Scientist of the Day - Francesco Fontana

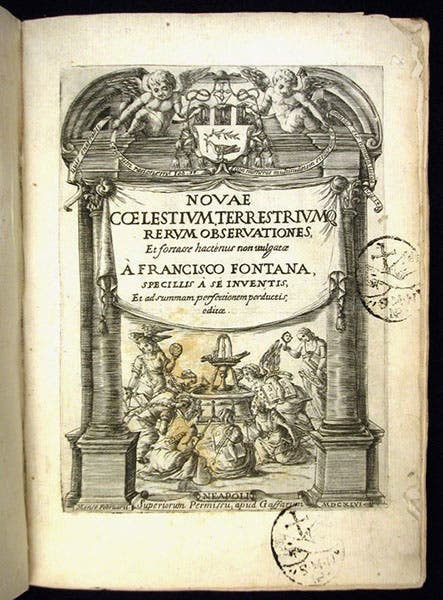

Francesco Fontana was a Neapolitan lawyer and telescope maker, with no known birth or death dates. He claimed to have made his first telescope in 1608, before Galileo, and to have invented what we now call the astronomical telescope, with two convex lenses, which provided an inverted image but a wider field of view than Galileo's telescope. There may be some truth to all of this, as others were using Fontana’s telescopes as early as 1614, although we have only Fontana’s word for the 1608 date. But there is no doubt that beginning in 1629, Fontana was making visual records of his observations of the Moon. Galileo had published his Sidereus nuncius in 1610, containing his drawings of the Moon, and there were a few other scattered published images of the Moon in the 1610s and 1620s. But no one undertook a continuous lunar observing program before Fontana. He soon branched out to observing and drawing Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. However, it was not until 1646 that he published a book containing all of his drawings, and when the magnificent Selenographia of Johannes Hevelius came out the next year, Fontana’s book was almost immediately relegated to the back shelf, and it has remained there, more or less, ever since.

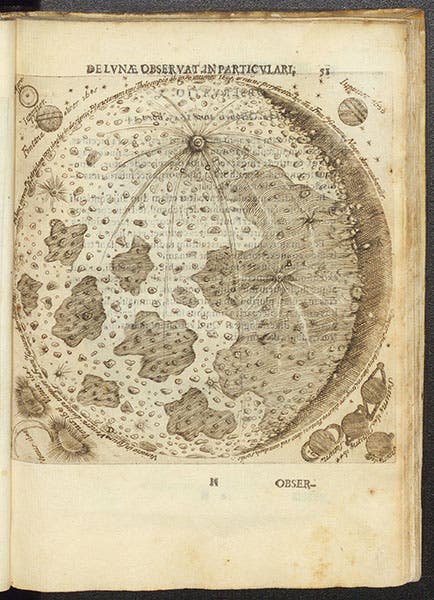

But Fontana’s book is worth a look, and we just happen to have a fine copy in our collections, in a venerable limp-vellum binding. The full title is Novae coelestium terrestriumq[ue] rerum observationes, et fortasse hactenus non-vulgatae (New observations of celestial and terrestrial things, perhaps never before published). It was the most richly illustrated astronomical book published to that time, with 27 etchings of the moon and 26 woodcuts of other astronomical bodies. The etchings show almost the complete range of lunar phases, which no one had done before. He included the 1629 etching of the Moon in his book, and two from 1630, but most of the rest were made late in 1645. To his credit, Fontana provided, for nearly every drawing, the exact day and hour that it was made, usually on a facing page. We show a waning moon, observed Oct. 5, 1645 (fourth image).

