Scientist of the Day - Francis Ronalds

Francis Ronalds, an English inventor and electrical engineer, was born Feb. 21, 1788. Ronalds came from a family of cheese purveyors, a profession he adopted for some years (while considering changing his name to Wensleydale). But around 1810, he abruptly shifted his attention to electricity (this was 10 years after Volta's battery had opened up a new world for electrical investigators). Ronalds invented a slew of ingenious electrical devices, including an electrograph that would measure the electricity in the atmosphere. He also started collecting books and pamphlets on electricity, a collection that would grow into a sizable library.

In 1816, Ronalds built a working telegraph in the garden of the family house in Hammersmith in west London. Part of it was underground, but above ground he strung out 8 miles of insulated wire in ribbon-candy fashion, with clocks at each end whose faces contained letters instead of numbers; the electrical signals in some way synchronized the clocks and spelled out a message. Apparently, the device worked; he gave a demonstration for the Admiralty in 1816, offering it to them gratis, but the Secretary of the Admiralty, John Barrow, rejected it as an unnecessary invention, preferring the semaphore telegraph then in use. Two years later, Barrow distinguished himself by sending out the first ships in search of a Northwest Passage, but he has never quite lived down the ignominy of rejecting the electrical telegraph as useless. It would be 20 more years before England re-entered the telegraph business, and by that time, they were well behind the Americans. Many today regard Ronalds as the true inventor of the telegraph, and there was considerable scholarly commotion in his behalf in 2016, the bicentennial of his invention.

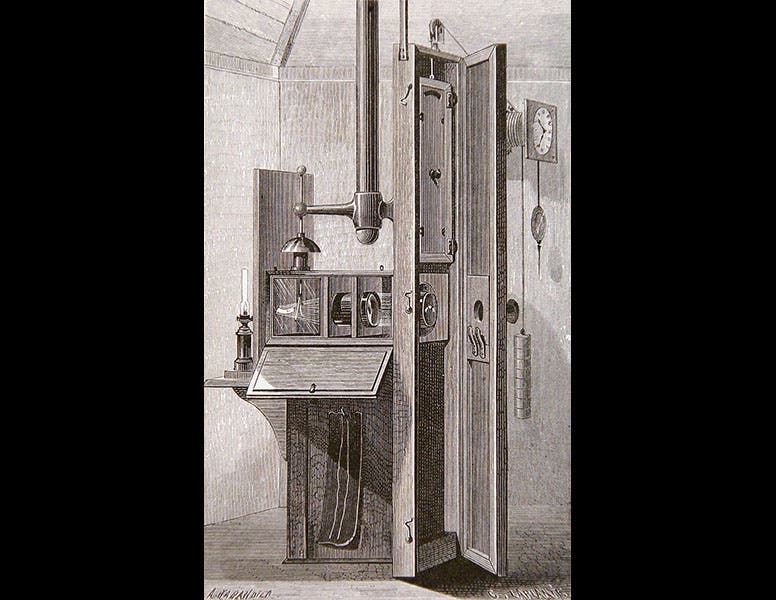

Ronalds continued to invent and collect books throughout a very long life (he died in 1873, at age 85). In the 1840s, with the invention of photography, he found a way to continuously photograph a full 24 hours of readings of his electrograph (second image). His Library grew to accommodate 2000 books and 4000 pamphlets; after his death, it was deposited with the Institution of Engineering and Technology in London, and finally donated to that institution in 1976.

Ronalds published a book on his telegraph, Descriptions of an Electrical Telegraph, and of some other Electrical Apparatus (1823). This work is surprisingly not in our collections, a deficiency we will try to remedy in the near future. Ironically, we just last week acquired the principal book on semaphore telegraphy, the system that Barrow preferred to Ronalds’ electrical telegraph.

