Scientist of the Day - Francesco Maria Grimaldi

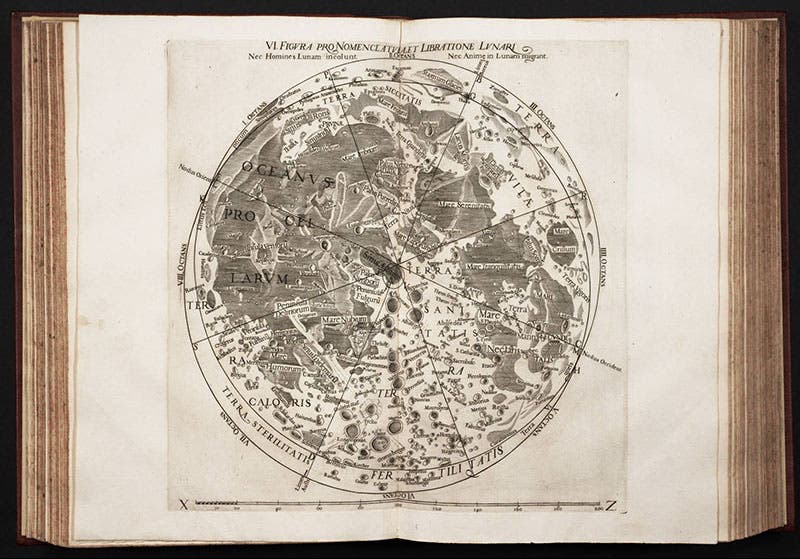

Francesco Maria Grimaldi, an Italian Jesuit, was born Apr. 2, 1618. A lifelong resident of Bologna, Grimaldi entered the Society of Jesus at age 14 and took an interest in the sciences, as did many Jesuits in that century. In the late 1640s, he produced a large and detailed map of the moon, based on his own observations. His fellow Jesuit and Bolognese, Giambattista Riccioli, then invented a naming system for the various craters and seas, and published Grimald's map with his own names in his Almagestum Novum (1651; second image). The map is especially noteworthy because Riccioli’s lunar nomenclature – one of several then available – turned out to be the one we still use. So the Sea of Tranquility (Mare tranquilitatis), where Apollo 11 landed, first appeared with that name on the Grimaldi/Riccioli map (first image).

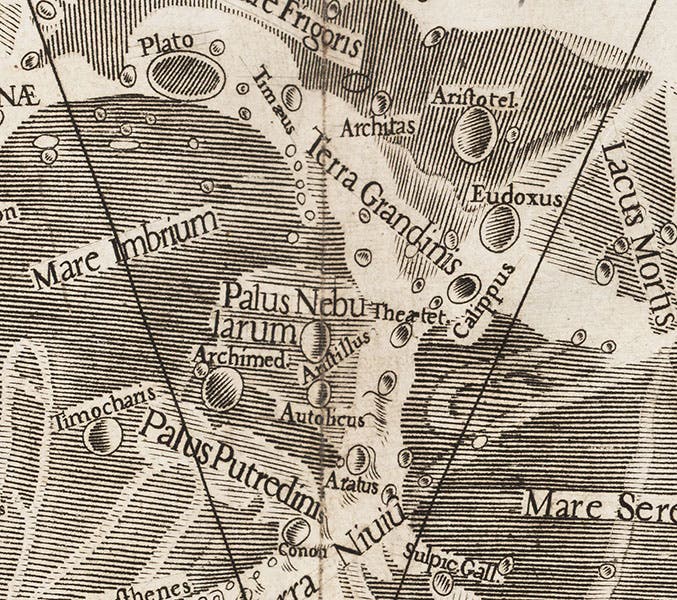

We show several other details here in order to make a few further observations about the map. The crater names were ordered so that ancient astronomers and philosophers were placed in the first two octants (at top left center and center); we can see Plato, Archimedes, and Aristotle in a detail of the top (third image). The maria (seas) were named after moods (tranquility, serenity) or meteorological phenomena (Mare frigoris – the Sea of Cold).

