Scientist of the Day - Ernst Haeckel

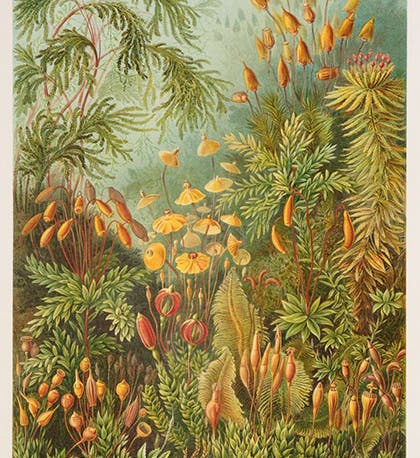

A variety of bryophytes or mosses, chromolithograph, in Kunstformen der Natur, by Ernst Haeckel, plate 72, 1899-1904 (Linda Hall Library)

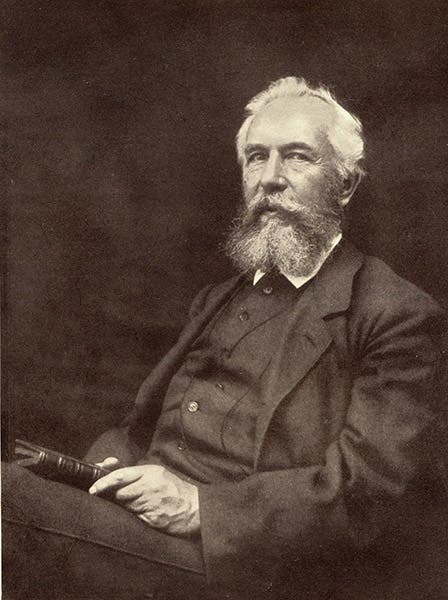

Ernst Haeckel, a German biologist and anatomist, died Aug. 9, 1919, at age 85. Haeckel was only 26 years old when he read the German translation of Charles Darwin's Origin of Species; he almost immediately adopted the theory of evolution by natural selection, and proceeded to become, within 10 years, the foremost advocate in Germany of evolutionary biology. He soon brought humans into the evolutionary story and published a remarkable tree diagram – the first evolutionary tree diagram – that showed humans, as well as the four great apes, radiating from a branch labelled "Anthropoiden." We discussed all this, in more detail, in an earlier post on Haeckel, where you may see his complete evolutionary tree, as well as a detail of the human and prehuman branches.

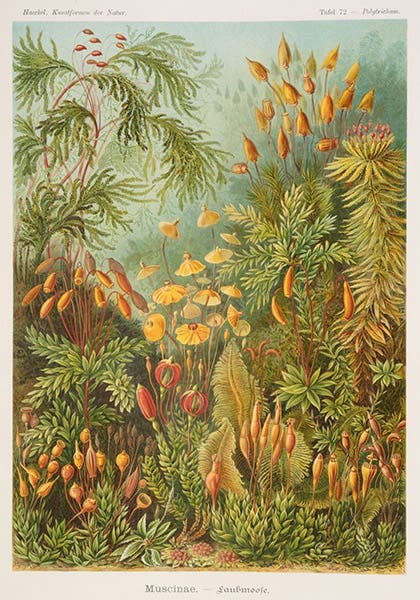

Today we will discuss the work for which Haeckel is best known, at least by the general public, since with it, Haeckel attempted to bridge the realms of art and nature. The book was called Kunstformen der Natur, Art-Forms of Nature, and it consists of 100 large lithographs, each showing a variety of living forms, arranged into intricate tableaux. Our first plate, as an initial example, depicts a forest of bryophytes, or mosses. The second one (third image), a more typical plate, shows ten fossil ammonites, crammed onto but carefully arranged to fill the page.

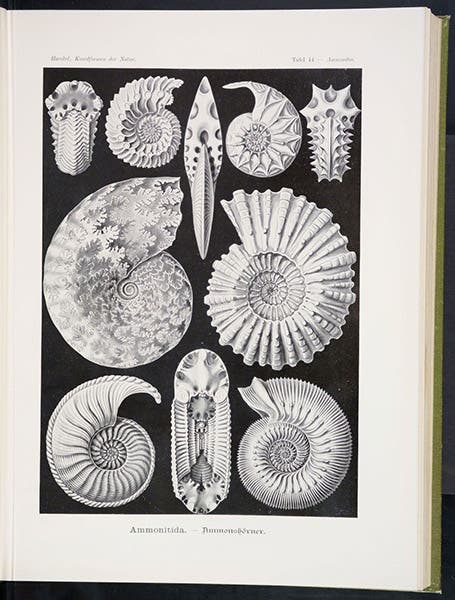

Various ammonites, lithograph, in Kunstformen der Natur, by Ernst Haeckel, plate 44, 1899-1904 (Linda Hall Library)

