Scientist of the Day - Fortunio Liceti

Fortunio Liceti, an Italian natural philosopher, was born Oct. 3, 1577, near Genoa. He was educated at the University of Bologna, studying philosophy and medicine. If he interacted at all with Ulisse Aldrovandi, the great Bolognese naturalist who published the first volume of his Natural History while Liceti was there, we do not know. We do know that Liceti taught at Pisa for a few years and then moved on to Padua in 1609, the same year that Galileo made his first celestial observations with his telescope, and where Liceti became professor of philosophy. The two interacted for a year, before Galileo left for Florence. Liceti sat in that chair until 1637, when he accepted an invitation to teach in Bologna. He returned to Padua as professor of medicine in 1645 and remained there until his death in 1657.

Liceti was a prolific author, writing books, in the words of historian John Heilbron, faster that most people could read them. He was an Aristotelian, meaning that he did not accept the heliocentric cosmology of Nicolaus Copernicus, and he liked controversies, so when three comets appeared in 1618 and the Jesuits and Galileo began to argue about whether the comets were sub-lunar (and thus not heavenly) or truly celestial, out there with the planets, Liceti jumped in on the side of Aristotle with several treatises on comets (one of which we own), arguing that comets are part of the sphere of fire and are not out beyond the moon. In this, he disagreed with Galileo, with whom he would engage in many disputes, all of them, however, reasonably amicable (unlike most of Galileo’s intellectual disagreements, which could get quite testy).

One of Liceti’s more interesting controversies with Galileo began in 1640, when Galileo was quite old (76) and restricted to his house in Arcetri, near Florence, after being sentenced to house arrest by the Inquisition in 1633. Galileo had also lost his sight by this time. Since we have both of the Liceti books involved in this disagreement, we will discuss it in more detail.

