Scientist of the Day - Ernest Rutherford

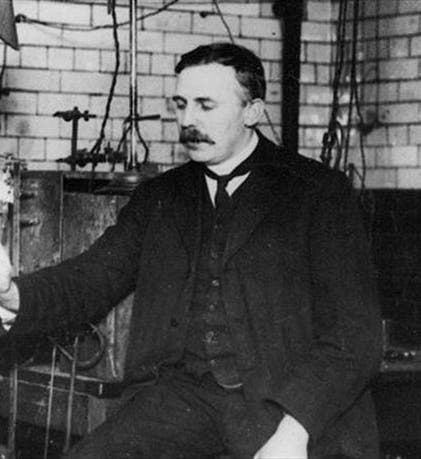

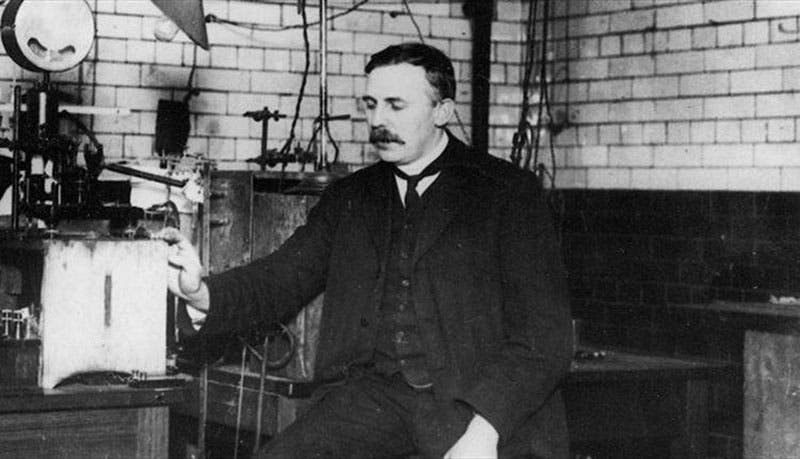

Ernest Rutherford, a New Zealand physicist working in Canada and England, was born Aug. 30, 1871. Rutherford came to Cambridge, England, on a scholarship in 1895. It was a heady time to be entering the world of physics, as the entire field was being turned upside down. X-rays were first detected by Wilhelm Roentgen in 1895, then radioactivity in uranium was discovered by Henri Becquerel in 1896, then J. J. Thomson (Rutherford's mentor at Cambridge), discovered the electron, and in 1898, Marie Curie and Pierre Curie discovered a new element, radium, that is radioactive as well. Rutherford jumped eagerly into these new fields of physical inquiry, and it was he who named the byproducts of radioactivity – alpha, beta, and gamma rays – and who first realized that when an element gives off one of these particles or rays, it transmutes into another element.

We discussed some of this in an earlier post on Rutherford, in which we also looked at his next great achievement: the discovery that the atom has a nucleus of positive charge, which comprises most of the mass of the atom. This came in 1911, when Rutherford had moved from McGill University in Montreal to the University of Manchester, and after he had discovered how to probe the atom with alpha particles, emitted by radium. His announcement of the nuclear atom was published in the London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine in 1911. You can read more about these experiments in our first post.

