Scientist of the Day - Francesco Maurolico

Francesco Maurolico, a Sicilian mathematician and classical scholar, died on July 21 or 22, 1575, having been born in Messina on Sep 16, 1494. His parents were Greek, so he grew up with a mastery of the Greek language, and his father made sure he was well-trained in mathematics. As a result, Maurolico developed a keen interest in the surviving works of the great Greek mathematicians, such as Euclid, Archimedes, and Apollonius. He found that many of their works had been shabbily treated by medieval and Arabic translators, and that the surviving texts, both Greek and Latin, were riddled with errors. He resolved to take on the task of producing and publishing new editions and translations of all of them, which would have been quite an undertaking.

Maurolico compiled editions of Apollonius and Archimedes, but they were not published in his lifetime. The Conic Sections of Apollonius had to wait until 1654 to see the light of print (we do not have this), and the opera of Archimedes was not published until 1685, more than a century after Maurolico’s death (this one we do have).

Maurolico also wrote one highly original treatise on optics, Photismi de lumine et umbra, which he finished in 1521; it would have been of great assistance to Johannes Kepler in his optical researches, but the Photismi was not published until 1611. As we do not own the 1611 edition, we will defer discussion until such time as we do have it in our collections. It is the work for which Maurolico is best known, because of its originality.