The plates were issued as a series of fascicles, with ten plates in each fascicle, between 1899 and 1904. The ten plates would usually include five or six plates of invertebrates, especially radiolaria and medusae (Haeckel’s specialties), plus some chosen from the classes of birds, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, or the plant kingdom. There were usually two pages of text for each plate, which, if we include the blank versos on each plate, made a substantial packet of 40 pages.

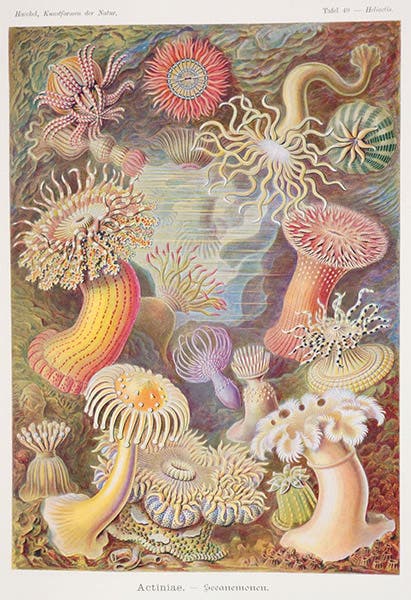

Sea anemones, chromolithograph, in Kunstformen der Natur, by Ernst Haeckel, plate 49, 1899-1904 (Linda Hall Library)

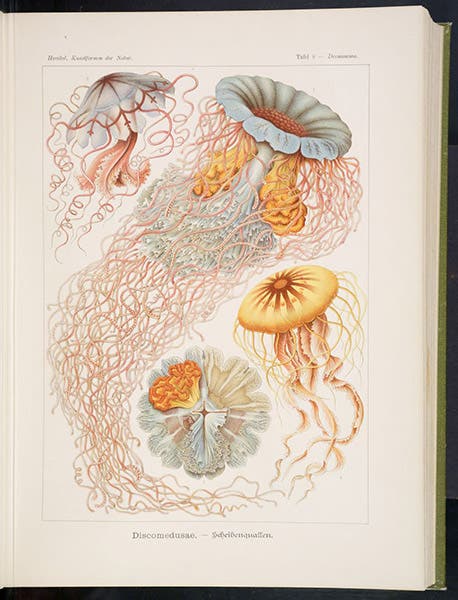

Our second group of plates shows a cluster of sea anemones (fourth image), and several medusae (fifth image). This latter plate is often reproduced, because not only is it beautiful, but the jellyfish on the central diagonal was named by Haeckel Desmonema annasethe, after his first wife, Anna Sethe, who died young.

Several medusae, including Desmonema annasethe (center diagonal), named after Haeckel’s deceased first wife, Anna Sethe, chromolithograph, in Kunstformen der Natur, by Ernst Haeckel, plate 8, 1899-1904 (Linda Hall Library)

It is said that Haeckel would make the initial sketches of the organisms himself, turn them over to the lithographer, who would make a draft for a plate, which Haeckel himself would then rearrange until he was happy with the overall design. It is the design which most people find so attractive, since the plates are so artful and exemplify the title so well.

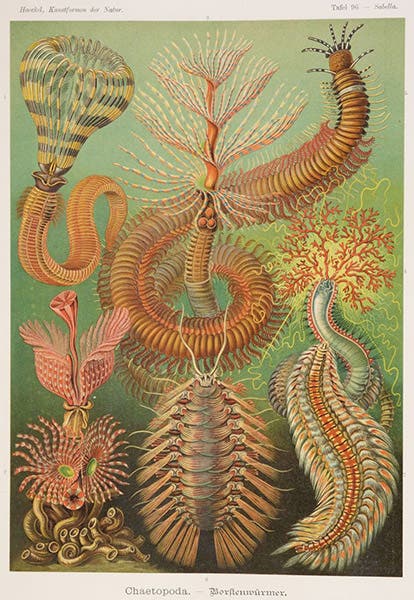

Fan worms, chromolithograph, in Kunstformen der Natur, by Ernst Haeckel, plate 96, 1899-1904 (Linda Hall Library)

