Scientist of the Day - Francis Hauksbee

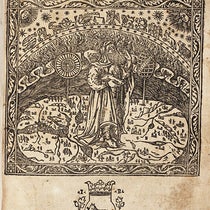

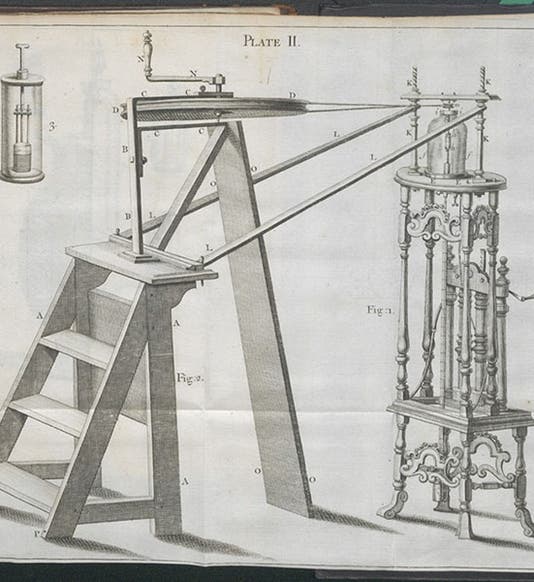

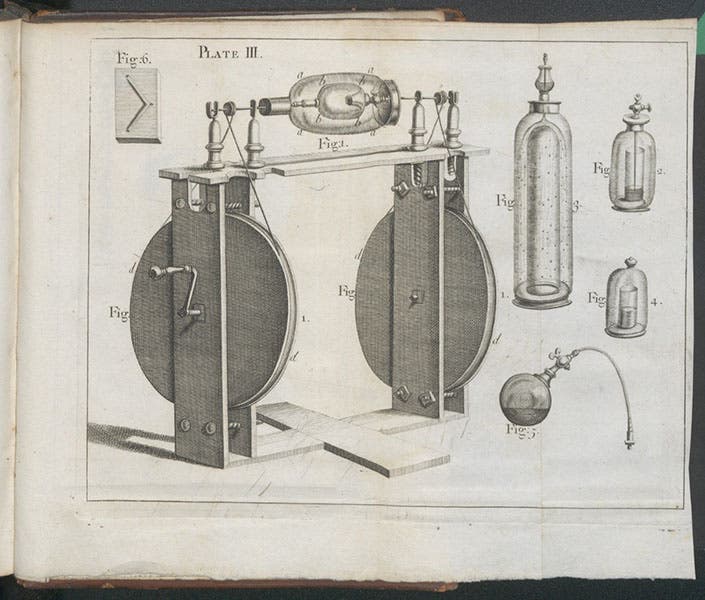

Francis Hauksbee, an instrument maker and experimental demonstrator, died on an unknown day in April 1713; he was born sometime in the early 1660s. Hauksbee is a textbook example (literally) of how experimental inquiry coupled with shrewd insight can lead to the discovery of new and unexpected phenomena. Hauksbee was employed by the Royal Society to conduct regular experiments for the Society’s weekly meetings, a practice introduced by Robert Hooke in 1663 and revived in 1703 by the new president, Isaac Newton. Hauksbee's first experiments concerned what was called "barometric light," a phenomenon investigated long before by Robert Boyle but not at all understood. If you shake a barometer (a sealed tube containing mercury with a vacuum at the top), the mercury running down the sides of the tube produces a glowing light. Hauksbee wondered if the mercury was essential to the light, or whether any kind of rubbing of the tube would do, and he built an ingenious piece of apparatus with which he could rub an object in a partial or complete vacuum. In the engraving (first image), we see his air pump, an evacuated glass vessel, and a mechanism that can rotate an object inside the vessel. He discovered that all you need in order to produce light by attrition (rubbing) is to rub something in a partial vacuum – the mercury is irrelevant. Incidentally, the air pump he invented for the occasion – with two barrels to pump on both the up and down strokes – became the prototype for all English air pumps for the next 40 years. He gave us a better look in a separate engraving (second image, just below).