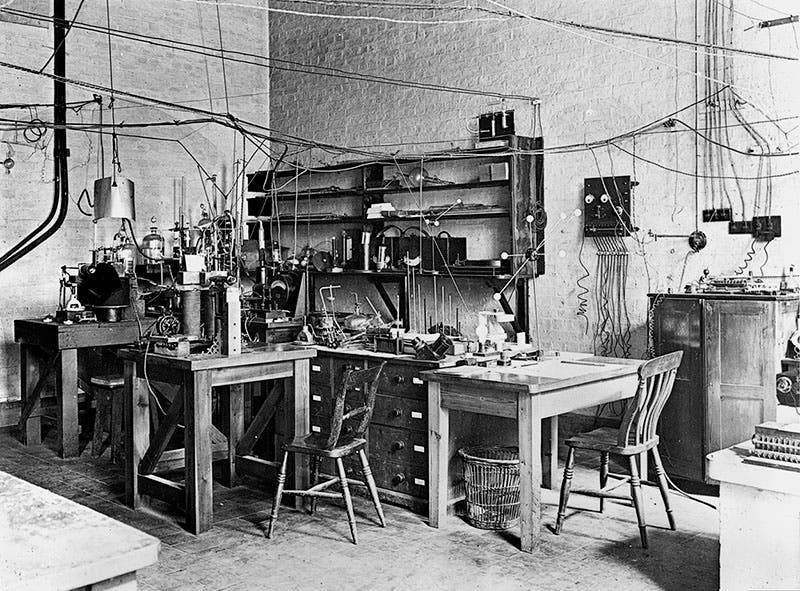

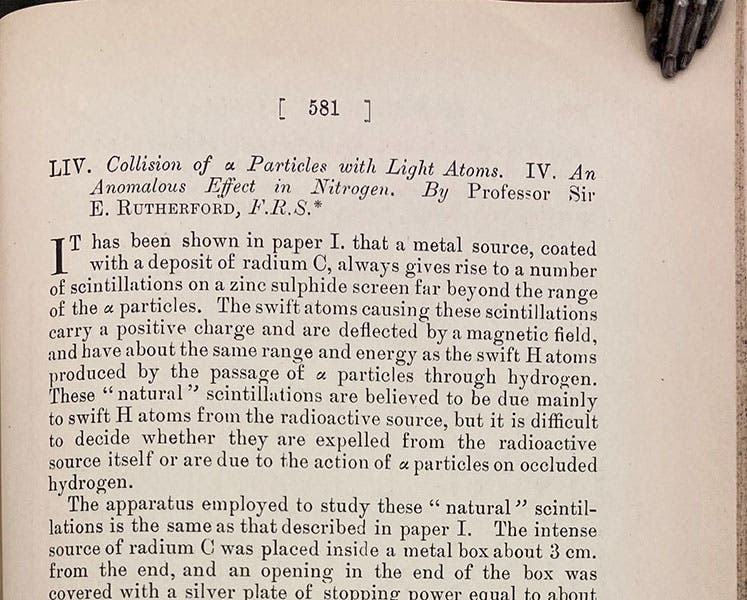

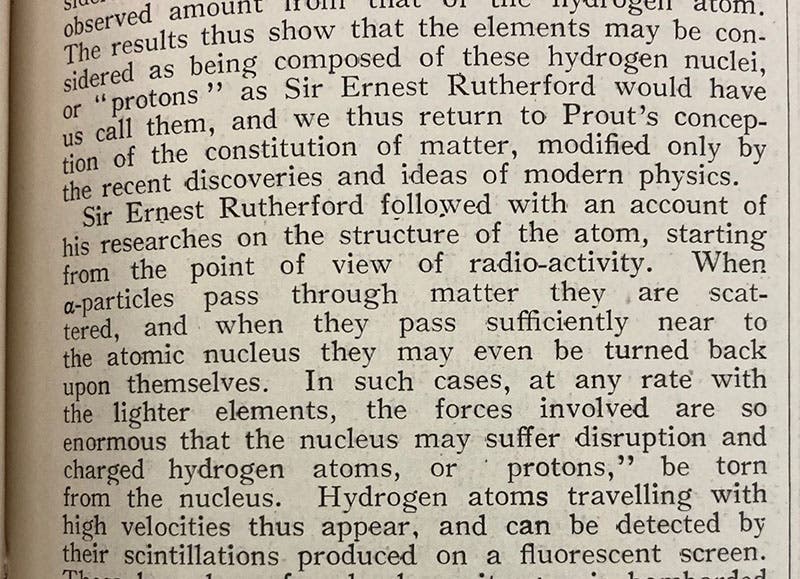

But there is more to the Rutherford story, and we pick up today where we left off. Rutherford continued to experiment with his alpha particle probes (which Rutherford had shown were actually fast-moving helium atoms, stripped of their electrons. His work was interrupted by World War I, but in 1917, he was able to resume his investigations in Manchester. He bombarded ordinary air with alpha particles and found that some sort of atomic or nuclear reaction occurred that could be picked up by his detectors. The only detectors then available were scintillation screens, which would emit a dot of light when struck by a charged particle. Rutherford soon realized that the charged particles were coming from the nitrogen in the air, and he then discovered that the particles being given off in the alpha particle-nitrogen interaction were positively charged, much more massive than electrons, but less massive than alpha particles. He concluded that they were hydrogen atoms, without their electrons, and he surmised that the alpha particles were smashing nitrogen atoms into their constituent parts, suggesting that all the elements were built up from hydrogen atoms. He published his conclusions in 1919 in the London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine (see detail, fourth image), and the next year, 1920, he coined the word proton to use instead of hydrogen atom for the positively charged particle that was knocked free in these interactions. At least one researcher believes that the first appearance of the word proton in print is in a Nature editorial of 1920 summarizing Rutherford’s nitrogen experiments; since I have never seen it reproduced before, I show it to you here (fifth image).

