Scientist of the Day - Frances Glessner Lee

Frances Glessner Lee, a pioneer of forensic medicine in the United States, was born Mar. 25, 1879, in Chicago. Her father was one of the founders of International Harvester and made a fortune that Frances would inherit, allowing her to do whatever she wanted, which, for the first 45 years of her life, wasn’t much. The family had a mansion that father George built, on Prairie Avenue in Chicago, and also a large summer home, The Rocks, just west of the White Mountains in New Hampshire. But in the late 1920s, Lee discovered her mission in life, which was to reform the way crimes, especially murders, were investigated. Nearly all police departments nationwide relied on coroners instead of medical examiners to determine cause of death, and coroners had no medical background. Nor did police investigators normally have any medical training. Frances’ brother George went to Harvard, and his best friend, George Magrath, attended Harvard Medical School and became a forensic pathologist. Frances was a close friend of Magrath as well, and when Magrath fulminated about the non-existence in this country of a system of medical examination of crime scenes, Frances took heed, and discovered what she wanted to do for the rest of her life – help establish a new kind of medicine, legal or forensic medicine.

Much of Lee's assistance came in the form of money. She endowed Harvard's new Department of Legal Medicine in 1931, and their library, and paid for twice-yearly police seminars at Harvard, where state police investigators from all across the country were taught the essentials of crime scene investigation.

