Scientist of the Day - François Huber

François Huber, a Swiss naturalist, died Dec. 22, 1831, at the age of 81. He is one of the heroes in the history of the study of bees, which is the more remarkable, as Huber was completely blind, having lost his sight at the age of 15.

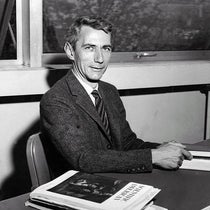

Huber's father was a well-known painter, student of music and literature, and gifted conversationalist (according to Voltaire), and the family was well enough off that they could afford to hire companions for young François when he went blind. One of those was a young peasant, another François, last name Burnens, who was happy to read to Huber, and who seemed to take as much pleasure in learning as Huber did. Together they discovered the writings on insects of René-Antoine Reaumur, and Huber decided that, with the aid of Burnens, he would investigate the lives of bees. Much about bees was still unknown or misunderstood. Aristotle had written about bees, but he thought the "singular bee" – the large bee essential to the survival of any hive – was a male, a king, and it was not until the work of Jan Swammerdam in the late 17th century, aided by a microscope, that it was learned that the king is actually a queen, since she has ovaries, which Swammerdam magnified, observed, and engraved, and that the drones are males. But neither Swammerdam nor anyone else had observed a queen mating. That became Huber's vicarious quest.

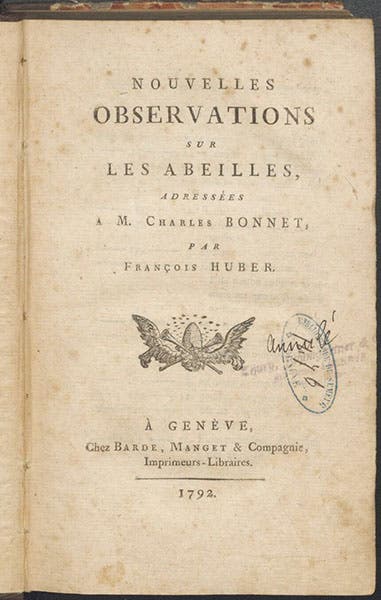

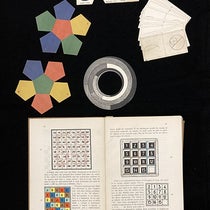

To answer the questions about bee copulation, Huber, first of all, invented a new kind of hive, the book or folio hive, which consisted of individual frames, or books, hinged so that one could "leaf through" the hive and see what every single bee was doing, a precursor to the Langstroth hive of the 1850s (third image). The book hives were presumably built by Burnens, or under his supervision. The two men discovered that the queen did not mate in the hive, and that if she were confined there and not allowed to leave, she remained infertile. So mating must occur outside the hive.

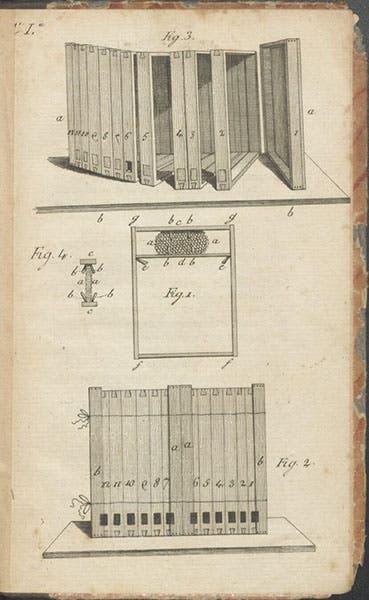

In the summer of 1788, Huber and Burnens did an experiment, in which a young infertile queen was allowed to leave the hive. She flew up in the air over the field and Burnens tried to follow her flight with his eyes, although he was not successful in observing a mating. When the queen returned after a short flight, they examined her, and she was physically unchanged. So they turned her loose, and again she flew aloft, and this time, when she returned, she was swollen with a milky fluid in her abdomen, and soon began laying hundreds of fertile eggs. Although they had not observed an actual mating, they presumed that this took place with drones in the air, and they even found, in the spermatic mass, what were eventually identified as body parts of drones, since the physical act of mating is fatal for the drone.

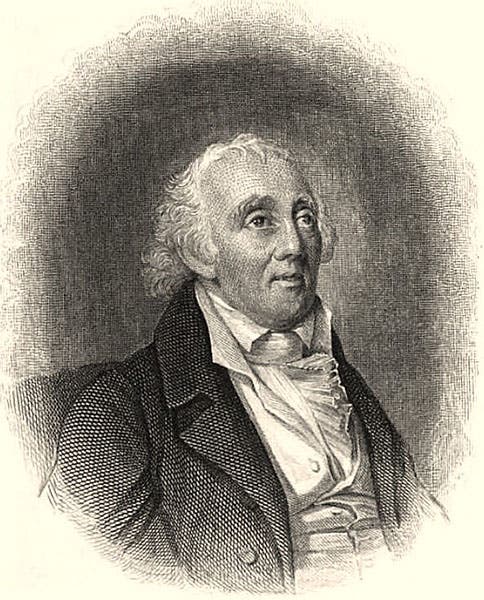

So the secret was a secret no more – the queen bee mates on the fly, on what will later be called her “nuptial flight,” and once fertilized, can produce eggs by the thousands for life. Huber announced their discoveries in a series of letters written to Charles Bonnet, the eminent French natural philosopher, which were published as a book, Nouvelles observations sur les abeilles (New Observations on Bees) in 1792. We have a copy of this work in our history of science collections (second image), and it is available online. It is illustrated with two plates at the end, one showing the book hive (third image), and the other revealing the reproductive anatomy of a drone bee (fourth image). It is not clear who drew these, but it certainly was not Huber. Whether Burnens had artistic talent, I do not know.

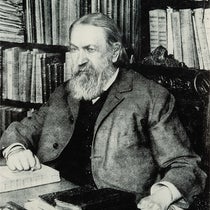

Later naturalists were at first unsure about “nouvelles observations sur les abeilles”, written by someone who was unable to observe bees at all, and had to use an uneducated peasant as his eyes. But as more and more of their discoveries were confirmed, Huber received more and more acclaim, and he continued to observe and write additional books, although we do not have any of these in our Library. When William Jardine wrote his volume on bees for his Entomology series for the Naturalist’s Library in 1840, he began with an extended homage to Huber, and even included a portrait, which is the source for our portrait here (first image), courtesy of Wikipedia, since we don’t have Jardine’s Entomology either (note to Santa).

There is a brief but lovely account of Huber and his work in The Dancing Bees: Karl von Frisch and the Discovery of the Honeybee Language, by Tania Munz (University of Chicago Press, 2016). When this book was published, Dr. Munz was vice president for research and scholarship at this very library. We still miss her.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.