It is often said, especially in the older literature, that Rutherford discovered that when at atom of nitrogen is struck by an alpha particle and emits a proton, it transmutes into an isotope of oxygen. This is indeed what happens, but Rutherford did not realize that in 1919 – he had no way to do so, using only scintillation screens as detectors. The transmutation of nitrogen into oxygen would be discovered by his student, Patrick Blackett, in 1925, using the new cloud chamber invented by C.T.R. Wilson, which allowed one to distinguish negative and positive particles by the direction they curve. You can learn more at our post on Blackett and our post on Wilson.

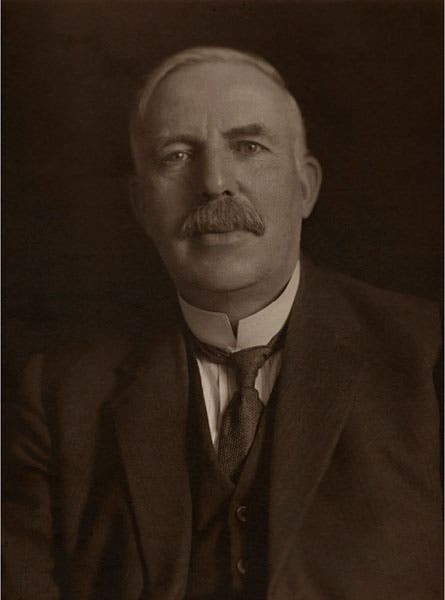

In the same year that his article on the proton was published, J.J. Thomson died, and Rutherford was appointed to succeed him as director of the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge. This last third of his career was as distinguished as the first two, only now he was directing and supervising brilliant young physicists, who were making the discoveries. As a measure of the greatness of the Cavendish Lab under Rutherford's directorship, it is often pointed out that in the year 1932, at the Cavendish Lab, James Chadwick discovered the neutron (which had been predicted by Rutherford in 1920), John Cockroft and Ernest T.S. Walton built the first particle accelerator, using protons as projectiles; and Blackett discovered the positive electron, or positron. Never before, or since, has one lab scored a triple coup like that in a single year. Rutherford deserves a great deal of the credit. He remained director of the Cavendish until his death on Oct. 19, 1937.

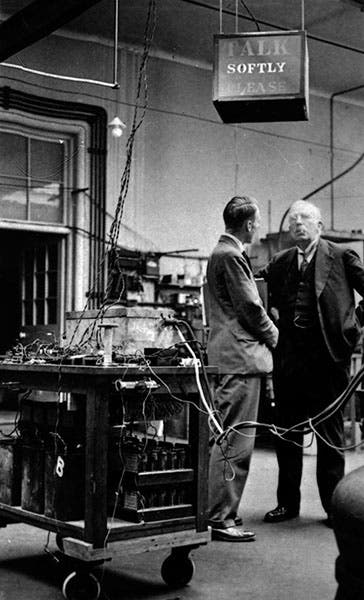

Rutherford was a tough director, apparently, and loud as well, so that a sign was installed in one of the labs to ask that sensitive measuring instruments not be disturbed; there is a famous photograph by Walter Andrews of 1934, showing Rutherford standing under the sign, looking ready to bellow (sixth image).

One of Rutherford’s most brilliant students, the Russian Pyotr Kapitsa, always referred to Rutherford as “the Crocodile,” because he was to be both feared and respected. When the Royal Society provided funds to construct a separate laboratory at the Cavendish to house Kapitsa’s high-energy magnets, Kapitsa had a crocodile carved into the brickwork outside the entrance, and we show two photos of the carved Crocodile, drawn from the website of the Cambridge University Physics Department (seventh and eighth images). I have never read anything about Rutherford’s reaction to the artwork.

As a footnote, I would like to repeat that Rutherford published his two most important papers, on the nuclear atom and the proton, in the London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine. We don't think of this journal as being in the same league with the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, or Nature, or Science, or Physical Review, but in the early 20th century, most of the significant papers on particle physics and atomic structure appeared in the Phil Mag, as it was affectionately called, not only Rutherford's two papers of 1911 and 1919, but J. J. Thomson's article announcing the discovery of the electron (1897), Niels Bohr's paper proposing the quantum atom (1913), and Henry Moseley's discovery of atomic number (1913). You could reconstruct much of the early history of atomic physics from its pages. We have a nearly complete run of this journal in the Library, going back to its founding issue of 1798.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.