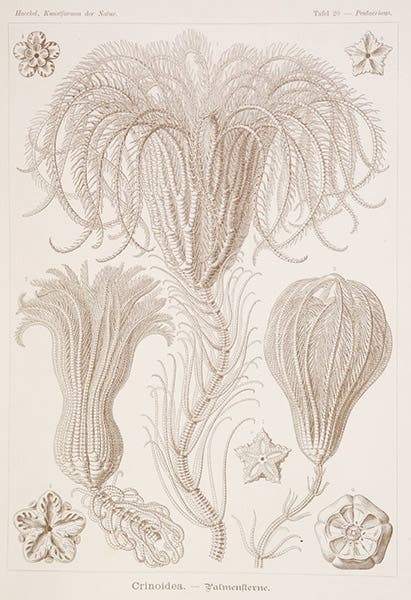

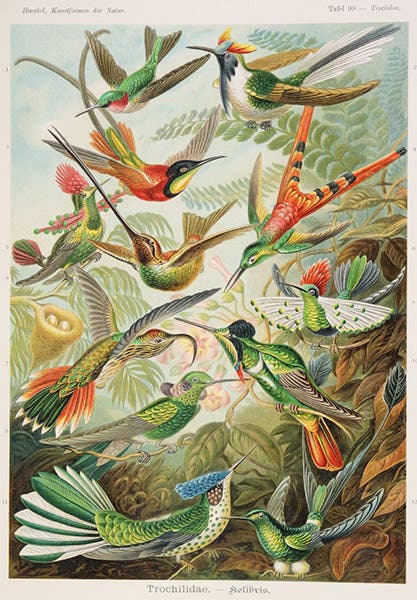

You will note that some of the plates are printed in black and white, some are tinted a single color, and some are full-color chromolithographs. This provides much needed variety, because ten full-color plates in a row, no matter how beautiful, would begin to weary the eyes. In choosing plates for this post, I selected a few of each kind. The hardest part of writing this essay was deciding which plates to leave out. Fortunately, our set has been scanned, so you may leaf through it online, if you have the time, to see what you have missed.

Crinoids, tinted lithograph, in Kunstformen der Natur, by Ernst Haeckel, plate 20, 1899-1904 (Linda Hall Library)

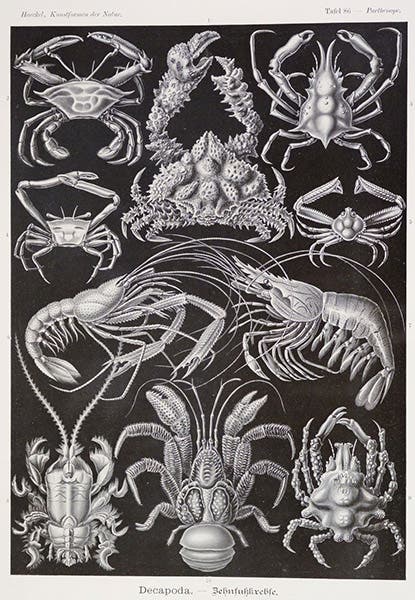

Our final set of selected plates show: fan worms (sixth image), crinoids (seventh image), decapods (shrimp and crabs, eighth image), and a variety of hummingbirds (ninth image).

Decapods, lithograph, in Kunstformen der Natur, by Ernst Haeckel, plate 86, 1899-1904 (Linda Hall Library)

A great deal has been made of the influence that Kunstformen der Natur had or might have had on early 20th-century art movements, such as Art Nouveau. That is outside my expertise. But I do think that the message of the book should not be overblown. Haeckel was really just trying to show that Nature is beautiful when seen as Nature arranges herself, but Nature is also beautiful when humans impose their own order, as Haeckel tried to do with the layouts of his plates.

Hummingbirds, chromolithograph, in Kunstformen der Natur, by Ernst Haeckel, plate 99, 1899-1904 (Linda Hall Library)

We have in the library a lovely large folio, Visions of Nature: The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel , by Olaf Breidbach (Prestel, 2006), that discusses the images in all of Haeckel’s books, including Kunstformen der Natur, and which also offers reproductions of some of Haeckel’s original sketches and drawings, from which the plates were made for his books. It requires, however, a sturdy lap-desk, if you wish to read it comfortably.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.