises on mineralogy, which is a shame, but there it is. However, we do have a work of Beudant's that is seldom discussed, but which has to be his most sumptuous and beautiful publication. It was the result of a trip he made to the mines of the Kingdom of Hungary, upon request of the King. Out of that year-long tour, somehow, came a three-volume quarto text set, accompanied by an atlas of hand-colored plates, called: Voyage minéralogique et géologique, en Hongrie: pendant l'année 1818, published in 1822. All of our images today, except for the two portraits, were taken from this work.

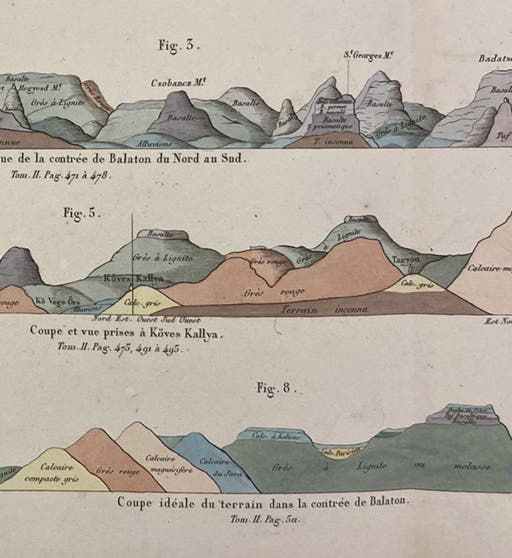

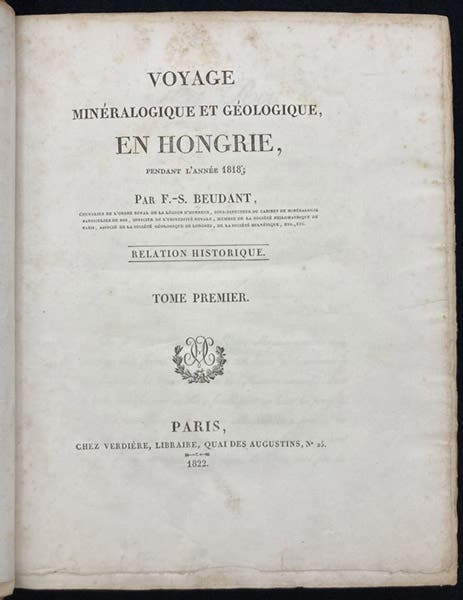

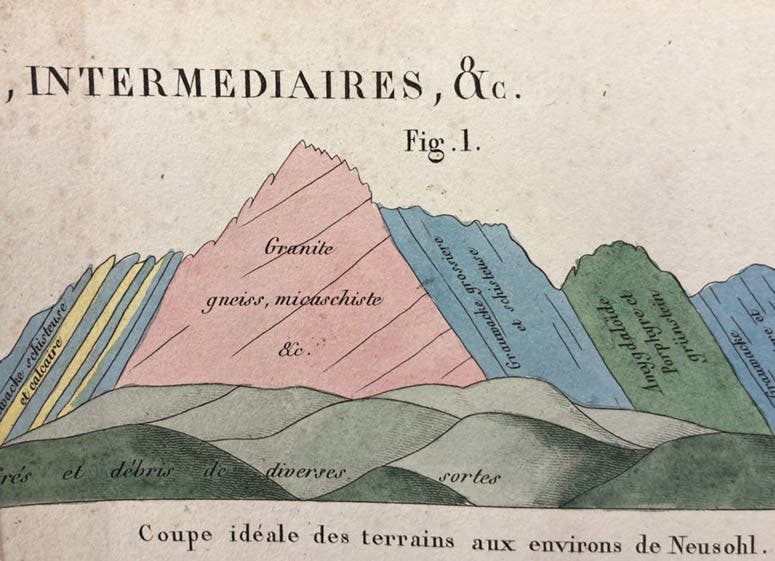

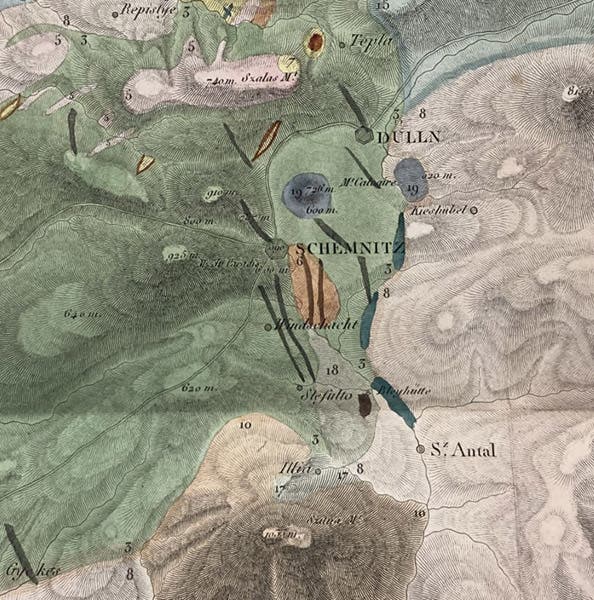

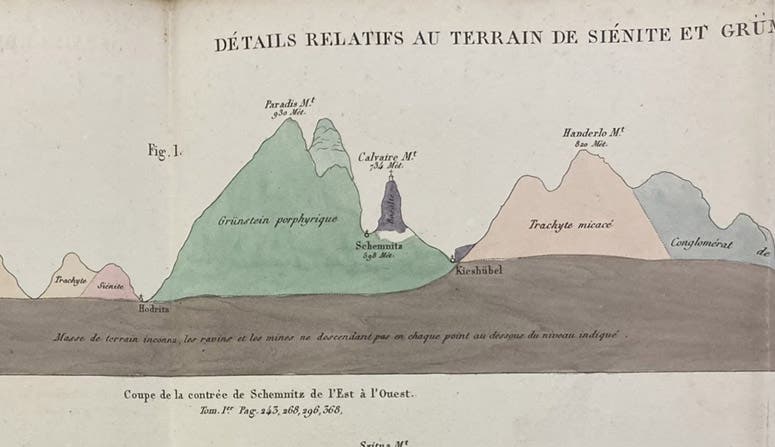

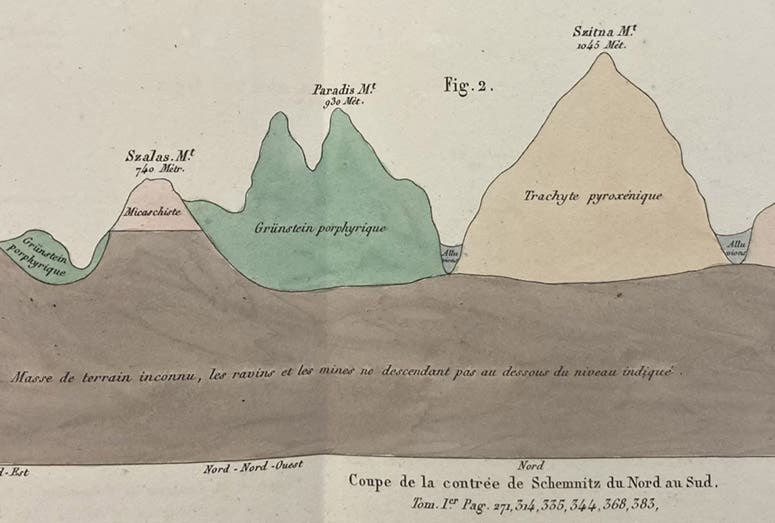

I did not linger long with the text, although someone certainly should. Instead, I looked at the 7 plates and the 3 maps in the atlas. They make up a full volume, because each engraving is folded again and again to fit into even the confines of a large quarto. The 7 plates are each a collection of geological sections, where a section is just a slice down through the earth, usually vertically, conveying information that must usually be inferred, unless Nature has kindly provided her own real slice of terrain. If photographed in their entirety, all details on these plates would be unreadable, so I here show details of some of the sections and one of a map.

Some of the sections are ideal ones, meaning that the information depicted was extracted from hundreds of observations and then presented in a "clean" form that you would never see in Nature (fourth image). Others show real cuts at specific places that are named, although even here, they have been cleaned up, to give us an artist's version of the countryside. One of the geological maps shows the region around Schemnitz, which we now call Banská Štiavnica, a mining town in what is now Slovakia. There was a Mining Academy in Schemnitz, the first founded in Hungary, where Beudant apparently spent some time, for good reason, for it sits in a large caldera where there used to be a huge volcano, now collapsed, surrounded by more recent peaks comprised of various igneous rocks. We show a detail of a section running east and west (fifth image), where you can see Schemnitz nestled in next to a gray peak called Mount Calvary, and then a section running north and south (sixth image). In the detail of the geological map, centered on Schemnitz, you can find the mountains (like Mount Calvary and Mount Szitna) that you see in the sections (seventh image).