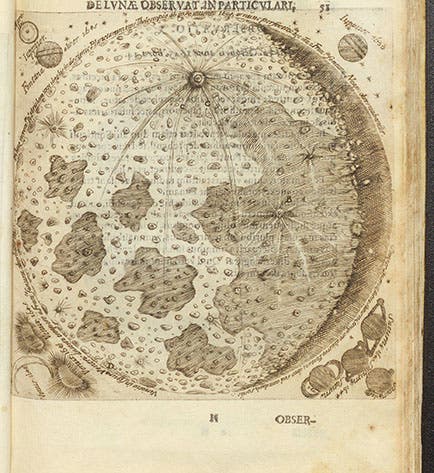

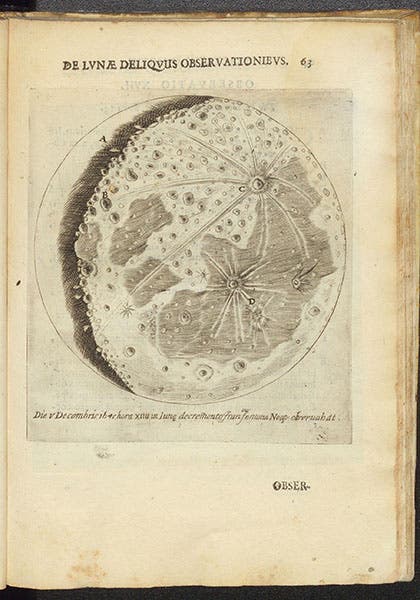

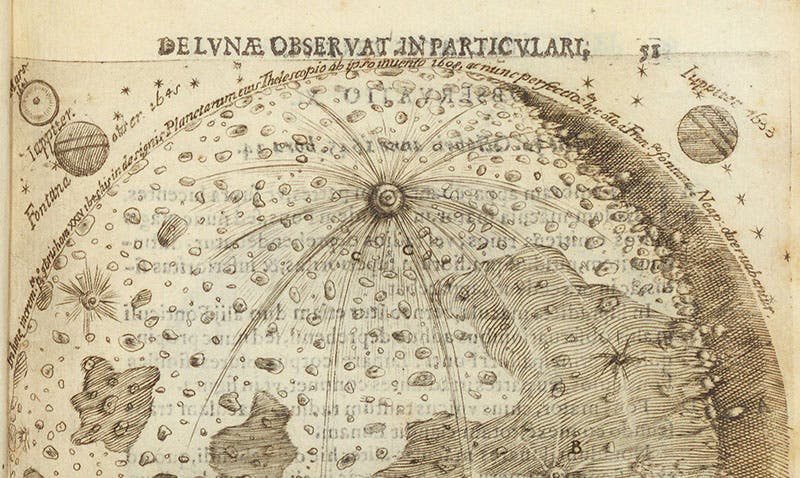

There is only one lunar drawing that is undated, because it seems to have been some sort of advertisement, first printed separately perhaps, showing not only a lunar map, but in the four corners, drawings he had made of the other planets (first image). There are small inscriptions circling the moon, but the one at the top is of special interest, for here he claims to have invented his telescope in 1608 (see detail, fifth image). Notice the rays emanating from what will be named the crater Tycho and reaching across the entire visible face of the moon. This is something you can only see at full Moon, and Fontana was especially good at capturing these.

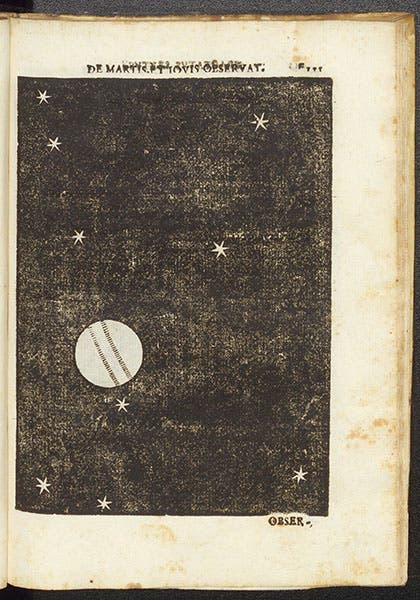

The views of the five planets in the corners of our first image are tiny, but there are larger ones in the last half of the book. These are woodcuts, not etchings, and because many of them are mostly black, they often show through the page, which can be unsightly, and sometimes a little confusing.