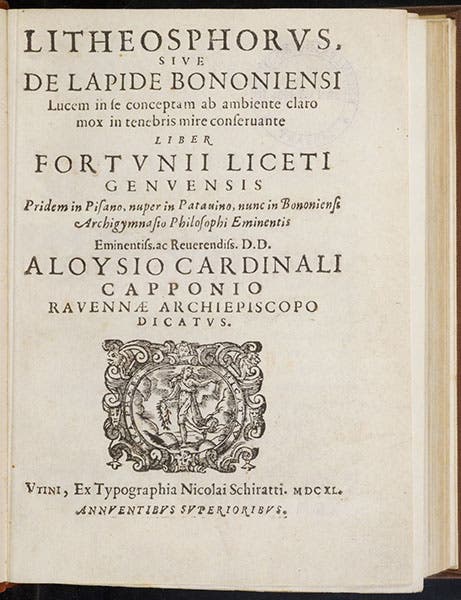

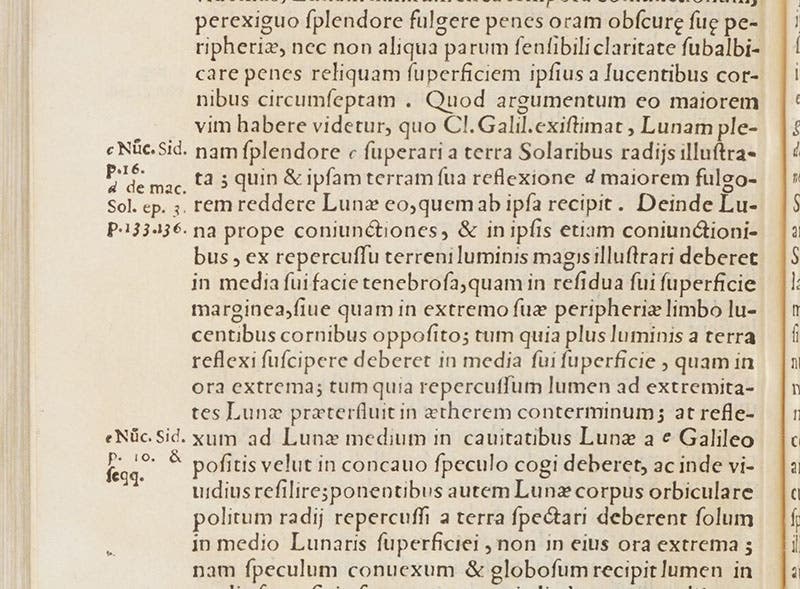

Liceti, having moved back to Bologna, became aware of an object (really, a phenomenon) called the "Bologna stone". A mineral found on the outskirts of Bologna, which we now call barite, had been recently discovered to have the property of glowing at night, after (it was presumed) being exposed to the rays of the Sun during the day. Liceti, as was his wont, immediately wrote a book on the Bologna Stone, which he called Litheosphorus, sive, De lapide Bononiensi (1640). Near the end, he proposed a new explanation for what Galileo had called earthshine in his Sidereus nuncius (1610). Galileo had suggested that the faint glow of the Moon, when it was supposedly in shadow, came from the reflection of sunlight from the Earth, just as the Earth receives reflected light from the Moon. Liceti seized on the Bologna stone to provide a different explanation. It was possible, he said, that the Moon absorbed sunlight during the day, just like the Bologna Stone, and released the stored sunshine at night, producing its faint glow. In the next-to-last chapter of his book, where he gently attacks Galileo's explanation, you can see several references to the Sidereus nuncius in the margin of one of the pages (third image).

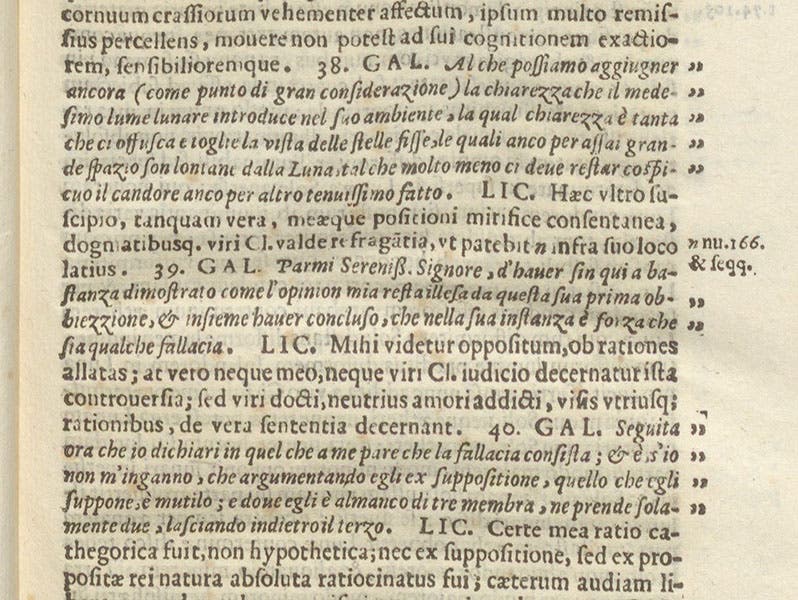

Galileo received a copy of Liceti's book (I am guessing that Liceti sent him a copy), and Galileo immediately wrote a long letter to the Medici prince, Leopoldo, the brother of the Duke of Florence. Actually, he dictated the letter to Vincenzo Viviani, his assistant, since he could no longer see to write. Liceti complained that he should have received the letter, so Galileo sent him a copy (removing some of his more impolite comments). Liceti then wrote an entire follow-up book, which he called De lunae subobscura luce prope coniunctiones (1642), in which he extracted 51 passages from Galileo's letter, quoted them in his book, and then responded to each of them, point by point. We see on one of the pages (fifth image) several extracts from Galileo's letter, denoted by the lead phrase GAL, the Italic font, and the quote marks in the margin, and then the more extended comments by Liceti, or LIC.

Licteti’s book turns out to be especially significant in Galilean studies, because Galileo's letter (disjointed though it might have been in Liceti’s printing) turned out to be Galileo’s last published work, as he died the year the book came out, in 1642. We bought our copy of Liceti's De lunae subobscura in 2017 from Rick Watson, the highly respected London rare-book dealer who retired from the trade just last year. We acquired many fine books from Rick, and we will miss him and his offerings.

There is a statue of Liceti in Padua, in the large city square, the Prato delle Valle (sixth image). There is a statue of Galileo on the same square. Never having visited the square, I do not know how far apart the two statues are. I hope they are close enough to each other that they can continue their bickering, albeit in a stonier fashion than before. I wonder if Liceti’s statue glows in the dark, after the Sun goes down, and whether some of that light falls on the statue of Galileo.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.