Scientist of the Day - Edward Lear

Edward Lear, an English nature artist and poet, was born May 12, 1812. From 1830 through 1846, Lear made his living (poor though it was) painting birds and then animals for various publications, including one of his own, before he published his book of nonsense verse in 1846, began a series of extensive travels and travel narratives, and sent his life off in a new direction. He provided 68 plates for John and Elizabeth Gould's Birds of Europe (1832-37), and they are in my opinion the finest bird illustrations in the entire set of five volumes. I wrote a post on Lear some years ago, in which we showed some of those plates, and you might want to look at them – the lithograph of Great Heron he did for Gould is simply magnificent. Here is a larger version, as it appeared in our 2009 exhibition, The Grandeur of Life.

We mentioned in our first post that we once "owned", or at least had in our vault, the one Lear bird work that he tried to publish himself, the folio-sized Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots (1832), with 42 lithographed plates of parrots, macaws, lories, and the like. Unfortunately, our copy was only on loan, and when the couple who owned it divorced, Lear's Parrots became part of the settlement and left our vault, never to return. The Illustrations of Parrots, which should have been a splendid accomplishment, instead brought Lear financial grief. He had a problem with some of his subscribers not coming through with payment, and he was still broke and in debt in 1834 after fulfilling all the subscriptions, and had 50 sets of prints on his hands with no buyers, so he sold these (and their reproduction rights) to John Gould, who was able to find buyers, and the £50 he paid Lear (£1 per set of 42 plates!) put him back in the black.