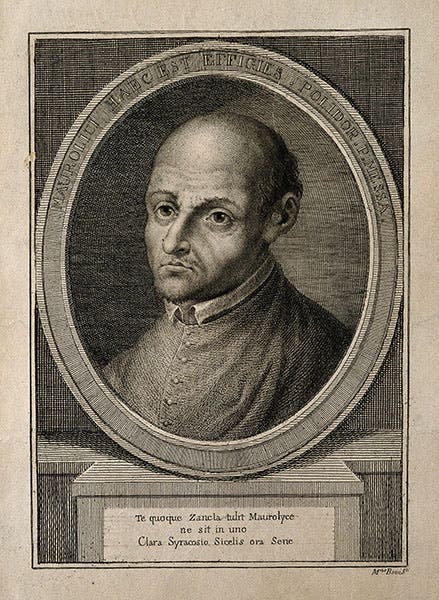

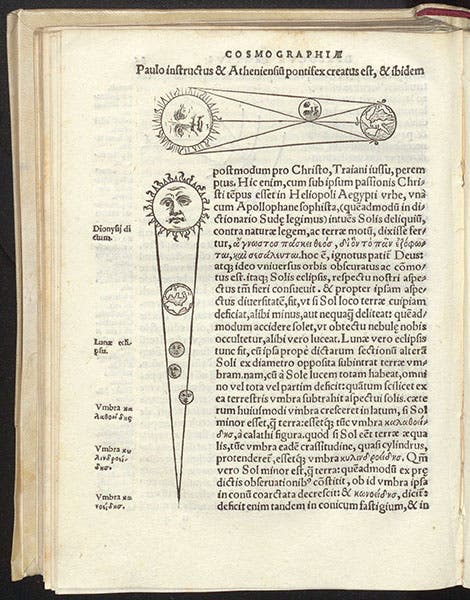

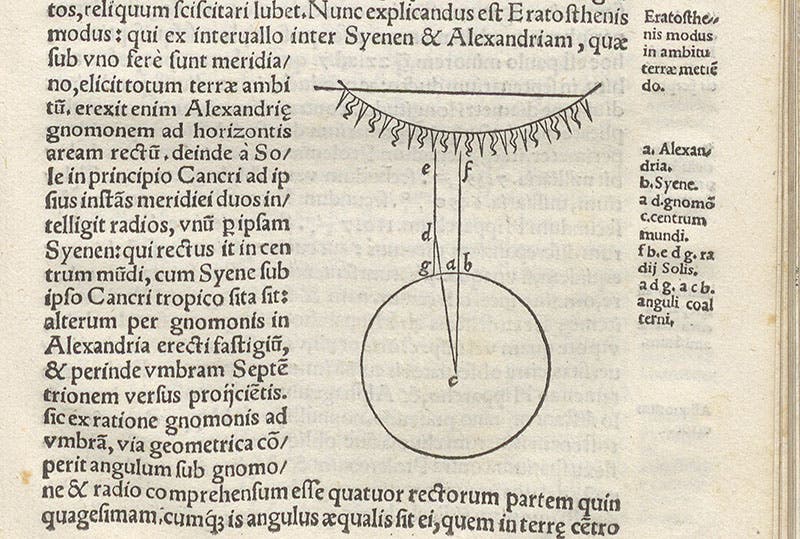

The one Maurolico work, published in his lifetime, that we do have, is his Cosmographia, which appeared in 1543 (third image). Cosmography as a science was a Renaissance invention, a curious amalgam of geography, astronomy, travel narrative, and world almanac. There were many different kinds of cosmography. One of the most popular of the genre, the Cosmographia (1544) of Sebastian Münster, was filled with historical tales and woodcuts of foreign lands and faraway monsters, and had little mathematical component (although Münster wa an extremely competent mathematician). Maurolico's cosmography was different - there was much more discussion of basic astronomy, inspired by the Sphere of Johannes de Sacrobosco and by the works of Johannes Regiomontanus and Georg Peurbach (fourth image). And there were lots of mathematical asides, such as Maurolico's discussion of the method by which Eratosthenes had determined the circumference of the Earth in the 3rd century B.C.E. (fifth image).

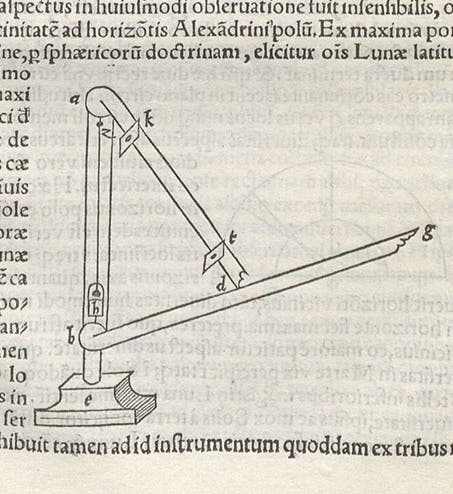

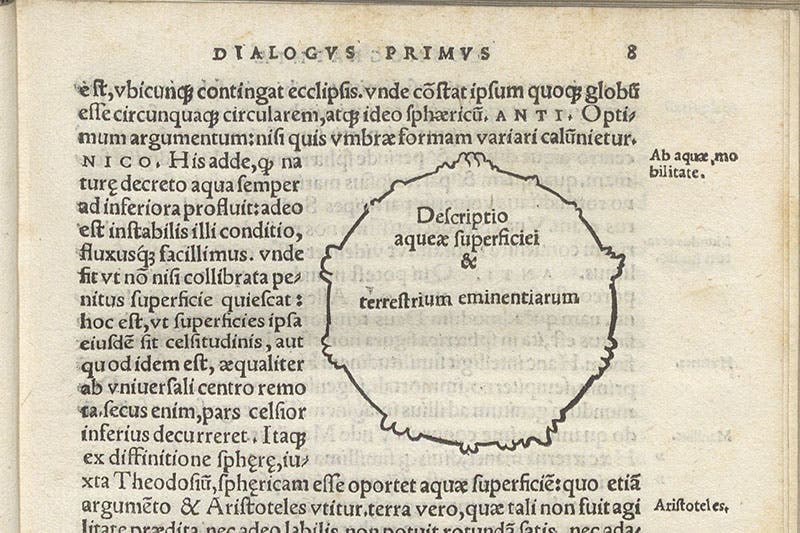

Maurolico also included a woodcut of an astronomical observing instrument called "Ptolemy's rule" (first image) which would become better known when Copernicus had one constructed for his own use, and then Tycho Brahe sent an assistant to Frombork to retrieve Copernicus’s instrument for his own observatory. And Maurolico’s section of the terraqueous globe, with its round mountains poking up above an undepicted sea, is charming, perhaps because I have never seen anything like it in a 16th-century book (sixth image).