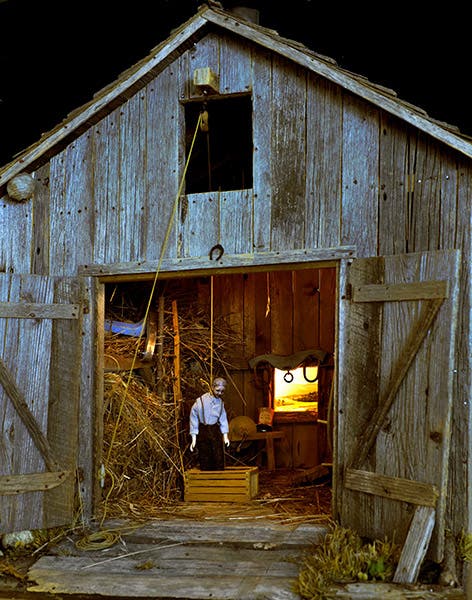

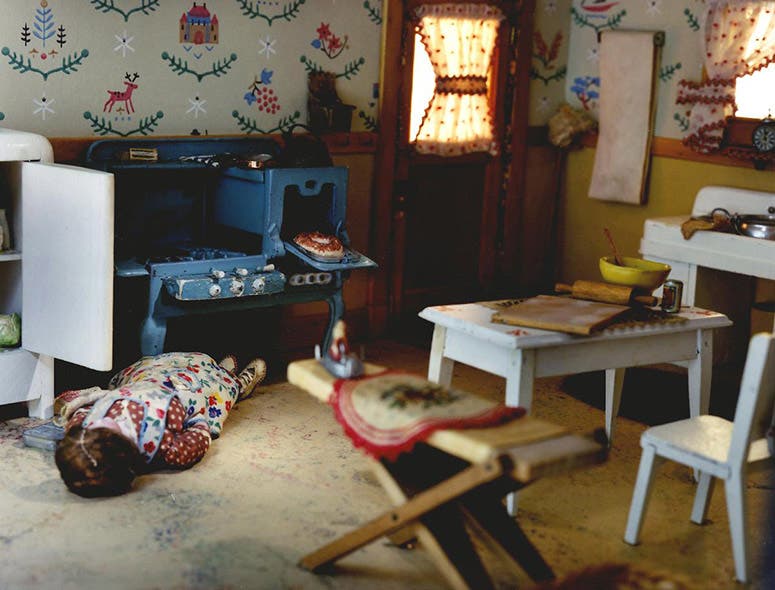

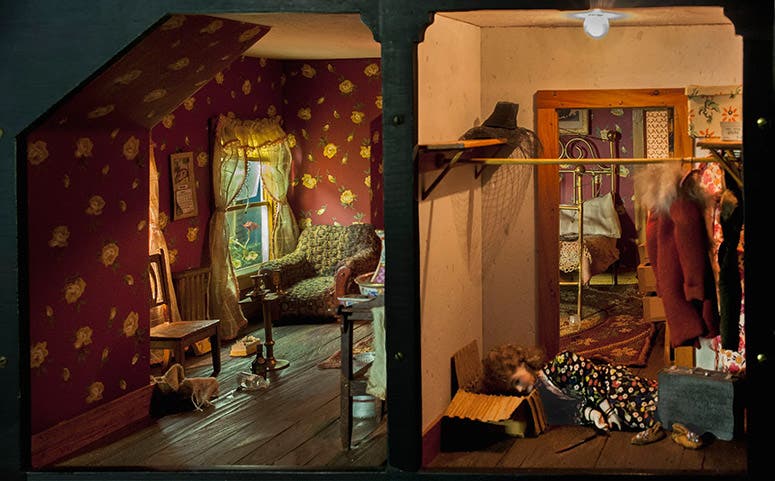

But Lee is remembered mostly for her Nutshells, or, in full, Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. Built by her from 1944 to 1948, these consisted of 20 doll-house-scale dioramas, each of them capturing a murder scene in excruciating and bloody detail. They had names like Three-Room Family, Barn, Dark Bathroom, Burned Cabin, and Woodman’s Shack. They were intended for use in teaching crime-scene investigation at the Harvard seminars.

Lee had built several elaborate dioramas when she was younger, most notably a doll-house-(1 to 12)-scale model of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, of which her father was a primary benefactor, and which often played at the family mansion in Chicago. Lee took great pains to capture the personal traits and postures of each of the 100+ orchestra members, to the delight of them all. But at that time, 1913, Lee was just a social gadfly. Now, thirty years later Lee wanted to build miniatures with a purpose.

Normally, Lee contributed primarily financial support for her causes. The Nutshells were different, in that Lee was personally involved in constructing them. Teaching investigators how to examine an actual crime scene was almost impossible, since the evidence was easily corrupted, and time was short. Lee thought that models of crime scenes would be ideal for instruction, if they were realistic and detailed, because the details would never decay. And she thought she could make dioramas perfectly suited for the purpose she had in mind.

So she built dioramas of 20 different murder scenes. Each depicted a crime scene as it would have appeared to the first investigator to arrive. They involved stabbings, hangings, strangulations, and deaths with causes yet unknown. Each scene was meticulously detailed. Much of the initial work was done by the carpenter at The Rocks in New Hampshire, the family summer home that was now her permanent residence. Lee attended to the details herself, making wallpaper, knitting tiny socks and sweaters, sewing clothes, writing tiny manuscripts, and labeling kitchen items. When she began the project, in 1944, obtaining materials, especially metals, was very difficult, due to Wartime rationing. But she always found a way to get what she needed. The realism achieved is extraordinary. The Nutshells were built between 1944 and 1948, and were put to immediate use at the Harvard seminars. An attendee would have 90 minutes to study a diorama, listing and interpreting the clues. Each scene, based on a real murder, was complicated with seeming inconsistencies. Solutions to the murders were kept in a safe, and still are. But solving them was not the purpose. The goal was to learn how to observe.

The Nutshells were used at Harvard until 1966, then transferred to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Baltimore, where they are still in use for an annual seminar. Eventually they were recognized as works of art in their own right, and in 2017, the 18 surviving dioramas were made the subject of an exhibition at the Renwick Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. This was really the first time that Frances Lee came to the attention of a wider public (and the first time the dioramas were properly photographed). I wish I had known about Lee then, and had been able to visit the exhibition of her dioramas.

There is an excellent biography of Lee, called 18 Tiny Deaths: The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics (Sourcebooks, 2020), by Bruce Goldfarb, which was my primary source for this post. You may find the book in our Library.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.