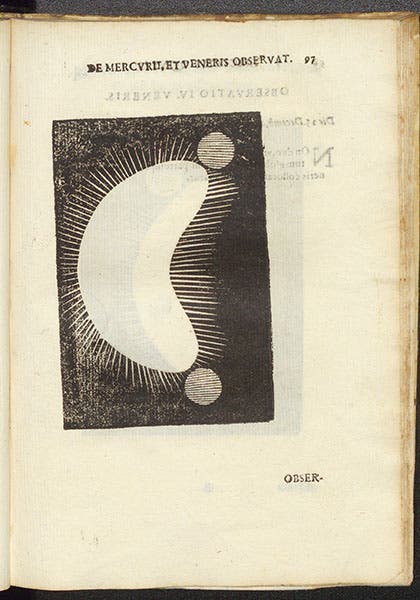

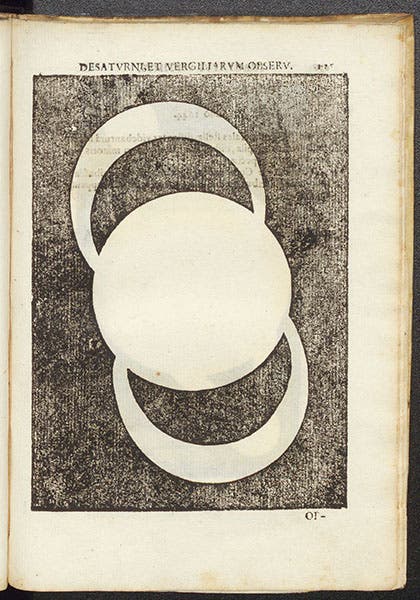

Most of Fontana’s woodcuts do not sure real planetary features, except for Jupiter, whose belts were nicely drawn by Fontana and and appeared in 8 woodcuts covering a dozen years (sixth image). Venus was so bright that it frazzled his vision, and the Venuses he drew (6 of them) were not only sparkly, but adorned with one or two moons, which are not actually there (seventh image). There are 7 woodcuts of Saturn, of which we show only one (eighth image). Each Saturn is different, and we can understand why astronomers were so confused about the "anses" or handles of Saturn, before Christiaan Huygens figured it out in 1656.

Fontana's book did not have the impact it might have created, had Hevelius stuck to brewing beer. But Giovanni Battista Riccioli included many of Fontana’s drawings of Venus, Mercury, and Mars in his Almagestum novum (1651), which gave Fontana some attention, even if Riccioli then proceeded to blow Fontana’s moon drawings out of the water with his (and Francesco Grimaldi’s) own lunar map.

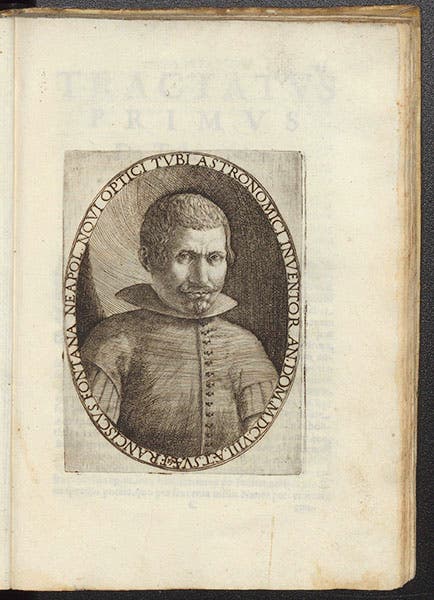

The only portrait of Fontana of which I am aware is the one included in his Novae coelestium, an etched self-portrait (second image). Recently a scholar has argued that Jusepe de Ribera’s allegorical painting of Sight (1616, in the Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City, ninth image) might portray Fontana, and when one compares the painting to the self-portrait, it certainly seems to be a possibility.

Fontana died, along with his entire family, during an outbreak of the plague in about 1656; we have no idea how old he was at the time of his death. The Novae coelestium was his only publication.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.