Scientist of the Day - Francesco Calzolari

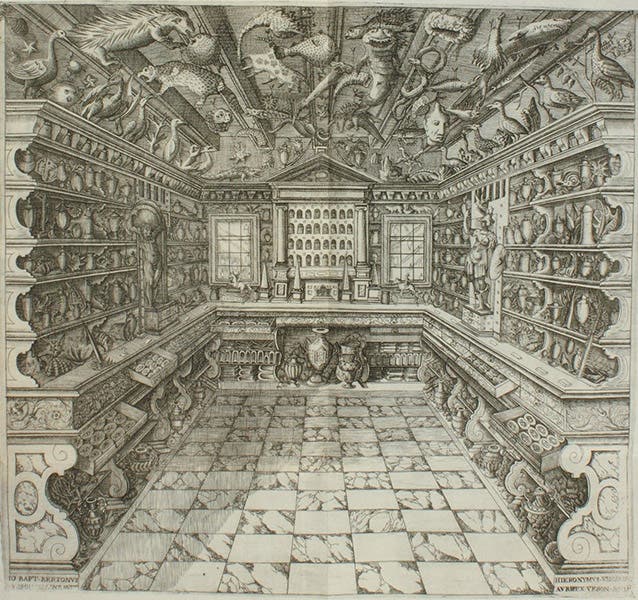

The museum of Francesco Calzolari, folded engraved frontispiece to Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii, by Benedicto Ceruto and Andrea Chiocco, 1622 (Linda Hall Library)

Francesco Calzolari, an Italian apothecary and collector of natural objects, was born July 10, 1522, in Verona. He was known for his vast knowledge of the Veronese flora (most of the preparations sold by apothecaries were herbal in origin), and for the collecting excursions he led up nearby Monte Baldo. He was also renowned for his preparation of theriac, a universal remedy for most human ailments, concocted from over 60 ingredients, of which the most notable came from freshly-killed vipers. The making of theriac was an annual ritualized ceremony in most Italian cities and towns, and Calzolari's in Verona was one of the most famous.

But we write today about Calzolari's museum. Museums, or Wunderkammern, or cabinets of curiosities, were already fairly common by the mid-16th-century, but they tended to be the collections made by kings, princes, and wealthy citizens, and they contained mostly exotica – rare objects, or monstrous objects, or natural objects that were decked out with artisanal embellishments, such as silver drinking cups made from ostrich eggs.

Engraved title page, Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii, by Benedicto Ceruto and Andrea Chiocco, 1622 (Linda Hall Library)

Calzolari also collected things, but they tended to be natural objects exclusively, and they were not exotic, but rather the ordinary plants and animals that one might use in preparing medicines. The one thing he shared with the rich collectors such as the Habsburgs was the desire to display his collection to visitors. No matter what kind of museum one had, it wasn’t really a museum unless it could be seen by the public.

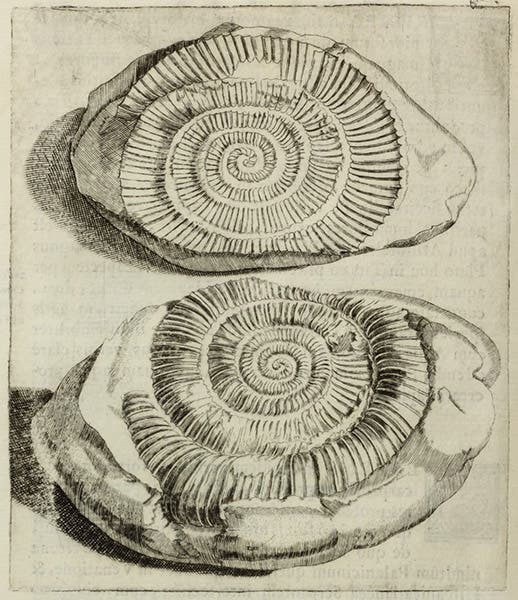

A fossil ammonite in its matrix, text engraving, in Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii, by Benedicto Ceruto and Andrea Chiocco, 1622 (Linda Hall Library)

Calzolari also wanted to publish a catalog of his museum. In 1580, there were no museum catalogs in print. There were inventories, naturally, but no one had thought it desirable to discuss his collection in a published work. Calzolari’s first attempt came in 1584, but that catalog was not much more than an inventory, and it had no illustrations. Calzolari set his sights on something far more encompassing.

He was beaten to the finish line by another apothecary, Ferrante Imperato of Naples, who published his museum book in 1599. Calzolari’s illustrated museum catalog would not appear until 1622, well after his death in 1609, when his grandson (Francesco Jr.) commissioned two physicians, Benedicto Ceruto and Andrea Chiocco, to prepare a description of the items in the still existing collection and to commission illustrations of selected objects. We have their publication, Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii (1622), in our collections.