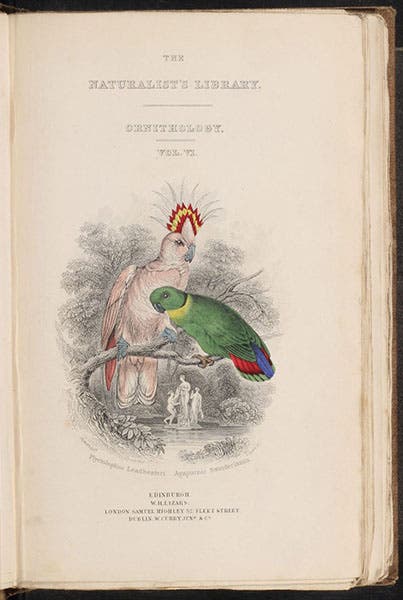

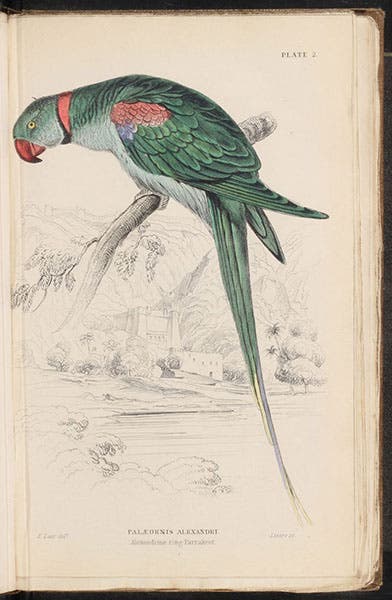

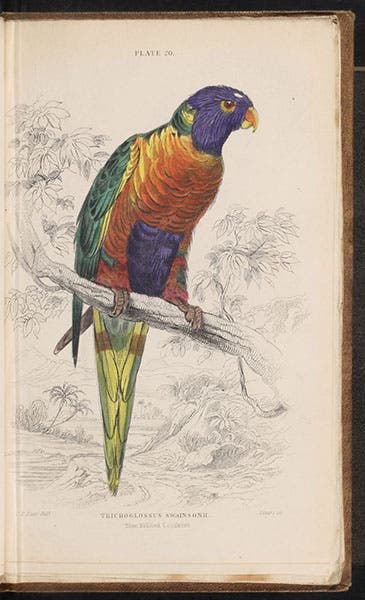

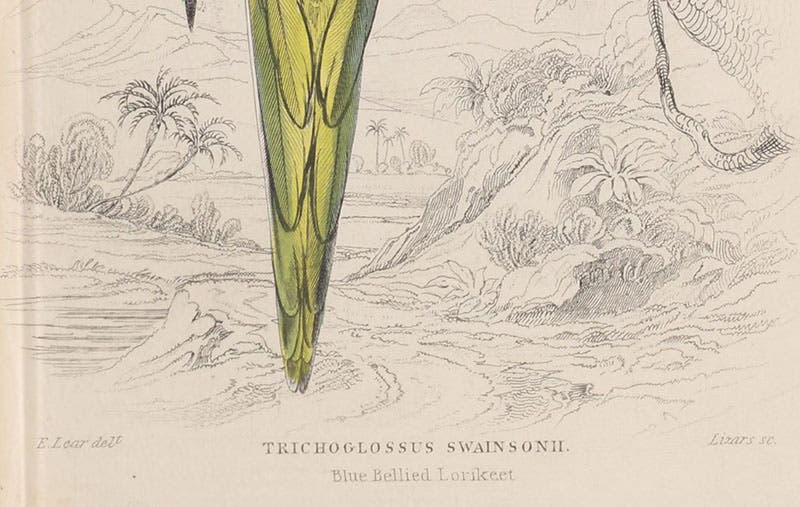

When, the next year, William Jardine came calling, asking Lear to illustrate a volume on parrots being written by Prideaux John Selby for Jardine’s Naturalist’s Library series, Lear was eager to do so, since he already had 42 paintings he could reduce for the octavo publication, until he realized that he no longer had the rights to those images. So he came up with 30 new ones. And while our library can no longer bring out the folio Illustrations of Parrots, we still have Selby's small Natural History of Parrots (1836), with its 30 Lear drawings, engraved by William Lizars (who engraved the first 10 plates for Audubon’s Birds of America) and then hand colored. It is a beautiful little book.

If you compare Selby’s Parrots of 1836 with Lear’s 1832 folio volume, the Selby work is not that impressive – after all, the plates are only one-twelfth the size of those in the larger work. But if you look at it by itself – or better yet, enlarge some of the plates, as we have done here – then they have a grandeur belied by their small size. It helps that the coloring, supervised by Lear, was exceptionally well done. The five plates we show here, either in full or in detail, happen to be my favorites, but I had to leave out some exceptional drawings, which you can find for yourself, if you so desire, in our online copy of Selby’s book.

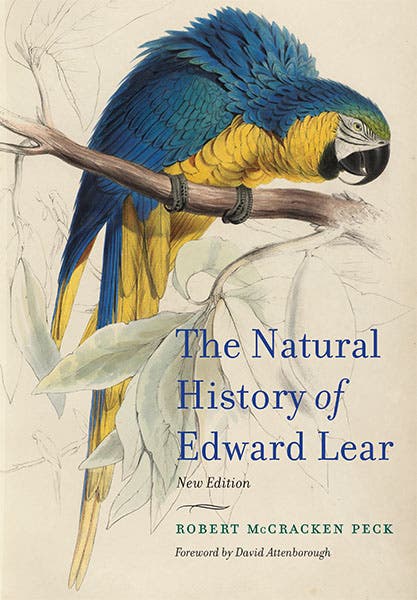

Many of Lear’s watercolors and studies for his large Illustrations of Parrots are in the Houghton Library at Harvard, and in 2012, they mounted an exhibition commemorating the 200th anniversary of Lear’s birth and put some of Lear’s artwork on display. For the occasion, my friend Robert McCracken Peck at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, who was a guest curator of the exhibition, wrote an essay on Lear for the Harvard Library Bulletin that included extensive discussion of both versions of Lear’s parrots, and we have based our discussion here on that essay. You can access his essay at this portal. Dr. Peck subsequently expanded his essay into a book, The Natural History of Edward Lear (2016), with a second edition in 2021, which you might enjoy. We show the cover of the second edition, since it presents yet another Lear parrot, this time a large Blue-and-yellow Macaw (ninth image).

Front cover of The Natural History of Edward Lear, by Robert McCracken Peck, new ed., Princeton Univ. Press, 2021 (photo courtesy of the author)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.