A geological section, east to west, through Schemnitz (now Banská Štiavnica), Kingdom of Hungary (now Slovakia), and the surrounding caldera and mountains, detail of a large hand-colored engraving, Voyage minéralogique et géologique, en Hongrie: pendant l'année 1818, by François Beudant, vol. 4, 1822 (Linda Hall Library)

A geological section, north to south, through Schemnitz (now Banská Štiavnica), Kingdom of Hungary (now Slovakia), and the surrounding caldera and mountains, detail of a large hand-colored engraving, Voyage minéralogique et géologique, en Hongrie: pendant l'année 1818, by François Beudant, vol. 4, 1822 (Linda Hall Library)

Finally, I call your attention back to our first image, which shows three sections of regions north of Lake Balaton in Hungary. Are these not beautiful? I have looked at hundreds of geological sections over the years, and I do not think I have ever seen any more handsome than those of Beudant, in their clarity, labeling, and coloring. I do not know to what extent Beudant was involved in the engravings, since the artist for the plates is not identified, but they were certainly based on information and sketches that Beudant provided. So we give him the credit here.

Our copy of this work has not been scanned, because no one has ever asked for it, and indeed I did not even know about it until I looked up our Beudant holdings and pulled it off the shelf. It would also be quite a project to scan the large plates in the atlas, printed on thick paper that resists being unfolded and flattened (I took these images with an iPhone and had a hard time doing so). But I think we will attempt to scan it soon, to get some scholar interested in taking a closer look at this geological treasure.

I was not happy with the portrait of Beudant that I had to use, since it is clearly a copy of a copy of an unidentified engraved original, which I could not run down (second image). I almost prefer the campy portrait that is part of an enameled memorial plaque that someone erected in Balatonfüred, Hungary, very near the area where the sections shown in our first image were drawn (eighth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.