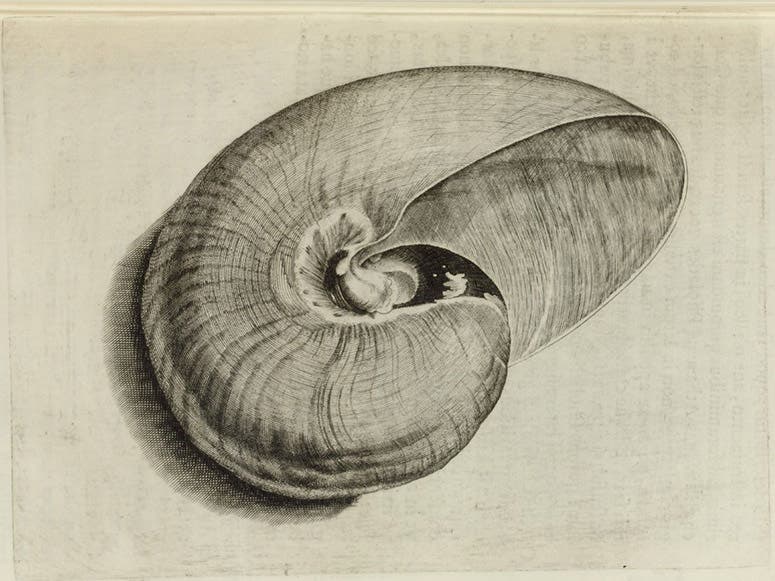

Pearly nautilus shell, text engraving, in Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii, by Benedicto Ceruto and Andrea Chiocco, 1622 (Linda Hall Library)

Our copy is a large quarto, bound in limp vellum, illustrated with many text engravings, which I have not counted, but there are at least 40 of them. Using text engravings to illustrate a book like this is a difficult and expensive process, since a page with both text and image must be printed twice, on two different kinds of presses. But if one can afford it, the result is well worth the bother, for the images are much sharper and more detailed than the woodcuts that were ordinarily used (such as in Imperato’s museum book of 1599).

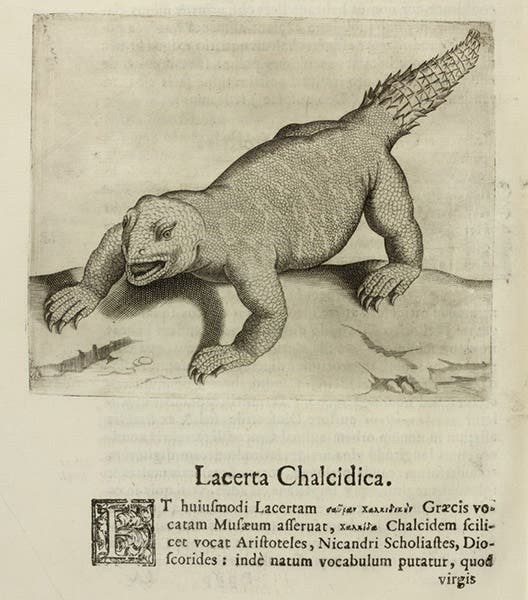

Lacerta chalcidica or terrestrial crocodile, text engraving, in Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii, by Benedicto Ceruto and Andrea Chiocco, 1622 (Linda Hall Library)

The most intriguing engraving is the first, a folding frontispiece that shows the entire museum set up for display (first image) This would become a commonplace for later museum books, and was not invented by Ceruto or Chiocco or Calzolari, but by Imperato, who had a similar folding woodcut showing his museum in his catalogue of 1599. Imperato also included the host (himself) and some visitors in his illustration, a necessary part of any museum, an innovation which for some reason was not followed in the Calzolari engraving, but which reappeared in the depictions of the museum of Basil Besler (which we show in our post on Besler) and many later engravings of museums. Interestingly, Ole Worm did not populate his museum with people either (see our post on Worm). We have not yet written a post on Imperato, but you can see his precedent-setting woodcut here.