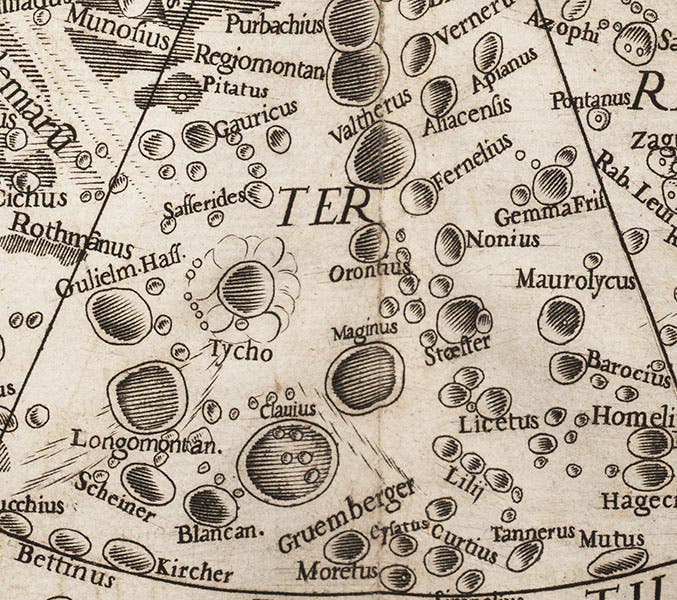

By the time Riccioli got around to the bottom octants, craters were being named after Renaissance and 17th century scientists. The most prominent crater in the south, the one at the center of the radiating rays, was named after Tycho Brahe, who proposed an earth-centered cosmology that was very popular among Jesuit scientists, since Copernicanism had been condemned. Accordingly, most of the craters to the south of Tycho, such as Clavius, Kircher, and Scheiner, were named after Jesuits (fourth image).

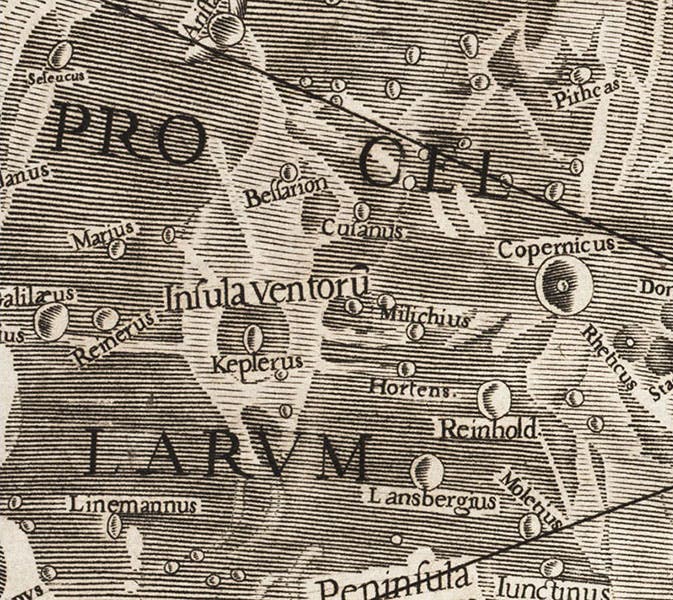

Riccioli said that he condemned Copernican astronomers to perdition by flinging them into the Ocean of Storms at left center, but the fact is that some of the most attractive craters on the moon are named after Copernicus and his followers, such as Kepler (fifth image).

We displayed the Grimaldi/Riccioli maps in an exhibition some years ago, The Face of the Moon: Galileo to Apollo, and it is on display again, right now, in our new exhibition, To the Moon: The Science of Apollo, which opened just last week.

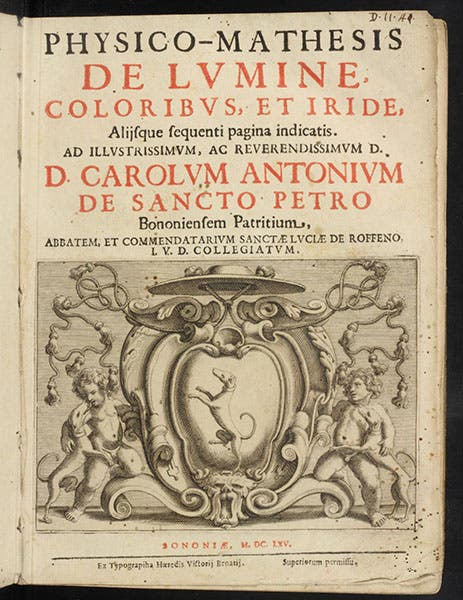

Among physicists, Grimaldi is best known for discovering the optical effect known as diffraction, whereby light, after passing by an obstacle such as a slit or pinhole, spreads out more than expected, to produce thin colored fringes. Diffraction would later be used, by Thomas Young and Augustin Fresnel, as a principal argument for the wave theory of light. Diffraction was first announced in Grimaldi’s posthumous Physico-mathesis de lumine (1665), which we have in our History of Science Collection (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.