Scientist of the Day - Ether Dome

On October 16, 1846, the first successful public demonstration of surgical anesthesia took place in the operating theater of Massachusetts General Hospital. As a skeptical audience of physicians and medical students watched from the sidelines, Dr. John Collins Warren removed a tumor from the neck of Boston housepainter Edward Gilbert Abbott. Throughout the procedure, Abbott inhaled vapors from a sponge soaked in sulfuric ether, which were administered by a local dentist named William Morton. Under the influence of Morton’s gas, Abbott sat motionless as Warren made a three-inch long incision beneath his lower jaw.

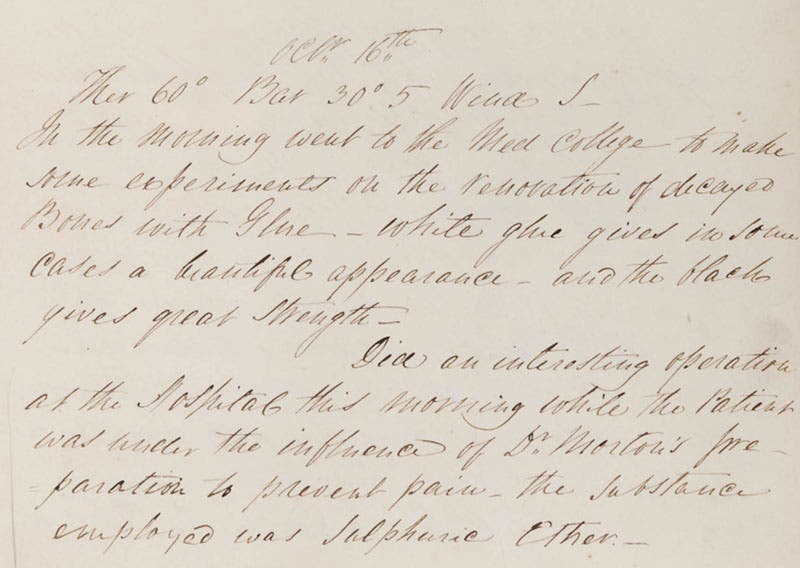

Abbott’s lack of reaction stood in stark contrast to another surgical demonstration conducted in the same amphitheater the previous year by Morton’s former business partner, Horace Wells. Wells had sought to demonstrate the painkilling properties of nitrous oxide, but the Boston crowd dismissed his claims when his patient emitted an audible groan in the middle of a tooth extraction. Other than some occasional muttering, however, Abbott barely stirred until his operation’s conclusion. At that point, Warren turned to the crowd. “Gentlemen,” he exclaimed, “this is no humbug.” Later that evening, Warren also wrote a brief journal entry describing this “interesting operation” (second image)

Everyone in the operating theater that October morning recognized the significance of what had just occurred. For centuries, surgery had been a messy, violent business carried out with the utmost speed. Suddenly, thanks to Morton’s new treatment, it became possible to envision a world where surgeons could operate more methodically and without inflicting pain on their patients.

Abbott’s surgery was not the first use of anesthesia—a term coined later by physician and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. Despite his apparent failure in Boston, Horace Wells had previously carried out numerous operations with nitrous oxide. In addition, it later became known that a physician in Georgia named Crawford Long had conducted several surgeries using ether in 1842, four years before Morton’s demonstration. Such details did not prevent Morton from asserting that he deserved sole credit for the invention of anesthesia.

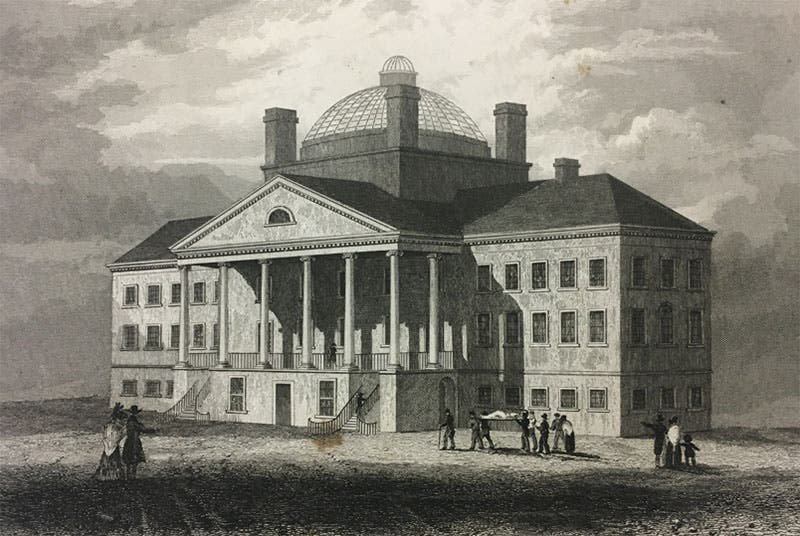

Regardless of these priority disputes, October 16, 1846 marked the moment when the broader medical community began to embrace anesthesia as a viable surgical technique. October 16 soon became known as “Ether Day,” and the operating theater at Massachusetts General, which remained in active use until 1867, was nicknamed the “Ether Dome” (third image).