One of the objects he rubbed in his vacuum chamber was amber, a well-known source of electrical effects, and so Hauksbee became interested in electricity. He discovered that if you rubbed a glass tube with a cloth, the glass becomes electrically charged and will attract bits of chaff. He wondered if evacuated glass tubes would produce the barometric light, and found that indeed they would. But strangely, the tubes lost their electric charge when evacuated.

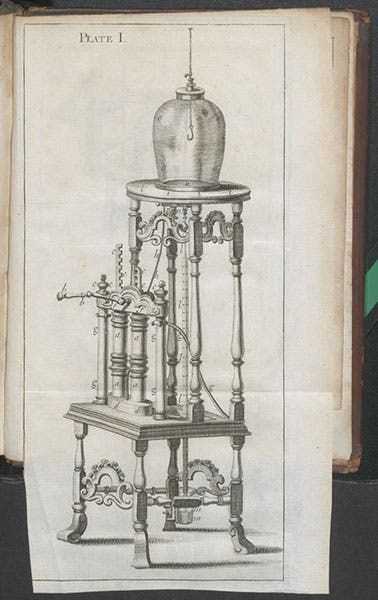

Finally, Hauksbee made another piece of apparatus to generate light. Instead of rotating and rubbing things inside an evacuated vessel, why not just rotate the evacuated vessel and rub it with your hands on the outside? That was a brilliant intellectual (and experimental) insight. The apparatus worked as imagined and he could produce a bright glow by rubbing the rotating globe with his hands. And now came the crucial leap! If a glass tube produces light when evacuated and electricity when the vacuum is removed, what happens if one lets the air back into the rotating globe? He did so, and – snap,crackle, and pop! – he had the world’s first static electricity generator (third image, just above). He could produce all sorts of sparks from his triboelectric generator, as he called it, simply by rubbing the rotating globe with his hands. It was truly a revolutionary device, and when rediscovered in the 1740s by other investigators, it made possible the discovery of a wealth of new electrical phenomena, including the devastating Leyden jar.

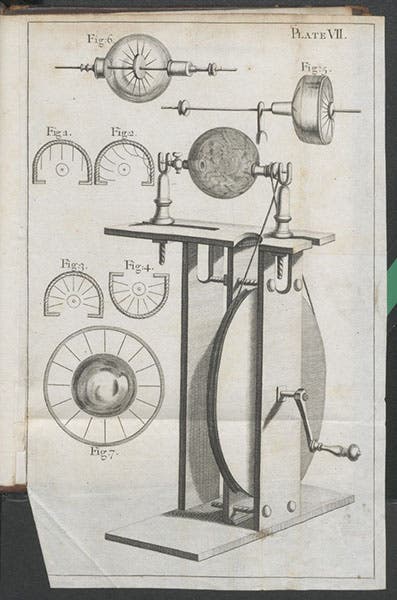

Hauksbee published the results of his work on barometric light and electricity in Physico-mechanical Experiments on Various Subjects: Containing an account of several surprizing phenomena touching light and electricity, producible on the attrition of bodies : with many other remarkable appearances, not before observ'd (1709). There are seven engraved plates in the book, the source of all our images. We show one more plate that has another rotating rubbing device, as well as some evacuated glass vessels which he ingeniously designed so he could drip mercury onto glass and produce barometric light without a barometer (fifth image, below). Hausbee’s book was reprinted in 1719, which is the version most commonly held; we have both editions in our collections.

As is the case with most artisans, we have no portrait of Hauksbee to help us remember him, nor (to my knowledge) does any of his original apparatus survive. However, the Royal Society museum and archives is surprisingly rich in treasures, and I hope someone will write to say that a double-barreled air pump or triboelectric generator has indeed made it down through the centuries and may still be viewed. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)