Scientist of the Day - François-Jules Pictet

François-Jules Pictet, a Swiss zoologist and paleontologist, was born Sep. 27, 1809, making him 7 months younger than Charles Darwin. He studied in Paris (taking classes from Georges Cuvier, the founder of vertebrate paleontology), and in Geneva; in 1834, he assumed the chair of zoology at the Academy of Geneva, when Augustin-Pyramus de Candole retired. Pictet also devoted time to the Natural History Museum of Geneva, to which he gave many specimens, and where he established the library.

Pictet wrote quite a few books, but we have only a second edition of his Traité élémentaire de paléontologie, originally published in four parts plus atlas in 1844-46, and republished in 1853-57, which is the edition we have. Fortunately, it is a splendid set, and we will focus on it for this post.

Pictet’s Traité was really a first of its kind, a fossil encyclopedia. The four volumes of text (which I didn’t spend much time with) were accompanied by an atlas of 110 plates, which I know quite well, as I have used it for many years. It has thousands of figures of nearly every kind of fossil that had been found to date, vertebrate and invertebrate. We will focus on vertebrate fossils here, since most readers can relate more easily to giant sloths than to barnacles.

Vertebrate paleontology was only about 40 years old in 1844. Georges Cuvier began his career around 1804, writing about the American mastodon found by the Peale family in the United States, and the Megatherium, or giant sloth, brought back to Spain from Argentina (see our post on Juan Bautista Bru de Ramon). In his Recherches sur les ossemens fossils (Researches on fossil bones, 1812), Cuvier argued that these were animals of a bygone age and were now extinct. Extinction was a new idea that Cuvier made plausible. In later editions of 1821-24 and 1834-36, Cuvier added to the list, including the newly discovered giant reptiles found in England, the Megalosaurus and the Iguanodon, soon to be named dinosaurs, as well as plesiosaurs and the like.

But Cuvier’s Recherches was not a fossil encyclopedia, but rather a series on monographs, with no attempt to be comprehensive. There was an encyclopedia with fossils in it, the 1824 six-volume Supplement to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, where you could find nice engravings of the mastodon and the megatherium. But again, it was hardly an encyclopedic presentation, in spite of the fact that it was called an encyclopedia.

So Pictet was onto something new. Every fossil vertebrate that had been found anywhere had an entry, and a picture. Actually, there were two kinds of figures. Pictet would show the actual bones that had been found of the animal under discussion. And then, if there was one available, he would show a skeletal reconstruction. Cuvier had done this too, but not in a way that was useful to the general reader.

Pictet’s plates, even though they have scores of figures on each one, are clean and easy to grasp, unlike Cuvier’s. Detailed captions, printed at the front of the Atlas, identify each figure and its source. It is as easy to use as any modern reference source – easier, really. I reproduce here one plate full size (fourth image), labelled “Megalonyx. Scelidotherium. Glyptodon,” and show a detail of the Glyptodon for our first image. We wrote about Joseph Leidy and his monograph on the Megalonyx several weeks ago.

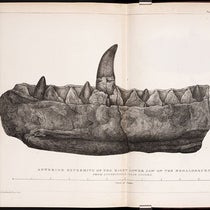

Our other images are all details from plates. Our fifth image shows the bones of the dinosaur Megalosaurus, described by William Buckland in 1824, and using his figures (the jaw bone at the top, and the leg bones at left). The word “dinosaur” had been invented by Richard Owen in 1842, just in time for Pictet to use it, which he did.

Another plate with fossils of cats and canids includes the skull of a Smilodon, or saber-toothed cat, which we think of as an American predator, because of the abundance of its remains in the La Brea tar pits. But Pictet’s specimen came from the Auvergne region of France, and he called it Machairodus (sixth image).

We once wrote a post on Richard Owen in which we discussed briefly his monograph on the Mylodon (1842), which included a large foldout skeletal restoration of the giant sloth, with a tiny modern sloth skeleton for comparison (first image in our post on Owen). Pictet read that same book and extracted a simplified version of Owen’s complex lithograph for the plate on giant sloths, from which we pulled a detail (seventh image).

We have not written a post on Louis Agassiz’s Recherches sur les poissons fossils, 1833, a beautiful work with hand-colored lithographs of fossil fish, an oversight we will correct at the next opportunity. But Pictet knew it well, and has several figures that depict slabs of limestone embedded with fish fossils that he took from Agassiz. We show one of those (eighth image).

Finally, we show part of a plate that includes a Plesiosaurus skeleton more or less as it was found, by Mary Anning. I believe Pictet’s figure was taken from the engraving in William Buckland’s Bridgewater treatise of 1836, but I am not really sure. Whatever the source, it adds a nice sinuous note to a plate that would otherwise be overly regular (ninth image).

I decided to include the title page (third image), even though images were at a premium today, because the full title is instructive: Traité de paléontologie: ou Histoire naturelle des animaux fossiles considérés dans leurs rapports zoologiques et géologiques – Treatise on paleontology: or Natural history of fossil animals considered in their zoological and geological relationships. Pictet understood, as not everyone did in 1844, that fossils were important not only for zoology, but also for geology, since they are always found in a geological matrix and thus have something to tell us about the history of the Earth, as well as the history of life.

Most of the photographs of Pictet that survive show him as a man in his sixties, much older than the 35-year-old who wrote the Traité or the 44-year-old who revised it (second image). But he looks mellow and congenial, a man worth knowing. He died on Mar. 15, 1872 (10 years before Darwin), and was buried in the Cimetière des Rois in Geneva, where his grave marker may still be seen.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.