Scientist of the Day - Fra Mauro

Fra Mauro, a Venetian monk and cartographer, was born around 1400 and died about 1460. He was a member of the Camaldolese order of hermits and lived in the monastery of San Michele on the island of Isola, between Venice and Murano in the lagoon of Venice. He made maps for the monastery, or rather, ran a map-making workshop at San Michele. The only date we have for Fra Mauro is the date, “Aug. 26, 1460”, which is written on the back of his greatest creation, the Fra Mauro world map. Today, on Aug. 26, we celebrate Fra Mauro and his map.

The Fra Mauro world map has been often described as the last great medieval map, although it could more accurately be characterized as the first modern world map, since there is little medieval about it, except for some the information that Fra Mauro incorporated on his map. It is larger than you might think from photos, being over two meters across, almost 8 feet square in its frame. It is oriented with south at the top, which was different from Ptolemaic maps, which showed north at the top, or from medieval mappae mundi, which usually had east at the top. The orientation of the Fra Mauro map may reflect the influence of Islamic cartographers, who often put south at the top. Since most of us do not recognize the world upside down, I have inverted the map in the second image, so you can see how good the map was, especially in showing the west coast of Africa, which did not appear on any of the maps of Ptolemy of Alexandria. I also include an inverted section showing Italy, Greece, and the Mediterranean Sea, so you can appreciate how accurate this part of the map was (third image).

The Fra Mauro map is a manuscript map, meaning the map and all of the text was painted or written in by hand. The surface is fine vellum, backed by wood. There were originally two nearly identical maps. This one was found in the monastery of San Michele and moved to the Marciana Library in Venice; the other was made in 1459 for the King of Portugal and was delivered, but disappeared sometime before the end of the 15th century and has not been seen since.

Scholars have had a great time trying to figure out where Fra Mauro got his information, since much of it had never appeared on a world map before. Marco Polo is there, in abundance – most of the isles in the Far East were mentioned in Marco Polo's account of his travels. The travels of Fra Mauro’s near contemporary, the merchant Niccolò de' Conti, appear to have been a source, and historians guess that Fra Mauro would have been privy to a great deal of oral information from travelers and merchants, since Venice was a world hub at the time. There are more than 3000 banderoles on the map, chock full of information on Russia, southeast Asia, China, even Cipangu, as Japan was called at the time. You can see some of these in the details that show Taprobana (fourth image) and Mesopotamia (fifth image).

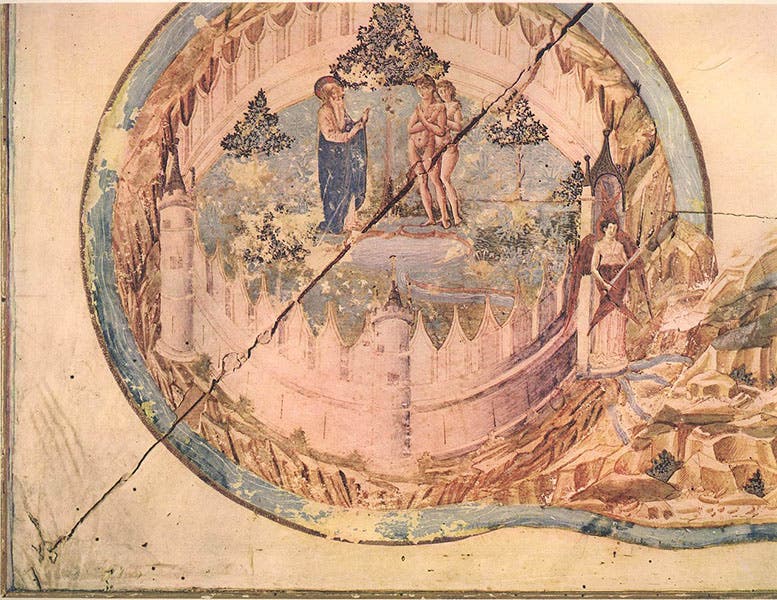

It was customary for medieval world maps to place the Garden of Eden or Jerusalem at the center. Fra Mauro removed Eden from the map entirely and showed it as a vignette at bottom left (sixth image). That was a significant departure from tradition, especially for a monk. We surmise that Fra Mauro was a worldly monk, in all senses of the word.

I have never seen the Fra Mauro map in person, and would love to. It is often described as being in the Marciana Library in Venice, but I believe it is on display at the Correr Museum on St. Mark's Square in Venice. There is an 18th-century replica in the British Library, which is supposed to be quite accurate, but still, it is a replica, which is not the same thing. A better choice to look for would be the fully zoomable version on the website of the Galileo Museum in Florence, which allows you to read every word of text. This is a remarkable piece of digital magic, and the associated webpages contain an abundance of additional information on Fra Mauro and his map. You may access it here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.