Engraving of Massachusetts General Hospital, c. 1831. The building was designed by Charles Bulfinch, and the operating theater was located under the central dome, later known as the “Ether Dome.” (Clendening History of Medicine Library)

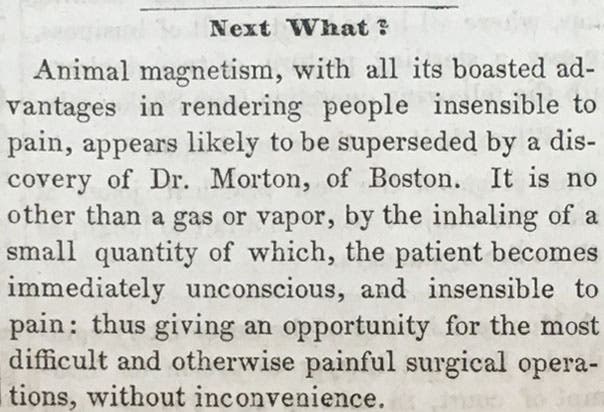

Although the Linda Hall Library does not actively collect material related to the history of medicine, our holdings do include the first nationally circulated article about the use of anesthesia. The piece in question was published in the October 17, 1846 edition of Scientific American (fourth image) and presented Morton’s ether as a possible replacement for mesmerism or “animal magnetism.” Unfortunately, 19th century publication schedules prevented the editors from incorporating any details from Abbott’s surgery the previous day.

Scientific American 2, no. 4 (Oct. 17, 1846) (Linda Hall Library)

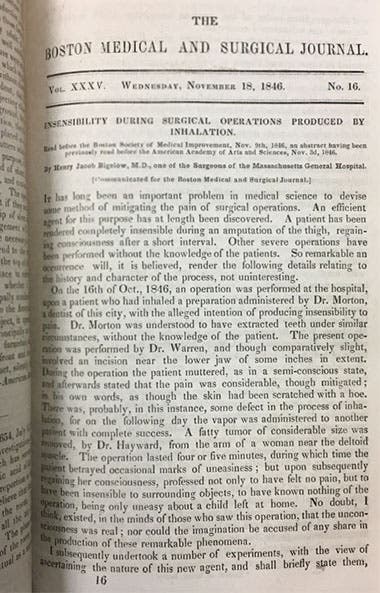

Henry Jacob Bigelow, a surgeon at Massachusetts General whose father Jacob was a prominent physician in his own right, wrote a more detailed account of Ether Day, and the surgeries it subsequently inspired, for the November 18, 1846 issue of The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, a precursor to the modern New England Journal of Medicine (fifth image). This journal is among the many publications, images, and artifacts related to the history of anesthesiology in the collections of the Clendening History of Medicine Library at the University of Kansas Medical Center. (Special thanks to librarian Dawn McInnis for making these materials available while researching this story.)

The first page of Henry Jacob Bigelow’s article, “Insensibility During Surgical Operations Produced by Inhalation,” in The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Nov. 18, 1846 (Clendening History of Medicine Library)

By the end of the 19th century, artists had begun commemorating the introduction of anesthesia as one of history’s greatest medical breakthroughs. In 1868, Boston’s municipal government authorized the creation of a monument honoring the development of ether anesthesia in the city’s Public Garden (sixth image). Later, portrait artist Robert Hinckley spent over a decade recreating Ether Day in his painting, First Operation Under Ether, which is currently on display at Harvard University’s Countway Library of Medicine. (first image)

Of course, the best place to celebrate Ether Day is at Massachusetts General Hospital. The Ether Dome is still accessible to the public, though it now serves as a lecture hall rather than an operating theater. Among the fixtures on display are a teaching skeleton from the 1840s, a replica of the Apollo Belvedere (an ancient Roman sculpture), and an Egyptian mummy sometimes referred to as “the hospital’s oldest patient” (seventh image).

Regular readers of this feature will note that it is somewhat unusual to designate a location, such as the Ether Dome, as a Scientist of the Day rather than an individual. Given the large number of people involved in the development of anesthesia and the historical significance of the Ether Day surgery, this exception feels justified. It also leaves the door open for us to explore the lives of several key contributors to the history of anesthesiology in future posts.

Benjamin Gross, Vice President for Research and Scholarship, Linda Hall Library. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to grossb@lindahall.org.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)