Scientist of the Day - Elias Ashmole

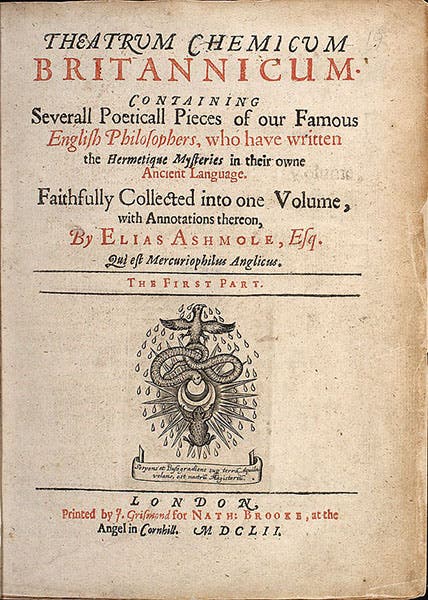

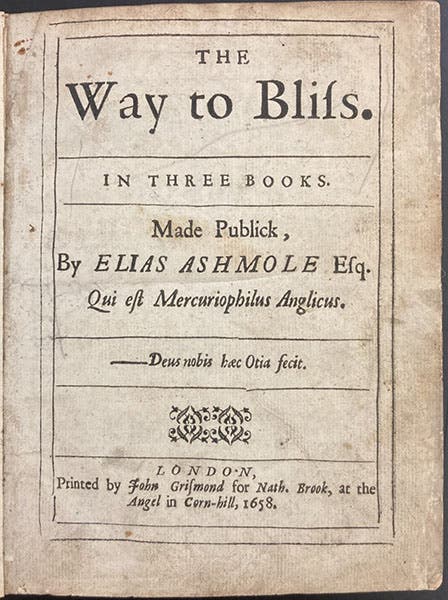

Elias Ashmole, an English collector of curiosities and manuscripts, was born May 23, 1617, in Lichfield, Staffordshire. Although he practiced as a lawyer in London, he acquired most of his wealth by marriage, and he used those funds to buy manuscripts, coins, and antiquities. Although he was not a practicing alchemist, he liked alchemical manuscripts, and in 1652, he published Theatrum chemicum britannicum, a collection of British manuscripts on alchemy from the 15th and 16th centuries, many never before published. We do not have this work in our collections, so we show the titlepage of a copy at the University of Pennsylvania (second image). But we do have Ashmole’s last alchemical publication, The Way to Bliss (1658), an alchemical manuscript from the previous century on the Philosopher’s Stone, that he found too late to include in the Theatrum (third image).

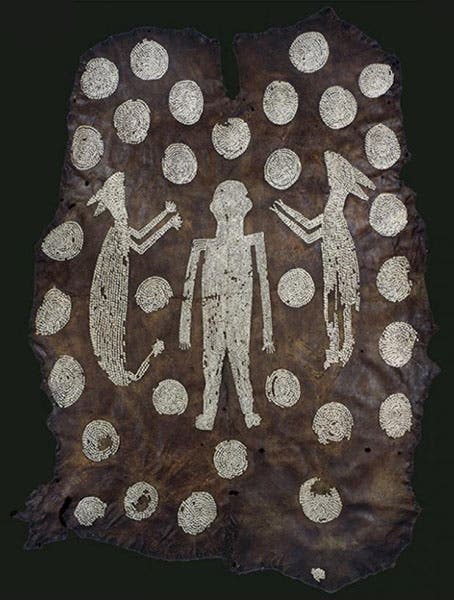

Around 1650, Ashmole met the gardener and collector John Tradescant the Younger. The younger Tradescant, as had been his father, was gardener to the king (Charles I), and the two Tradescants collected seeds and plants from all over the world, especially America, (where they were aided by John Smith) and proceeded to introduce those to England. They also collected curiosities and antiquities, such as the marvelous "Mantle of Powhatan," a shell-covered leather robe from the Chesapeake Bay region of Virginia (fourth image). These were displayed at their house and garden in Lambeth in London, and available for viewing by the public, leading some to call their house the oldest public museum in England. Ashmole helped Tradescant the Younger published a catalog of their collection, Musaeum Tradescantium (1656),which is also not present in our collections. Tradescant, in return, bequeathed his entire library and collection to Ashmole. When Tradescant the Younger died in 1662, Ashmole had to battle Tradescant's wife in the courts for a while, but he eventually took possession of Tradescant’s legacy, and between the two collections, Ashmole had the finest museum in England.

Perhaps impressed by the fact that the Tradescants opened their collections to the public, Ashmole, in 1677, offered both collections to Oxford University, provided they would construct a suitable building to house them. Oxford agreed, and in 1683, Ashmole’s bequest was moved into the new building, and the Ashmolean Museum opened its doors. It was the second university museum in Europe, and the first public one. The first Keeper was the antiquary Robert Plot, and he was succeeded in 1690 by the fossil collector Edward Lhuyd.

Ashmole has taken some flak for seeming to attempt to overshadow the Tradescants and present their collections as his own. And it is true, the bulk of the gift was the collection assembled by the Tradescants, not Ashmole. However, Ashmole had intended to provide many more objects and books from his own collection, but a disastrous fire in Middle Temple destroyed many of his books, coins, and manuscripts, and most of the surviving books were later transferred from the Ashmolean to the Bodleian Library. So he was not quite the self-aggrandizing scoundrel that Tradescant fans make him out to be.

The Ashmolean Museum, in 1894, moved on to larger quarters, and the original building, called the Old Ashmolean, has since 1924 housed the Museum for the History of Science at Oxford (fifth image). Up until Oxford built its own Museum of Natural History in the 1850s, the second floor of the Old Ashmolean was used for teaching, and the famous engraving of William Buckland lecturing on ammonites to his students gives us a view of the inside of the building (sixth image).

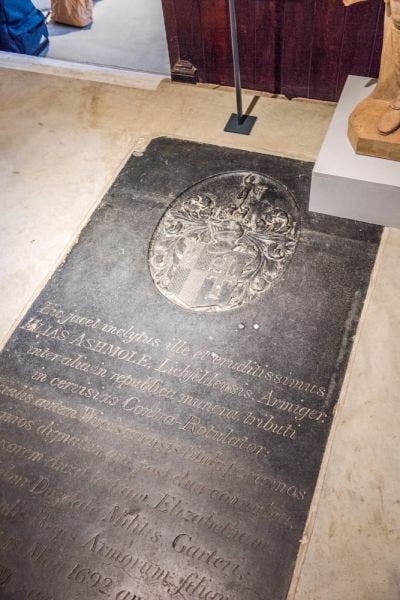

Ashmole died in 1692 and was buried in Saint Mary's Church at Lambeth, underneath an ornate slab, not too far from the Tradescants, who are in the churchyard outside. Saint Mary’s Church is now a museum, the Garden Museum. A portrait of Ashmole, by John Riley, was given to the Ashmolean in 1683 by Ashmole himself. A copy is in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

I was formerly under the impression that my favorite Ashmolean painting, The Hunt in the Forest, by Paolo Uccello, had been part of Ashmole’s bequest, but I was deluded; it was part of the Fox-Strangways collection and was given to the Ashmolean in 1850. But the Mantle of Powhatan, presented by Ashmole on behalf of the Tradescants, is still there (fourth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.