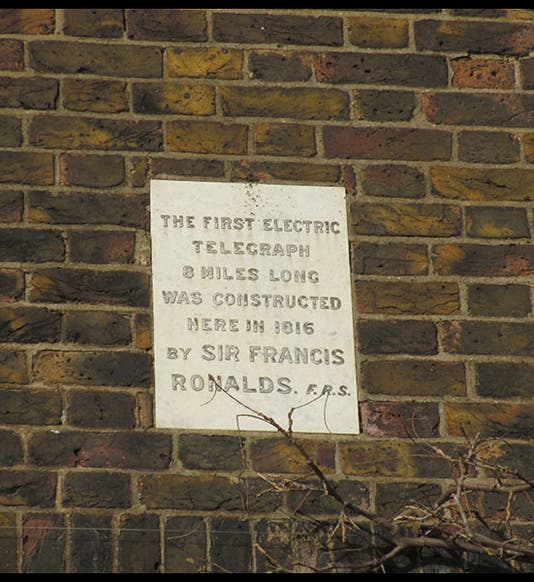

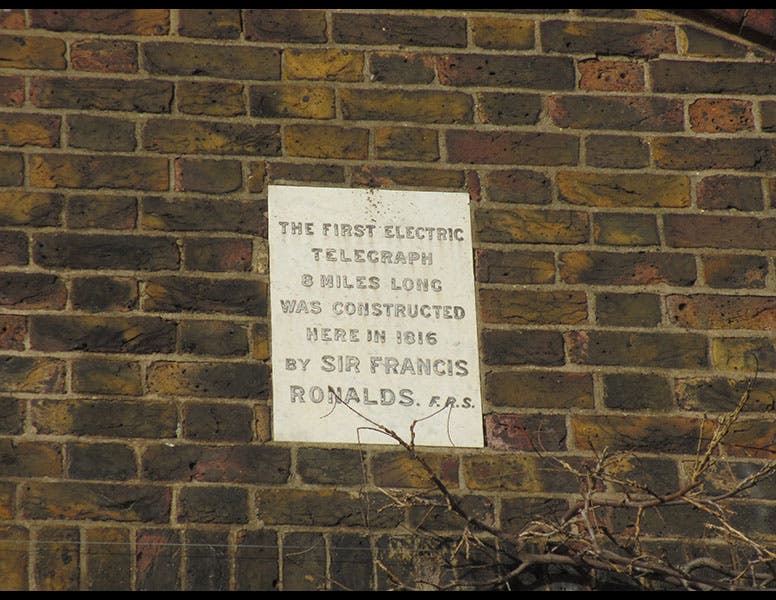

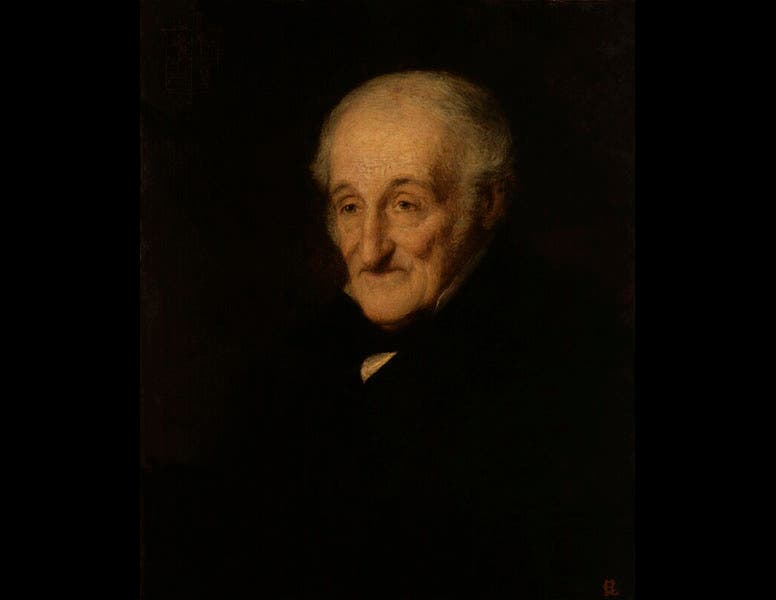

As a final note, the Ronalds house in Hammersmith, where his telegraph was first laid out, was acquired in the 1870s by designer William Morris, and is today known as Kelmscott House. There is a plaque on the wall that commemorates Ronalds' garden telegraph (first image). The only surviving portrait of Ronalds, painted not long before his death, is in the National Portrait Gallery, London (third image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.