Scientist of the Day - Eleanor Glanville

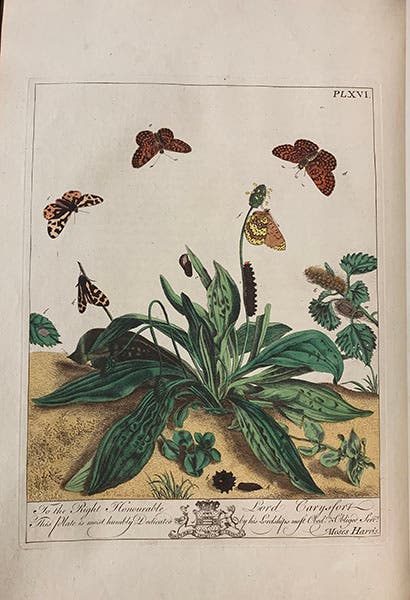

In honor of women’s history month, today’s scientist of the day is the English lepidopterologist, Eleanor Glanville (1655-1709). This gentlewoman collected some of the rarest British butterflies in the marshes and meadows of Somerset, England. Glanville’s observations are the earliest written records that survive of butterflies and moths in this wetland region. In her own lifetime, Glanville was known for her knowledge of British insects, but my recent research indicates that she collected specimens from abroad too. Today, her legacy survives in a butterfly still known as the Glanville Fritillary, or Melitaea cinxia. There is no surviving portrait of Glanville.

Tickenham Court Farm, Somerset, United Kingdom, photograph, 2022 (photo by the author)

Eleanor Glanville was born Eleanor Goodricke in 1655, to General William Goodricke and Eleanor Poyntz (nèe Davis). By age 11, both of Glanville’s parents had died, leaving her a vast estate in Somerset, just 10 miles outside of Bristol. The jewel of her holdings was Tickenham Court, an old Medieval structure with spare limestone walls and arch-braced ceilings (second image). In all, she inherited 1,300 acres, more than half of which were meadows and moorlands. These marshy wetlands fostered biodiversity and provided an ideal habitat for butterflies. Today, the region is known as the Somerset Levels. Growing up here may have encouraged in Glanville a kind of curiosity and interest in the natural world.

