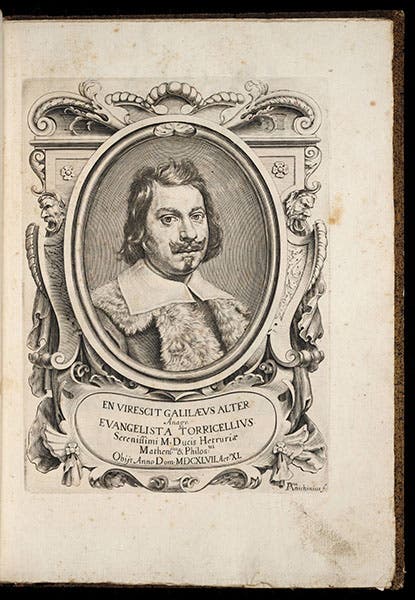

Scientist of the Day - Evangelista Torricelli

Evangelista Torricelli, an Italian physicist, died Oct. 25, 1647, at the age of 39. Torricelli studied mathematics and physics in Rome with Benedetto Castelli, who was in turn a student of Galileo. Torricelli wrote a short treatise on projectile motion, De motu gravium, that Castelli showed to Galileo, resulting in an invitation to Torricelli from the aged Florentine physicist. Torricelli did not make it to Florence until 1641, and he spent just three months with Galileo before he died, but Torricelli so impressed his mentor and his patron that he was invited to succeed Galileo as mathematician to the Medici court. Torricelli’s treatise on motion was published in his Opera geometrica (1644), which we have in our History of Science Collection.

Portrait of Torricelli, from Lezione accademiche (1715) (Linda Hall Library)

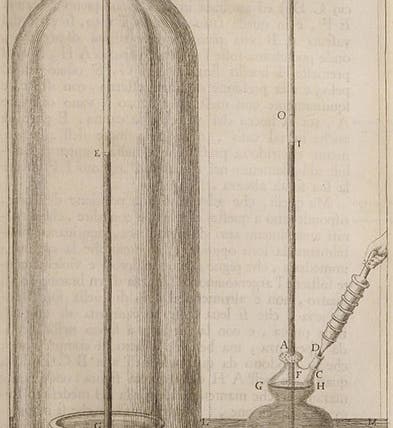

In 1644, Torricelli invented what we now call a barometer. Galileo had been asked by Ferdinando II d' Medici why the pumps for his fountains could not raise water any higher than 32 feet. Torricelli took up the problem after Galileo's death; he experimented with a much denser liquid, mercury, and discovered that mercury could not be raised any higher than about 30 inches. Further, he found that if you inverted a 3-foot tube filled with mercury into a bowl, the mercury ran out of the tube into the bowl until the mercury column stood at 30 inches. Although Torricelli understood that the level of mercury fluctuated with the weather, that was not his primary concern, so we tend to call his invention a “Torricellian tube” rather than a barometer. Torricelli was interested, first, in what keeps the 30 inches of mercury up in the tube, and, second, what is above the mercury, in the closed end of the tube. Torricelli suspected that the weight of the atmosphere keeps the mercury up - that we live under an "ocean of air", as he put it, and that there is a vacuum at the top of the tube. Considering that, in 1644, when he announced his discovery in a letter to a friend, air was thought to be naturally light, without weight, and that a vacuum was thought to be a physical impossibility, Torricelli's tube was an eye-opener and a thought-provoker and, as it turned out, a world-changer. Subsequent experiments by Blaise Pascal and others confirmed that Torricelli was right about the atmosphere having weight, and that there is indeed a vacuum at the top of the tube. Nature does not abhor a vacuum after all.

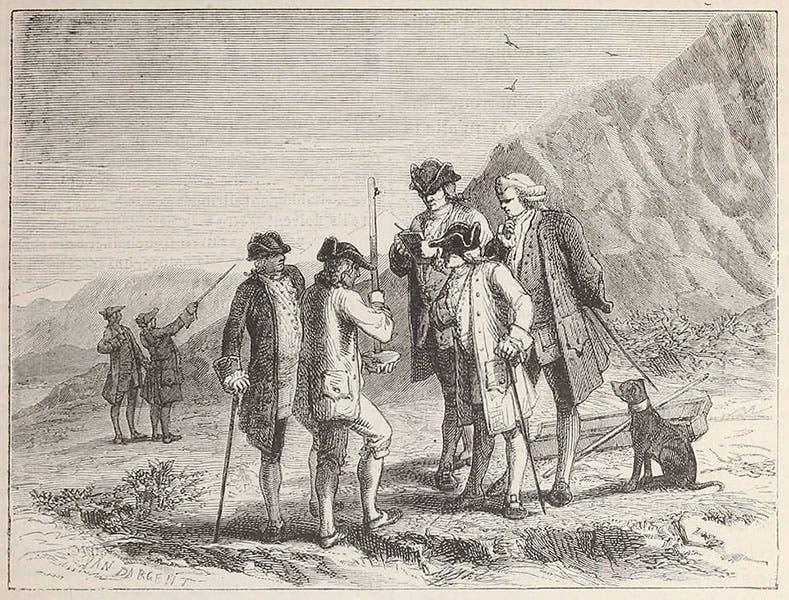

Torricellian tube being carried up a mountain, from Louis Figuier, Merveilles (1867) (Linda Hall Library)

Torricelli died before he could publish a treatise on his invention and its import. His remaining papers and letters would not appear in print until his Lezione accademiche was published in 1715, a work that we also have in our collections. That book is the source for Torricelli’s portait that we show here, but there are no other relevant images in either of his books. The engraving of the two Torricellian tubes (first image) comes from the Saggi of the Cimento Academy (1667). Our third image, really the best image we have of a Torricellian tube in use, appeared in Louis Figuier's Les merveilles de la science (1867), where it illustrated an account of Pascal's arranging to have a Torrricellian tube carried to the top of the Puy de Dôme in France. Figuier also included a seldom-reproduced image of Ferdinando asking Galileo why his pumps won't raise water 40 feet, and for want of others images of Torricelli to show you, we include it here (fourth image).

Duke Ferdinando II asking Galileo about pumps, from Louis Figuier, Merveilles (1867) (Linda Hall Library)

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.