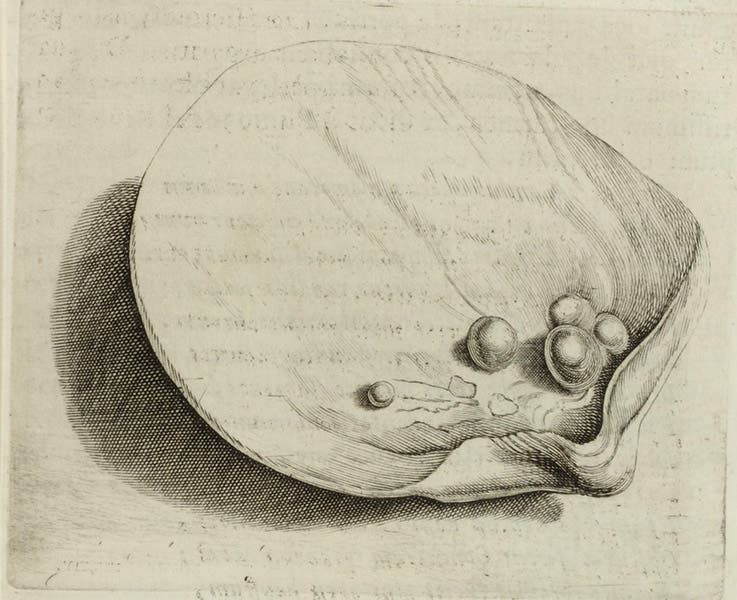

Oyster with pearls, text engraving, in Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii, by Benedicto Ceruto and Andra Chiocco, 1622 (Linda Hall Library)

But the text images in the Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii more than make up for any shortcomings in the frontispiece, for they are beautiful and dramatic, and the eye is immediately drawn to them. We show a fossil ammonite still in its matrix in our fourth image, followed by a pearly nautilus shell, not a fossil but the shell of a still-living species (fifth image). The specimens described were organized into several large classes, with the ammonite in the section on fossils and the nautilus in the section on seashells. The authors do not suggest, nor should they have in 1622, that the nautilus is a living descendant of the extinct ammonite.

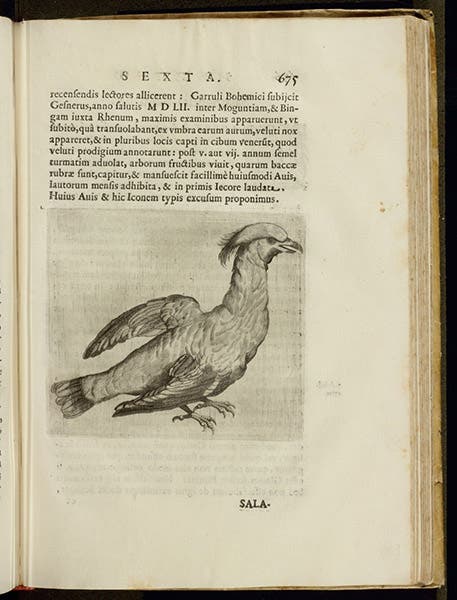

A Bohemian waxwing, text engraving, in Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii, by Benedicto Ceruto and Andrea Chiocco, 1622 (Linda Hall Library)

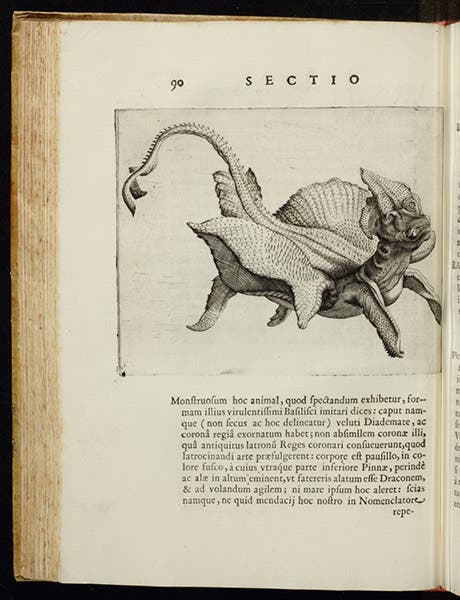

The other images depict: a Lacerta chalcidica or terrestrial crocodile (sixth image); an oyster with pearls (seventh image); a Garrulus bohemicus or Bohemian waxwing (eighth image). The last image shows something a big different – a Jenny Haniver, as they will later be called, which were skates or rays that had been scissored into shapes that resembled dragons. Every museum had one, and Calzolari’s was no exception.

“Jenny Haniver,” a ray modified to look like a dragon, text engraving, in Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii, by Benedicto Ceruto and Andrea Chiocco, 1622 (Linda Hall Library)

The museum will undergo many transformations in the 17th and early 18th century, until it eventually comes to resemble the modern natural history museum. The most important steps were the first two, taken by Calzolari and Imperato: expanding the objects in collections from exotica and mirabilia to include specimens from the ordinary course of nature, and producing catalogs, preferably illustrated ones, to explain the objects on view. Ole Worm’s Museum Wormianum (1655) and Nehemiah Grew’s Museum regalis societatis (Museum of the Royal Society [of London], 1681) would have been unimaginable without the precedent of the Musaeum Franc. Calceolarii.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.