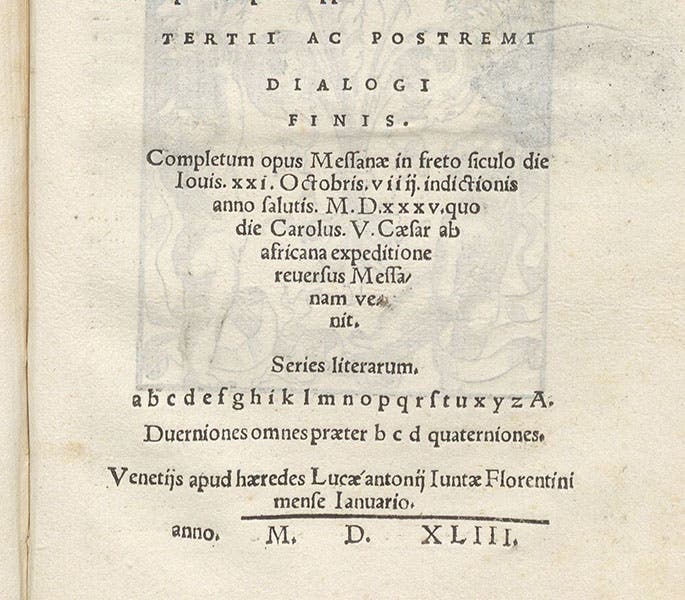

Maurolico dedicated his book to Pietro Bembo in Venice, who was quite pleased to be associated with it, and actually saw the manuscript through the press in Venice (you might check out our post on Bembo, if for no other reason than to see the gorgeous portrait of Bembo by Titian). As one (if one reads Latin) can see from the colophon (seventh image), Maurolico actually finished writing the book in 1535, just a day before Emperor Charles V arrived in Messina, so it took 8 years to get the manuscript printed. And then the book had the additional misfortune of appearing in the same year as the De revolutionibus of Nicolaus Copernicus. Maurolico assumed, as all had before him, that his "cosmographia" was earth-centered, not sun-centered. Maurolico never did warm to the Copernican system and died a convinced geocentrist in 1575.

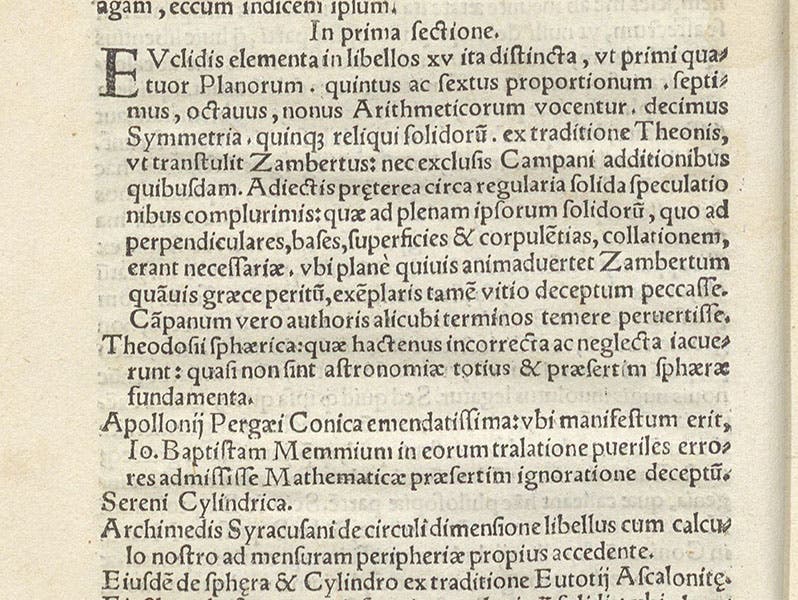

One of the most interesting features of Maurolico’s Cosmographia appears in the dedication to Bembo. Maurolico expressed his wish to reintroduce ancient Greek mathematics and astronomy to the world, and then listed no fewer than 67 books (!) that he would like to publish – all the work of Archimedes, Ptolemy, etc., with his own commentary and translation (eighth image). He must have been aware that Regiomontanus had compiled and printed a similar (but much shorter) list in 1474. Regiomontanus then died young, before he could print most of the books on his list. Maurolico lived much longer, but his list suffered a similar fate, as hardly anything on it would ever appear in print under his editorship.

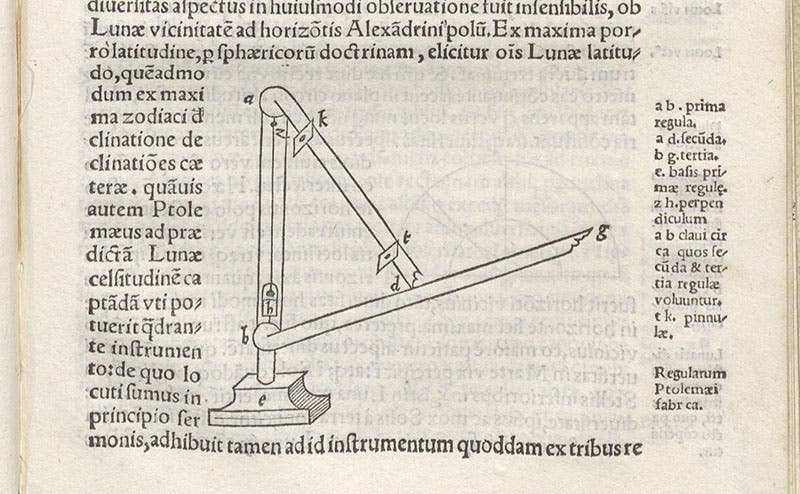

There is one portrait of Maurolico, an engraving by M. Bovis after a painting by Polidoro da Caravaggio, no relation to the more famous and later Caravaggio. I do not know if the original portrait survives anywhere, but I have never seen it reproduced. I used here the print in the Wellcome Collection in London (second image)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.