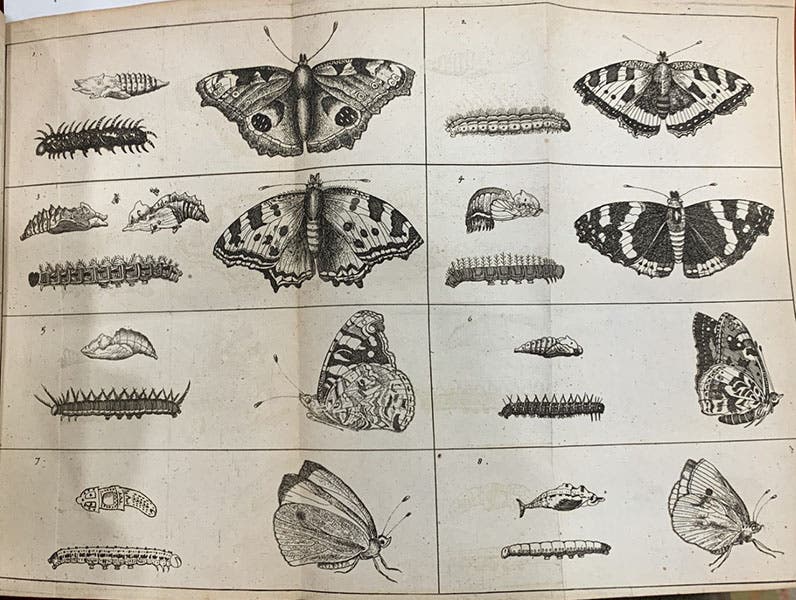

The earliest record of Glanville’s entomological activity dates to 1701, when her correspondent James Petiver, FRS, added one of her butterflies to his upcoming publication of Gazophylacii Naturae. Petiver was a well-known collector in his own day, and a close associate of Sir Hans Sloane. Evidence for the Glanville-Petiver correspondence is sparse, but they did maintain a friendship until at least 1704, when Petiver apprenticed Glanville’s youngest son to his apothecary shop on Aldersgate Street. Over these years, Glanville sent Petiver butterflies, caterpillars, moths, beetles, and mosses gathered from Somerset, Wales, and the Americas. Along with these shipments, she included her own observations on the life cycles of insects, making astute descriptions of the morphology of larval states. Glanville relied on printed illustrations to aid her descriptions, including Martin Lister’s 1682 English translation of Johannes Goedaert’s Of Insects. Lister had new plates engraved for his translations, reorganizing the insects into neat tables. Linda Hall Library has a copy of Lister’s Latin translation, with the same plates as the English one that Glanville used (third image).

Glanville belonged to a circle of naturalists on the fringes of the Royal Society that included the apothecary-collector James Petiver, the silk designer Joseph Dandridge, the Reverend Adam Buddle, and the Cambridge naturalist William Vernon. She often visited London and kept an apartment there to display her specimens. Vernon once wrote of a visit to Glanville’s, “a lady came to town with the noblest collection of butterflyes, all English, which has sham’d us."

Battus philenor, the Pipevine Swallowtail, specimen sent by Eleanor Glanville to James Petiver, ca 1700, preserved with mica and paper, Glanville name in ink on label; James Petiver Historical Entomology Collection, Natural History Museum of London, c. 1700 (photo by the author)

Remarkably, approximately 8 of Glanville’s butterflies and moths still survive to this day as part of the Petiver Historical Entomology Collection of insects at the Natural History Museum of London. Petiver had a unique way of preserving specimens: he created small envelopes out of mica sheets and paper strips. He often labelled these envelopes with reference to his own catalogues and whoever sent him the specimen. We see here Battus philenor, the Pipevine Swallowtail, sent by Glanville to Petiver around 1700 (fourth image). Petiver died in 1718 and Sir Hans Sloane purchased his diverse collections from Petiver’s relatives. Nearly twenty years after this purchase, Sloane’s curators undertook the task of reorganizing Petiver’s collection of butterflies into two large, bound folio volumes. Upon Sloane’s death, he bequeathed his collections to the British nation, effectively founding the British Museum, the first national museum of its kind. Glanville’s specimens, though small in number, belong to this history of the public museum.

Glanville died in 1709 in London. She had disinherited her four surviving children and left her estate to a distant cousin in Yorkshire. Glanville’s eldest son, Forest Ashfield, attempted to overturn her will on the grounds of insanity, in part because his mother collected butterflies. After a lengthy court battle, Forest won the title to his mother’s estate and eventually sold off all the land.

The story of Glanville’s alleged madness passed down through subsequent generations of entomologists, eventually taking on the quality of legend. Nearly 50 years after Glanville’s death, the artist and entomologist Moses Harris included depictions of the Glanville Fritillary in his 1766 book on butterflies, The Aurelian (first and fifth images), and then mentioned the trial:

Lady Glanvil, whose Memory had like to have suffered for her Curiosity. Some Relations that was disappointed by her Will attempted to set it aside by Acts of Lunacy, for they suggested that none but those who were deprived of their senses, would go in Pursuit of Butterflies.

Harris claimed that the great naturalist John Ray rode out to Exeter to testify to Glanville’s “laudable Inquiry into the the Wonderful Works of the Creation” and that his testimony saved the day. This is an impossibility, however, because John Ray had already been dead four years by the time of the trial. Nevertheless, this blend of fact and fiction made Glanville a legend amongst entomologists, who shared stories of the days of yore when entomologists were a misunderstood bunch of bug chasers.

Michele D. Pflug is a current research fellow at Linda Hall Library and a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of Oregon. Her dissertation retells the life and legacy of Eleanor Glanville to shed light on women in natural history in the early eighteenth century. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to mpflug@uoregon.edu.